All non-citizens who seek employment in the private sector in Papua New Guinea (PNG) must possess a valid work permit, issued by the Department of Labour and Industrial Relations (DLIR). DLIR maintains a database of work permits issued per year and of active work permits. This data can be accessed to understand trends and changes in the foreign workforce employed in PNG. Interestingly, the data show that the largest economy in the Pacific islands region only attracts a small number of Pacific island workers to it. Why?

How many foreign workers in PNG are Pacific islanders?

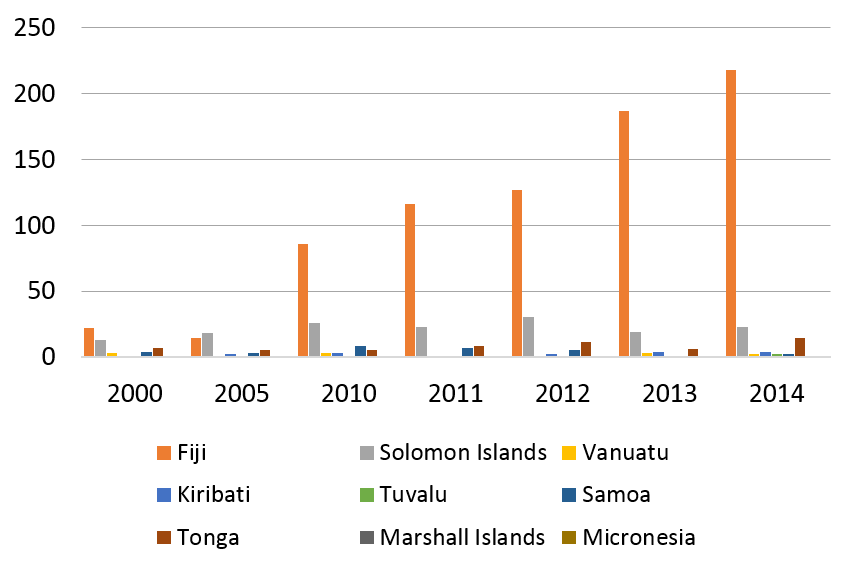

The number of work permits issued to Pacific islanders has increased rapidly in the last ten years, from a low of 43 in 2005 to 266 in 2014 (see Figure 1). Fiji dominated the numbers in all years for which data are available, except for 2005, when the largest number of work permit holders were from Solomon Islands.

Figure 1: Work permits for PNG issued to Pacific islanders, 2000 to 2014

Source: DLIR, annual work permit data

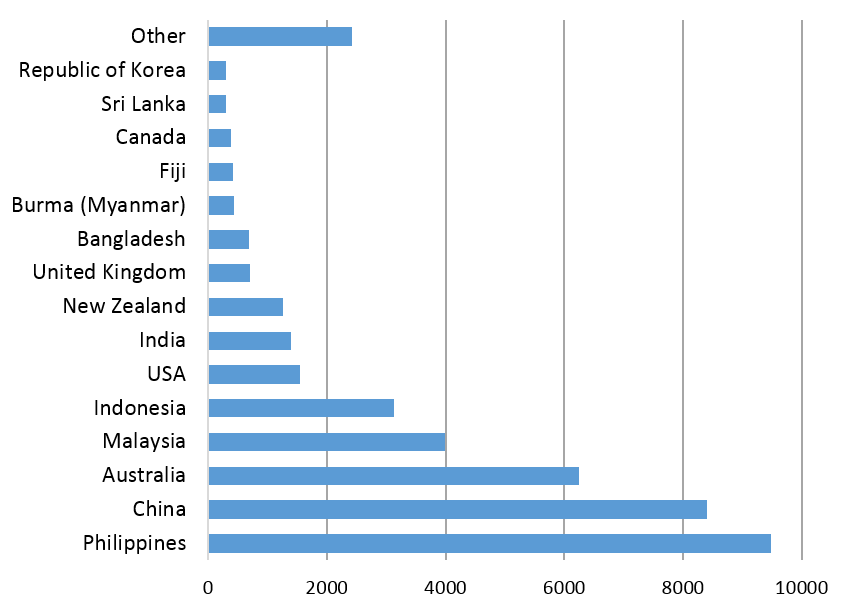

Even so, the overall number of work permits for foreign workers in May 2015 was 41,096. Figure 2 shows the 15 largest source countries of foreign workers in PNG. With 413 work permit holders, Fiji is ranked 12th and is the only Pacific island country in the list.

Most foreign workers in PNG are from various Asian countries, Australia and other industrialised English-speaking countries. While the numbers of workers from Pacific island countries has increased in line with the increase of foreign workers in PNG generally—as a result of the mining boom and the LNG construction phase—geographic proximity and shared membership in Pacific regional or sub-regional organisations have not resulted in any significant movement of workers into the region’s largest economy.

