For months, New Caledonia has been wracked by conflict between the independence movement and French security forces. A key trigger for the crisis was a vote in the French National Assembly on 13 May, as President Emmanual Macron sought a constitutional amendment that would add an estimated 25,800 people to voting rolls for New Caledonia’s three provincial assemblies and national Congress.

The debate over New Caledonian voting rights is impacted by broader demographic trends, especially with the emigration of thousands of French nationals over the last decade.

In line with other Pacific island nations, New Caledonia has seen significant shifts in migration and labour mobility.

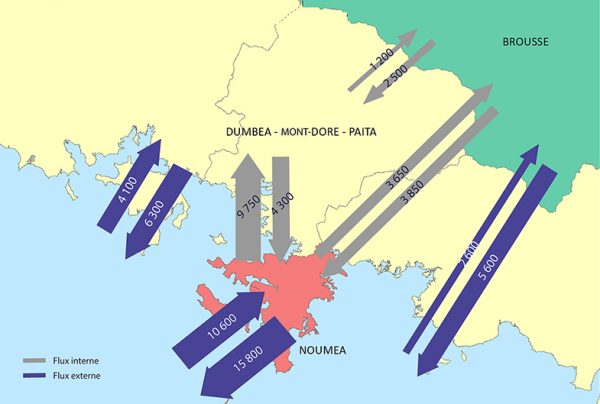

In recent decades, many indigenous Kanak have migrated to the capital Noumea from “la brousse” (the rural areas and outlying Loyalty Islands). As the population of New Caledonia’s Southern Province has grown, some Noumeans have also relocated from the centre of the capital to peri-urban housing estates and surrounding towns (Dumbea, Paita and Mont Dore) — see Figure 1. Despite improved opportunities for education, employment and enjoyment in the capital, the startling inequalities between rich and poor and the poverty of urban life were key drivers of the riots after 13 May, which initially focussed on greater Noumea.

Figure 1: Migratory flows between Noumea, its surrounding municipalities, the rest of New Caledonia and the outside world

Source: Recensement de la population 2019 – Nouvelle-Calédonie (Synthèse N° 45 – ISEE-NC).

Less attention has been paid to a third but more significant change. For more than a decade, tens of thousands of French nationals have left the Pacific dependency. In the last five years, New Caledonia’s total population has actually begun to shrink.

New Caledonia has always been a colony of settlement and migration, in contrast to French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna. After its early role as a prison, free settlers were transported in the late 19th century onto stolen Kanak land. The arrival of indentured labour from Asia and Oceania in the early 20th century, to work as miners in the burgeoning nickel industry, added new communities. Decades later, New Caledonia saw a population spike during the global nickel boom of the 1960s and 1970s, with increased demand for the strategic metal for the space race and arms manufacture during the war in Indo-China. Migration then dropped after the 1975 global financial crash at the end of the long post-war boom.

Today, the French State generates detailed data that helps track this changing demography. The Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies in New Caledonia (ISEE-NC) has a useful website, which collates and analyses data on employment, the economy and society, including population trends. There are regular analysis reports drawing on five-yearly censuses. Data from the 2014 and 2019 censuses are available online (although this year’s scheduled census has been delayed by the current crisis).

Figure 2, using data from five-yearly censuses since 1969, shows net births (solde naturel) and net migration (solde migratoire). It shows that from the mid-1990s, there were increases in both the birth rate and migration for nearly twenty years.

Figure 2: Demographic growth and its components since 1969 (net migration and net birth rate)

Source: Recensement de la population 2019 – Nouvelle-Calédonie (Synthèse N° 45 – ISEE-NC).

Data from the 2014 and 2019 censuses revealed, however, that emigration rates had started to shift. A 2020 ISEE-NC population study documented a stream of departures from New Caledonia between 2014 and 2019 – a trend that has continued since then. As ISEE-NC reports: “Between 2014-19, 27,600 people who lived in New Caledonia in 2014 left the archipelago (i.e. 1 in 10 inhabitants) … The apparent migratory balance is in deficit by 10,300 people between 2014 and 2019 (i.e. 2,000 net departures per year).”

We need to unpack the detail of these figures. Some departing citizens were leaving temporarily (for military service, medical care, or tertiary studies in France). Some were New Caledonians seeking greener pastures. But as ISEE reports, “three quarters of the departures were people not born in New Caledonia”.

The departure of these French expatriates has been influenced by diverse political and economic drivers in the last decade.

Under the restricted New Caledonian citizenship created by the 1998 Noumea Accord, many French nationals were ineligible to vote for the local political institutions, as French researcher Sylvain Brouard has detailed: “The number of voters registered on the general electoral lists in New Caledonia (who are excluded from the right to vote in the election of members of the provincial assemblies and the Congress) has increased in significant proportions: from 8,338 voters in 1999 (7.5% of the general electorate) to 18,208 in 2009, 40,957 in 2019 and 42,596 in 2023. It therefore now reaches one in five voters.”

Beyond anger over taxation without representation, business confidence had been damaged by years of uncertainty around the three referendums on self-determination between 2018-21, overlaid by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-21. Then New Caledonia’s crucial nickel industry foundered, facing industrial disputes, rising energy prices and competition from Chinese investment in Indonesian smelters. The withdrawal of capital from joint venture partners like Glencore was a telling blow for the industry, with much production now shuttered by the current crisis.

Facing all this, many French nationals have voted with their feet. As shown in Figure 3, net migration (solde migratoire) since 2019 has been negative and the number of departures has continued – and even risen – over recent years. Indeed, ISEE-NC reports that New Caledonia’s population peaked in 2019 at 271,285, dropping to 268,510 by 2023. Net migration data shows 19,807 people left between 2015-22 – and a majority of those departing were French nationals rather than New Caledonian citizens.

Figure 3: The population is decreasing; the net birthrate does not compensate for the migration deficit

Source: Civil status and population census (ISEE-NC).

The recent riots – damaging businesses and public and private infrastructure – will likely contribute to a further exodus. Some French business-people and investors see a bleak future for their operations and may throw in the towel, returning to France. As shown by other regional crises, such as the coups in Fiji, people with capital or skilled professionals will be snapped up by other countries. As one example, the state broadcaster NC1ere reported last week that “since the start of the crisis, the New Caledonian Board of Physicians has recorded nearly 80 requests for deregistration. In June alone, 30 general practitioners left the territory”.

So, beyond the political debate about sovereignty and independence in New Caledonia, the coming months will also focus on economic reconstruction and rebuilding human capital. The crisis is New Caledonia has a long way to run.