A rural health story

It was the impromptu visit to the health centre at Kaiapit in 2007, some two to three hours by road from Lae, the capital of Morobe, that was to leave an enduring memory. It wasn’t the centre itself – it appeared orderly. Nor was it the officer-in-charge – for she impressed as hospitable and alert. What I recall quite vividly was the disturbing image of a young lady lying, curled up, on bed-boards with no mattress. She was motionless and never stirred. Sitting quietly at her side were two older women who recounted in a way that was soulful yet matter-of-fact how they had carried her from their village across a river to this clinic in search of treatment. The OIC explained that her condition was due to complications with her pregnancy.

I’ve often wondered her fate.

In the report Below the Glass Floor we seek to better understand the relationship between rural health funding and the service delivery realities for rural folk in Papua New Guinea. Is what we’re spending delivering on government’s ambition? To understand this relationship as we look through a financial lens, we need to be explicit in what we mean by rural health. We need to identify the service delivery activities in rural health that require money to make them happen. And then we need to compare the amount provincial governments actually spend against what they need to spend to adequately support these service delivery activities.

As we sharpened our focus our analysis looked at six activities in the rural health area (more detail on each is available at the end of this post). The first is funding for rural health facility operations. The second is money for staff to conduct outreach patrols. The third is funding to support the distribution of medical supplies to facilities. The fourth is for money to enable patients to be transferred in emergencies to facilities more capable of treating their condition. The fifth is for the provision of clean water. The sixth, and last, is for staff to conduct supervisory visits to facilities. There is broad acceptance of the validity of this list as these things are both basic and central to a rural health service, which in Papua New Guinea serves 85% of the country’s population.

The study also considers the wider financial context. This includes the adequacy and efficiency of the funding streams from the national to the provincial levels. And the appropriateness of the way money is transferred throughout the system; from the national to the provincial and from the provincial to the district and facility levels. We also explore whether the funding architecture is aligned to properly support the provision of rural services, and if not, what a better aligned architecture might look like.

These are not simple questions to analyse or answer and the more one enquires, the more complex the picture can appear. However, these are surely questions that deserve attention despite the inherent challenges. Below the Glass Floor is the first part of a wider analytical process that encompasses the analysis of National Health Information System (NHIS) facility performance data by the World Bank team and a synthesis of the phase one findings of the commendable research work that interviewed 142 health facilities, recently completed by the joint National Research Institute/Australian National University Promoting Effective Public Expenditure Project (PEPE) team. It is hoped that the pictures that emerge from this collective work can assist government in its endeavours to further improve the rural health service delivery mechanism.

So what are the major findings?

One of the principal findings relates to the national level. The national government has committed increasing amounts of health function grant funding since 2009. However, the study found that the release of this funding from the national level to the provincial level varied each year, and varies markedly across provinces (see the chart to the left that depicts the release of funds by Treasury by the end of February). There was no apparent consistency in the way the health function grants were released, which is in itself a major problem for those charged with planning and implementation. And often, too much money would come too late in the year to support service delivery priorities in a sensible and considered manner.

One of the principal findings relates to the national level. The national government has committed increasing amounts of health function grant funding since 2009. However, the study found that the release of this funding from the national level to the provincial level varied each year, and varies markedly across provinces (see the chart to the left that depicts the release of funds by Treasury by the end of February). There was no apparent consistency in the way the health function grants were released, which is in itself a major problem for those charged with planning and implementation. And often, too much money would come too late in the year to support service delivery priorities in a sensible and considered manner.

A second key finding was the need for clarity over functional responsibility. The government has a mechanism in place for clarifying functional responsibility, the Determination Assigning Service Delivery Functions and Responsibilities to Provincial and Local-level Governments. However, the study found uncertainty in several key areas which [then] correlates to low or no spending in those areas by provinces. These areas are: the distribution of medical supplies, emergency patient transfer and the provision of clean water supply.