Figure 2: Nationalities of work permit holders, May 2015

Source: DLIR, active work permit data, May 2015

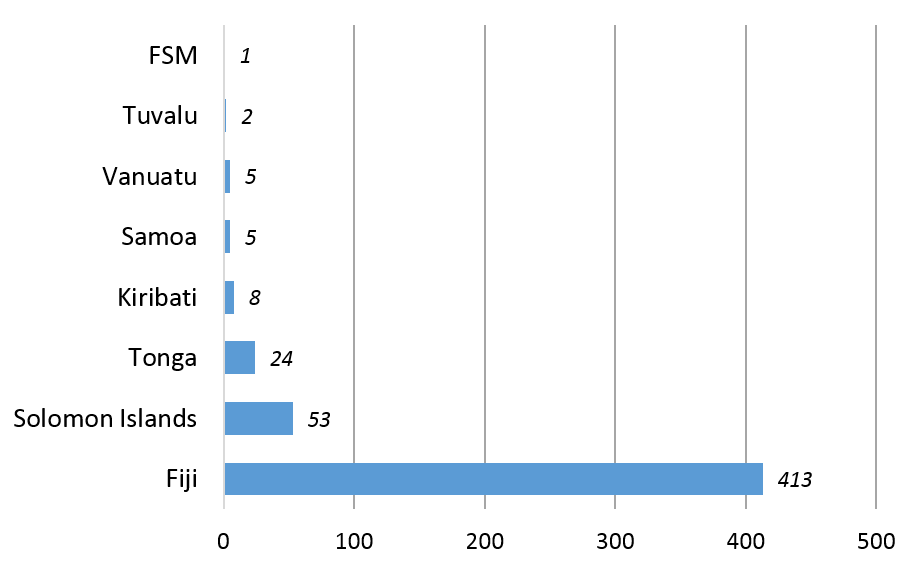

In May 2015, 511 foreign work permit holders were from Pacific island countries, which is equivalent to only 1.2 per cent of the total 41,096 active work permits held by foreign nationals. Except for Fiji, Solomon Islands and Tonga, numbers from the other Pacific source countries were less than ten permits per country (see Figure 3), and there were no workers in PNG from several Pacific island countries such as Cook Islands, Palau, Republic of Marshall Islands and Nauru.

Figure 3: Number of work permits held by Pacific islanders, May 2015

Source: DLIR, active work permit data, May 2015

Looking at some demographic characteristics of workers from Pacific island countries in PNG in May 2015, there were 96 women (18.8 per cent) and 415 men (81.2 per cent) among the 511 Pacific islander work permit holders. The proportion of women among Pacific islanders was higher than for all work permit holders, where women make up only 12.3 per cent. The average age of Pacific islanders was similar to that of work permit holders from other countries. The average age of Pacific islander workers in PNG was 41.0 years, compared to 42.6 years for all work permit holders. There was no difference between the average age of Pacific islander women (41.2 years) and men (41.0 years).

To understand the economic profile of Pacific islanders in PNG, the country’s Work Permit System provides a classification of 19 major industrial divisions. However, the industrial divisions in which work permit holders are employed have not been recorded for about half of all permit holders. For the 511 Pacific islander workers in May 2015, the industrial divisions were known for 278 workers. The largest number of these workers were employed in “Transport, Postal and Warehousing” (54), followed by “Construction and Infrastructure” (30), “Information media and telecommunications” (23), “Accommodation and Food Services” (22) and “Health Care and Social Assistance” (22).

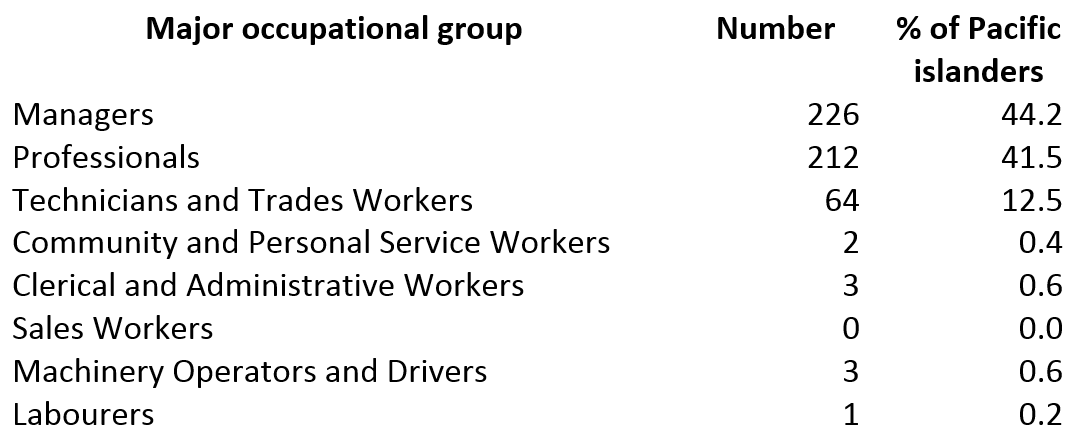

Table 1 shows the number and percentage of Pacific islanders for each major occupational group. More than 85 per cent of Pacific islanders are either managers or professionals.

Table 1: Major occupational groups of Pacific islander workers in PNG, May 2015

Source: DLIR, active work permit data, May 2015

Note: The PNG Classification of Occupations was developed specifically for the work permit system. It is based on the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) and the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANSCO). The PNG Classification of Occupations has eight Major Occupational Groups, which are further divided into Sub-major Groups, Minor Groups and finally, Occupations.

