As the impacts of COVID-19 play out across the region, countries are frantically trying to prepare policy responses to a highly intertwined set of health, economic, social and political crises. Aid programs too are having to rapidly adjust to ensure they remain relevant to the new and evolving set of development problems faced by partner countries; and make an effective and efficient contribution to addressing these problems under the social distancing constraints posed by COVID-19. In this post, Cardno outlines the framework we are applying to guide this ongoing re-calibration or ‘pivot’ process on programs across our portfolio. The framework reflects adaptive management principles, and emphasises the need to anticipate likely phases of the pandemic, and to plan/sequence program responses accordingly.

The COVID-19 program cycle

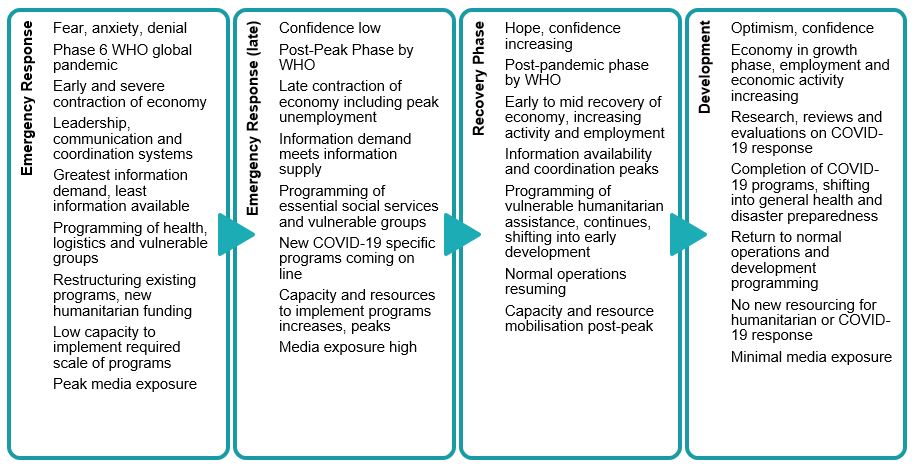

COVID-19 modelling, as well as lessons from previous pandemics and disasters, suggests predictable (though highly non-linear) phases of the COVID-19 crisis and its impacts. The first phase is 6–18 months of significant upheaval (aligned with the average time for pandemics and health responses), followed by a further 2–3 years for the early recovery process (aligned with the average time of a global recession). This in turn suggests a likely sequencing of program responses to the crisis – as depicted below.

The cycle builds on basic humanitarian concepts such as emergency, recovery and development, and underscores the importance of projecting responses that bridge the humanitarian and recovery phases and beyond. While the cycle implies a linear relationship, the reality is that health and economic crises typically demonstrate significant spatial and temporal variation. Some countries and regions will be affected earlier, have higher peaks, have multiple peaks, or not even have the testing capacity to produce reliable data. And even the smoothed-out curves we see in the daily newspapers are often misleading, because countries and particularly sub-national areas, are likely to have flare-ups and hot-spots for years to come. Despite all this texture, history does however show one thing: we are in the midst of an exponential crisis now; technology and policy responses will be likely factors that get us over the peak (particularly social distancing and improved testing and assessment regimes); and we will eventually move towards recovery and development at different time frames.

A process for your pivot strategy

Programs are currently having a dialogue between donors, implementers, partners and others to design a pivot strategy that anticipates and plans for the various phases of the COVID-19 program cycle. Programming decisions must be cognisant of priorities and trade-offs within a broader national response in highly constrained circumstances; while responses must be cognisant of potential impacts on the most vulnerable.

We suggest four crucial steps to developing a pivot strategy.

Step 1: Know your context. This should particularly look at the anatomy of anticipated impacts, including health (e.g. health system coping capacity), economic (e.g. impact on remittances or specific sectors), social (e.g. impact on domestic violence or social cohesion), and political (e.g. changes in rule of law or electoral systems). Where possible, stratify this at sub-national levels and by factors of social exclusion (e.g. women, people with disability, caste, religion, socio-economic), as COVID-19’s impacts will not be uniform.

Step 2: Define critical problems. Building on the above, explain how problems in your sector of interest may exacerbate the impact of COVID-19, and in turn, how COVID-19 may exacerbate existing problems in your sector. Refer back to the COVID-19 program cycle and think about the timeframes associated with the phases.

Step 3: Define your investment decision-making criteria. There are three factors at the heart of this for COVID-19:

- Is the investment still relevant to the communities you are working with (i.e. does it address the critical problems)?

- Are you actually able to deliver it considering the social distancing that may persist?

- Are you still able to demonstrate value for money?

Step 4: Use DAKI to review all activities and operations.

- Drop – what is no longer relevant or possible to implement cost-effectively? E.g. general investments no longer relevant to the new context.

- Add – what new activities would complement current activities? E.g. humanitarian responses, health infrastructure and communications, governance technical assistance for early recovery.

- Keep – what can you keep doing without changes? E.g. social protection, gender-based violence and WASH programming.

- Improve – what changes do you need to make (programmatic and operationally)? E.g. increased emphasis on early recovery support and inclusion programming.

A final word

Similar processes have been used for many years to support agile programming in dynamic contexts, providing a framework to assist with strategic decision-making. When applying it to COVID-19, it is important to engage widely and frequently update your pivot strategy as new information comes to light. Programs, organisations and partnerships tend to have core competencies based on a history in sectors or geographic areas, and while it’s important to pivot, it’s also important to maintain a long-term perspective.

The blog draws on the work of the Cardno Development Effectiveness Unit, led by Dr David Carpenter.

This post is part of the #COVID-19 and international development series.