At the Education Effectiveness and Collaboration Forum convened by the Development Policy Centre in March 2012, Peter Baxter, Director-General of AusAID expressed concerns around expertise in Australian universities in the broad domain of education and development.

In response to these concerns, AusAID commissioned a study by the Centre for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Melbourne. The report, A baseline study of the current status of engagement of Australian universities and research institutions in education for development, was discussed at a Higher Education Forum hosted by AusAID on 6 November by a group of about 40 people from universities, AusAID, NGOs, the Australian Council for Educational Research, and government.

In the words of the report “This study provides a baseline analysis of the current status of engagement of Australian universities and research institutions in international development issues that are relevant to Australia’s growing investment in aid for education.” Any fair assessment would confirm the report presents this analysis as well as a good review of the key issues. The report leans a little towards being an inventory of relevant development activity; that the appendices take up nearly two-thirds of the report illustrates this ‘inventory’ approach.

I find that there are three important limitations of this study. The first limitation has to do with the report’s central concept of ‘education for development’. My own engagement with this area has been since 1971 and continued with university work, publications, and numerous long and short-term consultancies since then. It was a field I had always thought of as ‘educational development’. So it was something of a surprise to discover that it has been re-badged as ‘education for development’. This name leads to a sense of confusion. It is unsatisfactory for the study to simply define the field in the negative: “‘Education for development’ is an area of study with no obvious natural disciplinary setting” and then proceed with documentation and analysis of something that lacks a clear focus.

So, what is ‘education for development’? I can see that a good case for using the term can be argued as it does encompass AusAID activities such as the BRIDGE program and scholarships, which are beyond strictly educational development activities. But ‘education for development’ needs clarification and explanation.

Vagueness in locating the field of ‘education for development’ is partly a reflection of the Terms of Reference and partly because AusAID’s key planning documents were evidently not used to construct an understanding of the field that more closely aligned with AusAID’s education aid plans. These key documents are An Effective Aid Program for Australia, 2011 and Promoting Opportunities For All, Education, Thematic Strategy, 2011. The Thematic Strategy provides AusAID’s clear planning structure: access to education, improving learning outcomes, and better governance, management and service delivery. This structure could have been useful in focusing the study. Vagueness also leads to some odd inclusions in the report’s appendices. These inclusions suggest confusion between studies of educational development on the one hand and internationalisation and globalisation on the other. Examples suggesting this confusion are articles about Arts education research in Australia, studies of Singaporean and Hong Kong education, the health of international students in Australia, and French and Australian language teaching in international schools. The term ‘education for development’ has few links on the web and appears not at all in AusAID’s literature as best I can tell, including in the Education Thematic Strategy.

I labour this point because I think the issue of vagueness about the field leads to dubious assertions of the kind “Education for development is weak in robust research inquiry and the associated publishing culture” (page 7). This assertion is questionable if you look through the publishing history of a journal such as the International Journal of Educational Development or the work published by Brian Caldwell and others noted below.

The second limitation is the five-year time frame for the study, 2007 to 2012. This limitation eliminates for consideration the rich and substantial history of the field. The study could not consider and learn from the lessons of early work such as the important support provided to this field by the (then) International Development Program of Australian Universities and Colleges (IDP) described here. Much of this work was done during the 1980s and 90’s in supporting both international development activities by universities and funding of small research projects. This research support led, in my case, to published work on the outcomes of overseas study for Indonesian students and subsequent follow-on design work for AusAID in several countries – a very good example of research informing educational policy and practice.

Another area missing in the study is the academic area generally known as ‘higher education research and development’ of which Melbourne’s Centre for the Study of Higher Education, which produced this study, is one of the world’s finest examples. The intellectual orientations and practices of this field have a very good fit with ‘education for development’ and many practitioners from this academic area made important contributions from around the 1980s onwards in areas that mirror AusAID’s three pillars for its investment in education: access to education, improving learning outcomes, and better governance, management and service delivery. Surely there are some useful lessons for AusAID from this history?

The third limitation is a conceptual weakness. This relates to the discussion in the report around there being two broad groups of disciplinary specialists in universities, those that reside in faculties and schools of education – the ‘pedagogy-rich’ practitioners – and those in area and development studies, who are ‘context-rich’.

There are two matters here that demand further analysis: the assumption that those in education apparently lack context and the further assumption that education is only about ‘pedagogy’. Both assumptions are incorrect. Moreover, in making the assumption that education equates with teaching and learning, whole areas of institutional and organisational change, school improvement, the economics of education, finance, management, governance, and leadership are all at risk of being overlooked. It is exactly the complex interplay of teaching and learning with these areas that occupies so much time and attention in development.

This interplay is very well illustrated in the important book Why not the best schools? by Melbourne academics Brian Caldwell and Jessica Harris and published by ACER in 2008. This is a surprising omission from the baseline study given the important conceptual and practical contributions of these Australian writers to educational development over a long period for Australian schools and for education in developing countries.

Recommendations were not called for in the Terms of Reference. Therefore, it is a pity that only three brief paragraphs were devoted to synthesizing all the work done in the study. Given that we heard at the Forum about the depressing prospect of Australian expertise in the area fading away, then urgent action is required if Australia is to retain capacity and credibility in ‘education for development’. Why not some thinking about ways to support the capture of the knowledge from the consultant’s reports mentioned on page 57 and especially from those nearing retirement before this is lost?