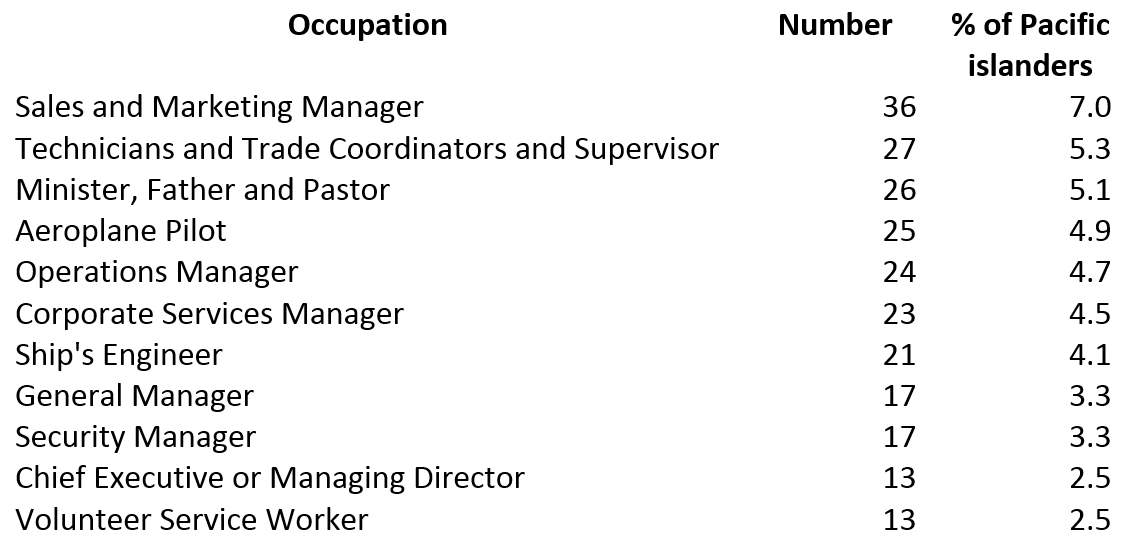

Pacific islanders work in over 100 different occupations. The single most important occupation was “Sales and Marketing Manager”, to which 7 per cent of all Pacific islanders belonged in May 2015 (see Table 2).

Table 2: Ten most important occupations of Pacific islander workers in PNG, May 2015

Source: DLIR, active work permit data, May 2015

Most work permit holders have so-called long-term work permits that are valid from one year up to three years from the date they are granted. Short-term work permits are valid for up to six months. Among the 511 work permits held by Pacific islanders, only two were short-term work permits for six months each, and the rest were long-term work permits, mostly for three years (74 per cent of work permits). Eight work permits were granted for the maximum of five years, which only companies with the status of “good corporate citizens” can obtain for their foreign workers. The average duration of a work permit held by Pacific islanders was 2.7 years.

Bilateral or regional migration schemes haven’t been effective, why?

The movement of Pacific workers into PNG has occurred on an individual basis and not under any bilateral or regional scheme. At present, the Melanesian Spearhead Group’s (MSG) Skills Movement Scheme (SMS) is the only existing sub-regional labour mobility scheme with the objective of facilitating the temporary movement of skilled MSG nationals within the region for the purpose of employment. Although procedures and administrative mechanisms have been established, and the MoU provides for the recognition of certain qualifications awarded in the MSG countries, not a single worker has moved under the SMS between any of the participating countries in the three years of its existence.

The low number of workers from Pacific islands is partly due to several challenges that they face in accessing the PNG labour market. Many big companies are foreign owned and employ workers from the countries where their headquarters are located, or they have established networks with recruitment agents in labour-sending countries, such as the Philippines. In addition, Pacific islanders are not represented in the PNG labour market to the extent that Australian and many Asian workers are, and have as such not had an opportunity to develop networks and gain a reputation as competent workers. Moreover, many Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) systems in the region are not regarded as being of high quality, and consequently there seems to be a perception among employers in PNG that the workplace skills and competencies of Pacific islanders are not of the same high quality as those of workers from some other labour-source countries. The lack of a Pacific Qualifications Framework also means that qualifications are not directly comparable, and not necessarily compatible between Pacific island countries.

In addition to these implementation challenges, stakeholder consultations in PNG have revealed a sense of unease among officials in PNG about labour mobility within the region. Few PNG nationals have had the opportunity to work elsewhere in the Pacific region, including Fiji, where conditions to obtain work permits are stringent, yet a considerable number of Fijian nationals have been able to take advantage of opportunities in PNG. This has led to the perception of unbalanced flows to the disadvantage of workers from PNG. At the same time, Pacific workers face difficulties in accessing the PNG labour market. Hence, only operationalised and functioning regional mobility schemes can be expected to lead to increased numbers of Pacific workers in PNG, as well as workers from PNG in other Pacific island countries.

Carmen Voigt-Graf is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre, and a Senior Research Fellow at the National Research Institute in Papua New Guinea.

Leave a Comment