The analysis on spending patterns on priority activities reveals a mixed picture. We do see signs of improved spending, sometimes markedly so, on facility operations and patrols. In contrast, the spending on the distribution of medical supplies, patient transfer, water supply and supervision was typically disappointing. One of the difficulties we experienced was the lack of a standardised chart of accounts across all provinces: meaning each province uses a different approach in classifying their budget and expenditure. This makes analysis and interpretation extremely difficult.

The analysis on spending patterns on priority activities reveals a mixed picture. We do see signs of improved spending, sometimes markedly so, on facility operations and patrols. In contrast, the spending on the distribution of medical supplies, patient transfer, water supply and supervision was typically disappointing. One of the difficulties we experienced was the lack of a standardised chart of accounts across all provinces: meaning each province uses a different approach in classifying their budget and expenditure. This makes analysis and interpretation extremely difficult.

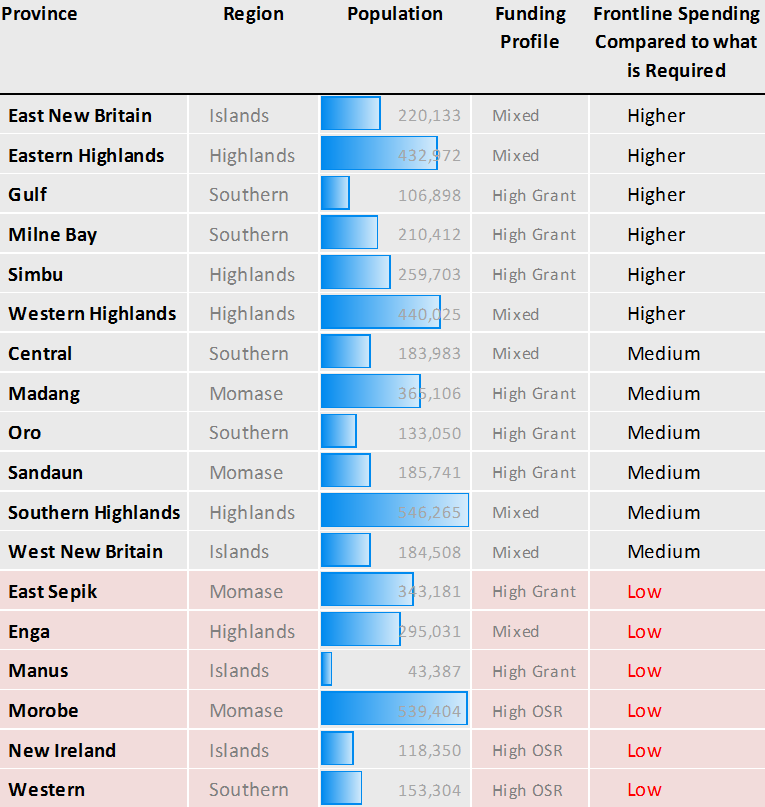

The analysis of the eighteen provinces reveals eighteen stories. Whilst we can force some general findings, the informed reality is more nuanced (perhaps not unpredictably), with each province having its own story across the five years of data and the six key activities. Nevertheless, the table to the right collates the findings to form a profile of spending by each province on frontline activities. It is disturbing that provinces with higher levels of own-sourced revenue (such as GST and resource revenue) typically spend less on rural health. The consequence of this should not be lost: rural health in Enga, Morobe, New Ireland and Western will not improve until these provinces allocate more revenue to key service delivery activities in rural health.

In conclusion

The World Bank recently convened a workshop in Port Moresby that involved participants representing both provincial and national level views. There is a consensus that many frontline rural service delivery activities in health emanate from rural health facilities – it follows that funding for facility operations, patrols, (very) basic maintenance and some emergency patient transfer needs to be ring-fenced and accessible at the facility level. Making progress on how to better fund facilities is a priority issue. Some issues require national leadership and sympathetic support from central agencies to progress. The Department of Provincial and Local Level Government (DPLGA) together with the Department of Health can help resolve the unclear aspects of function assignment (i.e. who is supposed to do what). Another recurring issue is the flow of funds from the national level – the Department of Treasury hold the key to this.

