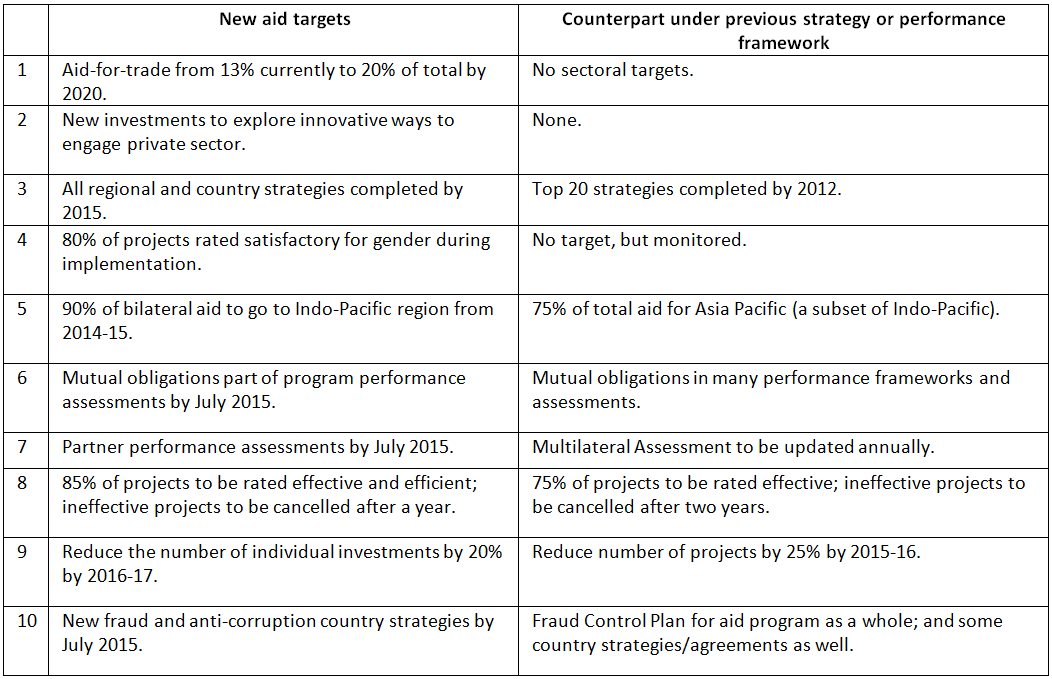

Julie Bishop calls it the new aid paradigm: the Coalition’s new aid program strategy and performance framework. The first thing to say about it is that it is not that new. That is not a criticism. It would not make sense for the aid program to head in a completely new direction every time a new government came to office. And improving aid effectiveness is a bipartisan endeavour that has been underway now for many years. Taking this agenda forward is best done by building on the efforts and achievements of the past. To see the similarity between the old and new approaches, take the ten targets which constitute the government’s new performance framework. As the table below shows, eight of them have at least somewhat (and sometimes very) similar counterparts in the previous government’s performance framework and aid strategy more generally.

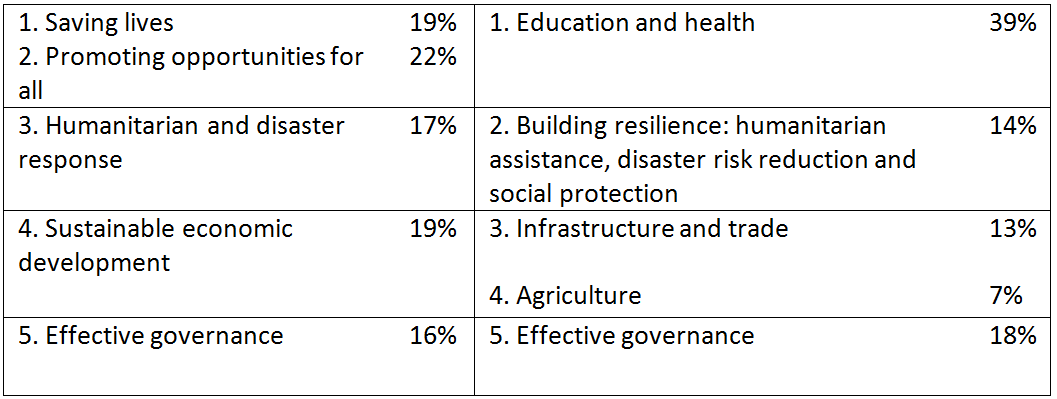

Or look at this comparison of the sectoral expenditure categories of the previous government, and their share of the aid budget in 2013-14, with the sectoral categories adopted by the new government, and their share of the budget in 2014-15 (information for which is now available from the government’s belatedly-issued aid budget or ‘Blue Book’, also released yesterday). There is little difference in the packaging, and, so far, in their shares.