Finally, to apply the concepts of supply and demand to the study, we find almost all the discussion to be on the supply side of the evidence base and skills required for ‘education for development’. But what of the demand for, and use of, the results of any supply side success? We need to hear very much more about this to help AusAID with its stated intentions, set out in the Terms of Reference 2.2: “The paper will be used to inform AusAID’s approach to strengthening the quality, quantity, and use of educational research, study and training in the aid program”.

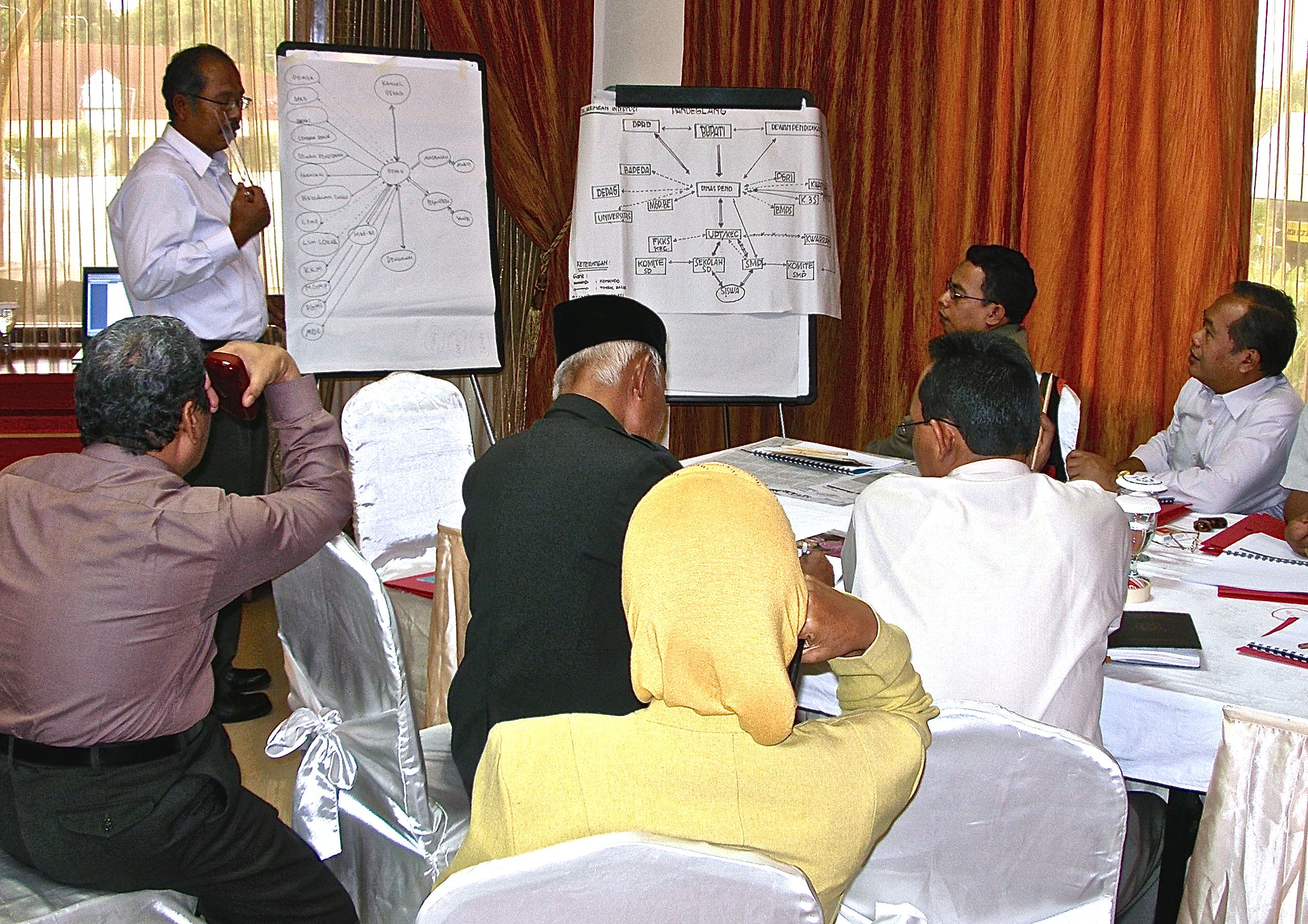

Robert Cannon is an Associate of the Development Policy Centre and is presently working as an evaluation specialist with the USAID funded PRIORITAS Project in Indonesian education.

Teaching and learning improvements cannot take place without appreciating the governance issues. For example USP Suva, Fiji is wasting a lot of money provided by donar agencies including Ausaid. You really feel sad seeing that this money is not reaching to needy people; instead greedy people at top are caring and sharing through corruption.

Bob: I always find kernels of wisdom in your reviews. I am especially struck with your comment: “…in making the assumption that education equates with teaching and learning, whole areas of institutional and organisational change, school improvement, the economics of education, finance, management, governance, and leadership are all at risk of being overlooked. It is exactly the complex interplay of teaching and learning with these areas that occupies so much time and attention in development.”

After working 6+ years on a USAID basic education management and governance project, I’m convinced that teaching and learning improvements cannot take place without appreciating the economics and governance issues. As an over simplified example: projects/program promote pedagogies based on whole language which require children to write as they read which requires lots of paper and pencils.If parents cannot afford the paper or schools decide to build a new gateway to the school instead of buying paper, how does the pedagogy get applied?