Anti-corruption conferences usually don’t resonate with the broader public. Even high-level meetings often fail to get much traction. But the upcoming 16th International Anti-Corruption Conference (IACC), which is to be held in Putrajaha, Malaysia on 2-4 September, has caused a media sensation, even before the early-bird ticket price for the event expired. Indeed, on social media, and in activist and political circles, critics were calling for its cancellation. Why? Well, the kerfuffle was all to do with one man: Najib Razak, the Prime Minister of Malaysia.

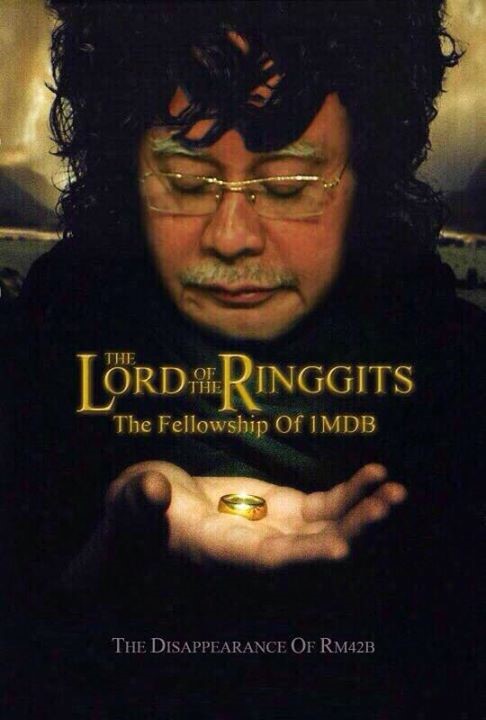

Mr Najib was touted to headline the event and provide the opening address. But in June and July, he was featured in the Wall Street Journal for allegedly playing a key role in a long-running corruption scandal. The WSJ reported that government investment fund, 1Malaysia Development Bhd. (1MDB), channelled US$700 million into Mr Najib’s personal bank account. While the Prime Minister denied any wrongdoing, the WSJ later released flowcharts and bank documents [pdf] that show funds being directed into the PM’s account. The WSJ also detailed how the fund had been used to indirectly help Mr Najib’s 2013 election campaign. The economic and political fallout has been immense, the value of the Ringgit fell and Malaysia’s opposition has had a field day. Opposition parties had been calling for Mr Najib’s resignation over the scandal for some time; the WSJ’s exposé only strengthened their hand.

Obviously the allegations were not a good look for the IACC. Having a speaker accused of such flagrant corruption introduce one of the world’s largest anti-corruption conferences would have been acutely ironic. Particularly when the theme of the conference is: Ending Impunity: People. Integrity. Action.

Shortly after the WSJ’s June exposé linking the 1MBD fund to electioneering, the IACC posted a blog on its website explaining that Transparency International Malaysia and others involved with the event were submitting four complaints to the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission. But the Malaysian PM was still featured as the keynote speaker.

Following the WSJ’s July article and release of bank documents, the PM was still the featured headliner. On 3 August the IACC released a statement on the scandal and outlined changes needed to improve the country’s anti-corruption capacity. But there was no change of headline speaker. Sometime between 13 and 24 August the organisers finally dropped the PM from the schedule. This was done quietly. There was no press release, no blog, and, from what I can see, no tweets. Reference to the PM just disappeared from the website.

In dropping the PM the organisers dodged a bullet. Many Malaysians were incredulous that the IACC would provide a platform for the PM. They voiced their frustrations on social media. The opposition called for the event’s cancellation, with one leader suggesting that the conference would bring further shame to the country. Of course, the opposition used the event to highlight the need for a new government, with Democratic Action Party leader, Lim Kit Siang, rhetorically asking if the event would “present a live example as to how difficult or even impossible it is in a country like ours to end impunity for corruption, unless there is a total change of government?”

This episode highlights the international anti-corruption sector’s biggest blind spot: political engagement. One of the key organisers of the event, Transparency International, stresses that it is not politically aligned. Yet by allowing a platform for prominent politicians, events like these are steeped in politics. They can legitimise governments’ anti-corruption credentials while papering over their corruption and other abuses of power.

At the 14th IACC in Bangkok I watched as Hillary Clinton espoused the virtues of “honest government”, even though she may have been violating federal transparency regulations by routing her official correspondence through her private email. And the then Thai prime minister was happy to use the event to highlight his government’s anti-corruption credentials (although acknowledging the problem of corruption), shortly after his government cracked down on protesters, resulting in the killing of more than 80 civilians.

The IACC aims to bring together heads of state, civil society and the private sector to talk about ways of tackling corruption. This is laudable. But perhaps it is time to stop featuring high-level politicians, and focus on the hard-working activists and anti-corruption bureaucrats behind the scenes. When I attended the IACC conference in 2010, I was fascinated by the diverse work of anti-corruption groups in attendance. The politicians didn’t add much other than overly scripted platitudes.

Highlighting those on the front lines is likely to result in less press coverage and fewer ticket sales. But it could ensure that the issues facing those tasked with implementing anti-corruption reform can network and discuss strategies away from their political masters. To attract more activists and bureaucrats the conference would first need to reduce ticket prices. At 350 Euros (AU$565) for NGOs, academics and students (even more for others and those who register late), the early-bird price is hefty.

If the IACC continues to feature prominent politicians, the case of Malaysia’s disappearing PM should jolt organisers into thinking through the broader implications of giving politicians air time. The upcoming conference will feature ‘game changer’ sessions, which will highlight how technology, journalists and social entrepreneurs might improve anti-corruption campaigns. Perhaps the next conference could focus on political game changers, and examine the ways that anti-corruption actors themselves shape and are shaped by politics. Acknowledging that anti-corruption advocacy has political ramifications – even if they are unintended – would be a good start.

I’m a fan of the IACCs and I’d be happy to attend the next one. Hopefully I’ll see fewer political elites and more activists taking centre stage.

Grant Walton is a Research Fellow with the Development Policy Centre and Deputy Director (International Development) for the Transnational Research Institute on Corruption.

Very useful and informative post, thank you.