Or look at this comparison of the sectoral expenditure categories of the previous government, and their share of the aid budget in 2013-14, with the sectoral categories adopted by the new government, and their share of the budget in 2014-15 (information for which is now available from the government’s belatedly-issued aid budget or ‘Blue Book’, also released yesterday). There is little difference in the packaging, and, so far, in their shares.

It’s not all continuity though. There are certainly a significant number of changes, including of course the plan to lift aid-for-trade spending. More analysis will be needed, but we focus here on what we consider to be the big improvements and the main negatives.

It’s not all continuity though. There are certainly a significant number of changes, including of course the plan to lift aid-for-trade spending. More analysis will be needed, but we focus here on what we consider to be the big improvements and the main negatives.

First the big improvements.

- The requirement that now projects will have to consider ways to engage the private sector won’t influence traditional technical assistance projects, but could make a big difference in the social sectors, where the aid program will need to consider whether it could do more to partner with, for example in PNG, church-run health services or private sector health providers, actual or potential.

- The emphasis on innovation, the $140 million innovation fund and a willingness to take risks are all positives. Our Australian aid stakeholder survey last year revealed that most thought that AusAID should be prepared to take more risk.

- The elevation of gender, for the first time, to become one of the six priority areas for the aid program, alongside the five sectoral categories given above, is a positive. Gender is not a sector: projects promoting attendance of girls at school will instead be classified as an education investment. But it is nevertheless good to put gender up in lights with the other five sectors: its previous treatment as a crosscutting issue, while logical, perhaps meant it didn’t get the attention it deserved.

- Some of the targets introduced are ambitious and will not be easy to meet. The figure below (from a recent Office of Development Effectiveness (ODE) report) shows what the baselines are. Satisfactory scores for effectiveness and efficiency are normally below the new target of 85%, and satisfactory scores on gender are normally below its new 80% target. Of course, these are self-ratings, and standards can be lowered to meet the new targets. But the ODE will be doing spot-checks to keep the self-rating bias under control, and it’s got to be an improvement to have more ambitious targets than the earlier, single 75% effectiveness target, which was always guaranteed to be met, and therefore irrelevant.

And now the main negatives, all of them omissions.

And now the main negatives, all of them omissions.

- Aid transparency has declined so far under the new government. The new strategy recommits to transparency, which is good, but transparency is dropped from the performance framework. Since reporting will be based on the ten targets, and transparency is not one of them, that may well mean less emphasis for transparency. The last government, despite committing itself to report annually on its progress with transparency, struggled to keep project information up-to-date on the web. Not making transparency a performance target is a mistake.

- Another area the performance framework is silent about is actual results. The old performance framework was full of quantitative targets such as “40,000 women survivors of violence will receive services, including counselling.” There were in fact 17 such output or outcome targets. The new performance framework has none. The previous government went too far, we argued, with its emphasis on output targets. Nevertheless, they are, at a minimum, good tools of communication. Compare the old target above with the new government’s gender target: “80 per cent of investments, regardless of their objectives, will effectively address gender issues in their implementation.” Is that really going to impress or excite anyone except an aid wonk? The Coalition is to be congratulated for focusing its performance framework on things that are under Australian control and are reasonably easy to measure (such as ratios and ratings) but some supplementation by more easily understandable, communicable and tangible results would have been helpful.

- The government has only done half the job it set itself. It answers the first question in its consultation paper (“How should performance of the aid program be defined and assessed?”) but not the second (“How could performance be linked to the aid budget?”). There is to be a performance incentive fund (another instance of continuity with the past), but no hint is provided of how the basic challenge of linking performance to aid allocations at the country level will be met beyond the anodyne: “Progress by both Australia and its partners in meeting mutual obligations will be assessed and reflected in future budget allocations.” Experience shows that without an explicit formula linking performance to allocations either across countries or across time, such an intention is simply not credible. The difficulty of converting good intentions into reality was in fact illustrated yesterday at the launch of the aid policy itself. Yesterday was the day when the PNG Prime Minister sacked his anti-corruption chief after the latter accused the former of corruption. Given the prevalence of corruption in PNG and the heavy emphasis placed on corruption by the aid program, if there was ever a case of a country not meeting its “mutual obligations” this was it. And yet our Foreign Minister happily announced, at the launch, that we are in fact increasing aid to PNG.