More broadly, the architecture of the sub-national level continues to change and adapt with the advent of Provincial Health Authorities (PHA’s) in some provinces (PHA’s are new entities formed to manage all aspects of provincial health – including the provincial hospital and the network of rural health facilities) and discussions around the new concept of the District Development Authority (see the recent DevPolicy blog post by Colin Wiltshire). The realities of implementing new mechanisms that will in turn create new actors across the country presents as a large challenge. These new institutions will need to be carefully woven into the existing fabric of the government service delivery chain if the desired improvements in service delivery are to be achieved. If this fusion does not take place the unintended result may simply be a more convoluted system with even more actors.

The antidote for all of these challenges is to keep our eye on the ultimate objective, to maintain a clear line-of-sight of what we mean by frontline service delivery, and for the key participants at the sub-national and nationals levels (Provincial Administrations, PHAs, churches, Treasury, Finance, Provincial and Local Government Affairs, et al.) to continue with their commitment to jointly resolving the issues that inhibit the aspirations of government.

Below the Glass Floor was published by the World Bank in partnership with the Papua New Guinea National Economic and Fiscal Commission and the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Alan Cairns is a consultant on the World Bank’s health analytic team and an adviser on the DFAT Provincial and Local-level Governments Program, which provides assistance to the National Economic and Fiscal Commission.

Summary of findings on spending to support front line activities

Rural Health Facility Operations (MPA 1)

- We certainly see increased spending in this area in 2009 and 2010 – eleven provinces spent between 50-100% of what is estimated necessary. The question remains how much of this was eventually spent on facilities? Budget coding can be improved and sharpened in this area.

- In many instances, facility funds appear to be retained and managed from the provincial level. It invites the question as to whether this is an effective arrangement for facilities. Can facility staff access these funds as readily as they need to?

- Facility maintenance is a key activity. There needs to be greater direction and clarity on where the responsibility for this activity and the funding is best managed. Is that at the provincial, district or facility level?

Outreach Patrols (MPA 2)

- In 2009 and 2010 we certainly see increased spending that may be in the outreach patrols space. However, due to generalised coding, it is difficult to know with certainty how much of this spending was actually on outreach patrols as opposed to other activities. Budget coding needs to improve.

- Facility-based staff need easy access to funding for patrols. What is the best arrangement(s) to ensure this happens in practice?

Distribution of Drugs and Medical Supplies (MPA 3)

- Two-thirds of provinces spent little or nothing on this activity in 2010.

- In 2011-12 the National Department of Health assisted by AusAID commenced a program of procuring and distributing 40%, and now 100%, of kits to rural facilities. This essentially recentralises a large part of the rural drugs and medical supply function.

- The distribution aspect of this function is noted as a provincial responsibility in the function assignment determination – with this recent change it needs to be made clear where the responsibility for the function now rests. Is it now a national function? Or is it a dual function, and if so, is there sufficient clarity on roles and responsibilities.

Emergency Patient Transfer (about 23% of the NEFC cost estimate for rural health)

- Despite patient transfer being identified as a major cost in the NEFC cost study there appears to be little funding specifically allocated and spent by provinces on transfers from facilities to hospitals.

- As a matter of policy, should an amount be allocated in provincial budgets for patient transfer? If it is assumed to be the responsibility of the patient’s family, will it affect the access to hospital services for the poor?

- Where should the funding for this activity be managed from – should it be at the provincial, district or facility level? Or should it be distributed to more than one level?

Clean Water Supply (about 19% of the NEFC cost estimate for rural health)

- There is little visible spending on provincial and district supervision activities. How is this critical activity funded? And is the current funding approach effective?

- There is evidence of some spending on this activity across most provinces.

- Is this function a responsibility of provincial governments? And is it an activity for the rural health team to coordinate, administer and implement? If so, it should be noted in the function assignment determination (FAD) administered by DPLGA and funding to support the activity should be allocated.

Supervisory activities

- There is little visible spending on provincial and district supervision activities. How is this critical activity funded? And is the current funding approach effective?

It is wonderful to see this sort of detailed funding analysis published AND promoted. Hopefully this will be a very useful tool for both government staff and community activists working to improve services in PNG.