A study published this month by The Lancet Global Health is the first to demonstrate that community health workers (CHWs) in low- and middle-income countries can be trained to screen effectively for cardiovascular disease risk, a major cause of non-communicable disease (NCD) morbidity and mortality.

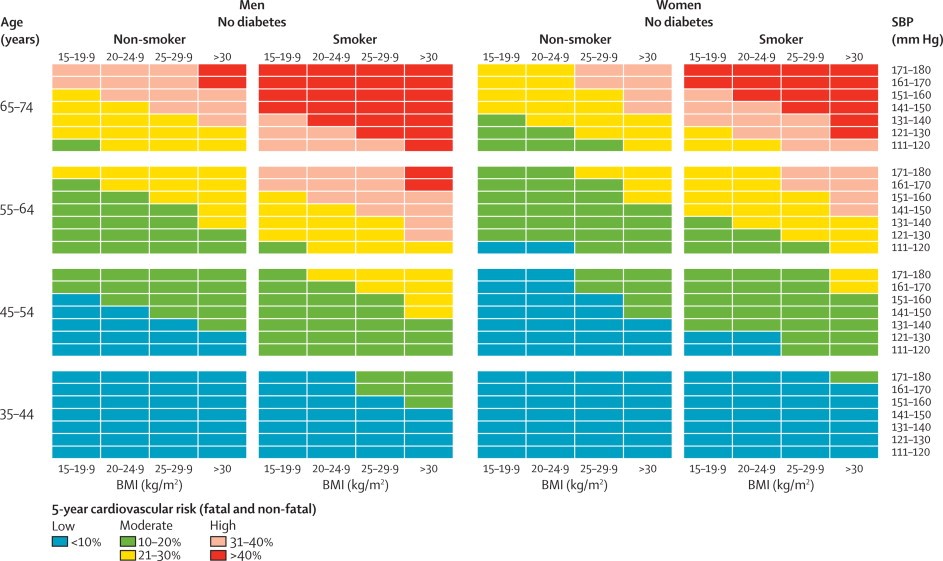

Over 4000 community members between the ages of 35 and 74 in four countries – Bangladesh, Guatemala, Mexico and South Africa – were screened by 42 CHWs using a simple, colour-coded risk identification tool (shown below). The CHWs’ performance was validated by comparing the risk scores they generated to scores generated independently by health professionals (physicians and nurses). On average, 96.8% of the time the CHWs’ assessment matched that of the health professionals.

The study findings suggest that community-based NCD screening is potentially a useful addition to the arsenal of tools and interventions that are needed to address the NCD epidemic engulfing much of the Pacific. Many Pacific island communities also struggle with poor access to professional health care, and could benefit from the services of a CHW who can identify those people who are at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease at an early stage.

Promising though the findings may be, there are some important caveats to note. The Lancet study simply provides proof of concept; the sustainability of CHW programs when taken to scale often proves logistically challenging, as do the ethics of ‘task-shifting’ to CHWs (who are not infrequently volunteers). And while identifying the patient early is an important first step, most NCDs are chronic conditions that typically need long-term management – which requires that patients can access professional health care on a regular basis.

But despite the challenges of implementation, community-based screening for NCDs should not be dismissed out of hand, given the difference that early detection can make. And, importantly, there may also be financial incentives associated with this model – as the authors highlight in their conclusion, there may be significant cost efficiencies to be gained from community-based NCD screening (though a cost-effectiveness study has not yet been done, and the outcomes would likely vary significantly by the specific setting).

Hello Camilla Burkot, Thank you for an insight about the community based NCD screening.

Would like to learn more the equipment / tools used by the health workers to screen the cardiovascular diseases.

Thanks in advance

Hi Saravan, thanks for your comment. The Lancet paper (which seems to be open-access so you should be able to read it here) provides some more details about the training and tools provided to the community health workers as part of this study. Otherwise, if that doesn’t answer your questions, you could try reaching out to the lead author by email (his email address is listed on the paper).

Best,

Camilla

Thanks for the interesting post. I hadn’t seen the Lancet paper. I have two related thoughts about it. First, ‘community health workers’ covers an incredibly broad spectrum of health care providers from people who have had 18-24 months training, a wage and regular supervision to the untrained, unpaid and unsupported. What they share is that they live in the community, reducing the geographic and social distances experienced in accessing care. I am pleased that there is a trend to involving them in NCD health care. My second concern though is that screening is not health care. It is measuring ill health. Knowledge about a person’s health status does not produce better health care without skilled, incentivised and equiped health workers to respond to the information. If the only support a health care system can provide is some broad advice about primary and secondary prevention then there is no need for screening. I was involved in a project in rural Australia that showed that doctors who screened did not respond to the evidence until there was a separate initiative that produced a greater consensus and urgency to take specific action. I have seen that same approach of measuring ill health for the sake of measurement in a number of contexts. Information is great only if there is clarity about what to do with the information. Otherwise information only results in fatalism about high and persistent levels of poor health.

Hi Ann, thanks for your comment. I agree entirely that it is very important not to equate ‘screening’ with ‘care’, and not to assume that putting screening in place is sufficient to improve health outcomes. And I can’t help but think how difficult it would be to try to demonstrate the effect of such a program on NCD outcomes, compared to other community-based programs that focus on, for example, diagnosing and treating malaria, or providing oral rehydration for children. Hence my cautious optimism — depending on all those factors that you raise (training and support for the health workers, linkages to care, access to broader advice about prevention, among others), this may be a helpful intervention but certainly not a panacea!

Camilla