- Not enough attention is given to aid management in the performance framework, and not enough to what aid stakeholders see as the problems with the aid program. When we asked over 300 aid stakeholders in our survey last year what they saw as the problems in the aid program, they said rapid staff turnover was the most serious, and slow decision making the second. The old performance framework included a commitment to reduce staff turnover. That has been dropped. Timely decision-making features in neither framework. These might seem like prosaic things, but they are critical for effective aid. And if we can’t manage regular aid well, you can forget about innovative aid. Especially with the DFAT merger, aid management threatens to be the Achilles Heel of Australia’s aid program. It is unfortunate it has been marginalized in the new approach.

Criticisms invariably take longer to express than praise. The new strategy and performance framework clearly has both strengths and weaknesses. Its continuity is itself a major strength, and it is good that we now have a new underpinning for the aid program, and within only a year of the Coalition taking office.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre. Joel Negin is Senior Lecturer in International Public Health at the University of Sydney.

WhyDev put up a great comment on Twitter on this post, saying that there was another problematic omission in the new strategy: climate change. Since I couldn’t think of a 140-character response, I’m responding here.

The words ‘climate change’ do actually feature once, but only once in the strategy. I agree that the topic is, if not omitted, then very much underdone. My only defence of our omission of this almost-complete omission is that the latter unfortunately reflects a problem with the Coalition’s lack of commitment to serious action on climate change (both at home and abroad) more broadly rather than with their aid policy per se.

Not sure if people saw this but Indonesia has pledged $20m to help Pacific Islands fight climate change. So Indonesia (a large aid recipient) is stepping into the gap vacated by Australia. Interesting times!

Great blog! Is the new aid policy available online? If so, where can it be accessed? Thanks!

Hi Tana, yes it is available here on the DFAT website: http://aid.dfat.gov.au/aidpolicy/Pages/home.aspx

I agree with you Stephen that continued incremental reform of the aid program is a good thing and I hope that many of the ideas promoted by the Government are a success. There is room for improvement and we should be open to innovation. However I notice that the minister relies heavily on problems with aid to PNG to explain the need for reform. It is true that PNG may not reach any of the MDGs by 2015 but an analysis of Australia’s main developing country partners shows that PNG is not at all typical of their performance. Of the 14 largest aid recipients only PNG and Afghanistan are doing poorly on the MDGs. The other twelve all score 55% or higher when assessed using the Center for Global Development/DATA MDG Index.

Hi Garth,

I 100% agree. Listening to the Minister’s words, she mentioned that aid had failed to meet expectations and that we can’t continue to spend billions and get no results. But especially in her answers to the questions from the journos, it did start to seem clear that the rationale for the “new paradigm” is largely driven by perceptions of failure in PNG. It’s a bit odd – where countries have succeeded, it represents the success of trade and economic growth (aid is irrelevant); where countries have not succeeded, it represents the failure of aid (and not the failure of trade or economic growth). So aid can’t really win. So in PNG, it is not that economic growth and trade has failed to take hold or lead to progress but rather that aid has failed.

The idea that aid is a panacea is a strawman – I don’t think anyone in the aid community actually ever argued that aid alone would solve all development challenges.

Joel

Great blog, as usual. I’d like to add another aspect, not an omission but just an inconsistency that is at odds with the focus on ‘innovation’, notably that ‘ineffective’ projects get axed after one year. This also reeks of ignorance of real world contexts.

On what basis would projects get axed? Ineffective defined how? Inability to get project staff at all levels in place quickly enough? This often takes lots of time. Inability to align the implementing partners when there are multiple organisations involved? This also often takes quite some time. Inability to show progress with outputs? How often are activities up and running quickly? Inability to show results? Of course impossible.

A one year timeframe effectively annuls any opportunity for project-level innovation, adaptive management and learning. Clearly only willing to take 140 million dollars worth of risk.

Hi Irene,

That is an excellent point. Good development practice implies a long-term partnership over 10 years (or at least 5) where trust is built and innovation and mutual risk-taking is allowed. One year windows to judge success or failure does not mesh well with the realities of projects nor the reality of innovation. Not sure how that will be balanced. I do wonder how many projects will actually be axed after one year.

Joel