Education is a central concern in much of the writing on development policy and planning. AusAID, for example, has clearly articulated the importance of education in development in these words [pdf]:

Promoting opportunities for all is one of the five strategic goals of Australia’s aid program… Education is an enabler of development and crucial to helping people overcome poverty. Education makes a significant difference to improving equity, health, empowering women, governance and sustainable development.

Statements about education in development often refer to matters such as poverty, teacher training, management, equity and buildings. Astonishingly, we see little about learning, an issue of central importance. Just as effective learning is essential in schools, effective learning is the key to the success of many development strategies. Development that has a lasting impact depends on beneficiaries understanding their needs and learning of ways to address these needs independently and on a continuing basis.

The processes of learning are not widely understood in the development community, particularly the evidence about how young adults approach learning and how their context shapes the way that they learn.

The following discussion is based on research in student learning in higher education and studies I have completed in Indonesia. The discussion then links this work to propositions about learning in the context of development programs and projects.

Applying learning research to development [1]

In the 1970’s, two Swedish scholars, Ference Marton and Roger Saljo, shifted the attention in learning research towards what students actually do and think in real situations (their original work is available here, an introduction to the research can be found here). They found that student’s perceptions of their context influenced their approach to learning and that their learning could be described in terms of a deceptively simple dichotomy between a deep approach to learning, where the student seeks personal understanding, and a surface approach, where the student focuses on the reproduction of material presented during the course of their studies.

The deep-surface dichotomy has had a profound impact on the way teachers now think about the impact of their teaching on student learning. The research conveys an important message: it invites us to consider education from the student’s perspective.

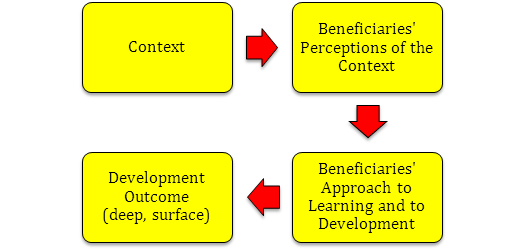

Can we adapt these ideas for a better understanding of development from the beneficiaries (as learners) perspective? I believe we can. So, how can these ideas be applied in development? In development activities it is possible to observe beneficiaries adopting distinctive approaches to development. These approaches are strongly influenced by their context as shown in the diagram.

A learning approach to development

The context includes local culture and values, education qualities, community involvement, leadership and policies, in addition to the characteristics of the developer’s implementation strategies.

The effect of this context is to influence beneficiaries’ perceptions of the demands of that context and their resulting approach to development. In the simplest analysis, beneficiaries may be observed to use one of two broad approaches to development called a surface approach or a deep approach – the same terms used in learning research.

Beneficiaries using a surface approach fulfil the requirements of a development activity by using learning processes such as memorising basic information without really understanding it. In some of my work, I have observed beneficiaries to:

- Participate passively in the development activity

- Confuse principles, evidence and strategies

- Reproduce ideas without understanding them. In the workplace, they may reproduce, or even copy a strategy from somewhere, without really understanding the strategy.

The approach of these beneficiaries using a surface approach is to minimally meet formal obligations and to focus on the task. There is poor understanding of the principles and evidence supporting the task and of ways to adapt to new challenges. The links between the principles underpinning the task and the intended development outcomes are poorly understood, if at all.

In the same way that a student’s approach to learning will be influenced by their teacher’s approach to teaching – and the examinations – the reasons for beneficiaries adopting a surface approach can be found in the developer’s approach to development and in the reward system. Training programs led by poorly prepared trainers, who themselves may not understand what they are teaching and why, may be such an approach. This lack of understanding may occur when cascade-training approaches are used to reach large numbers of beneficiaries. Distortions are created as the training proceeds down the cascade meaning that lower levels miss essential concepts and that the final implementation may be wrong or bear little resemblance to what was intended.

Receiving this kind of training, the development outcome may be superficial recall of basic strategies and an inability to apply the strategies at work. These stakeholders are often externally motivated by regulations or the expectations of their supervisors. They see change as being important only because it is imposed from the top and because they may fear the consequences of not doing what authority expects of them.

Stakeholders adopting a deep approach to development are motivated by strong values, a genuine interest in the task, a need to understand the principles informing the change as well as the technical material, and to be able to apply new knowledge for the benefit of their organisation. Here, I have observed that their intention is to develop a deep understanding of the new strategy, the evidence supporting it and the understanding necessary to develop adaptations. I suggest that these stakeholders are intrinsically motivated. They see change as important because of their values and because of their understanding of the needs of those for whom they have responsibility.

The surface–deep approaches, and external–internal motivations in development that are proposed in this simple analysis reflect the same principles that now inform changes in learning and teaching in education. This change is from teacher-dominated externally motivated learning driven by exams and fear of failure, towards student-centred, active learning motivated by curiosity, interest, enthusiasm, and understanding.

Towards deep, sustainable educational development

As long as educational developers maintain a top-down approach led by donors and central governments, they will be working against change that should be driven by local needs and initiative, active and continuing learning, and effectiveness. Large-scale projects and ‘sector-wide approaches’ (SWAPs) in development risk embedding surface approaches by design (a recent Devpolicy blog provides a helpful review of the concept). Both risk spreading limited development resources widely and thinly at the expense of attention to a more focused ‘sector-deepening’ approach.

How might deepening be achieved in development? My work in Indonesian education suggests that the following strategies are likely to support deeper approaches: gathering valid data in identifying local conditions and needs and then targeting these, aligning development strategies with government policy, building on earlier development initiatives, investing time – several cycles of training, mentoring, providing feedback and support over years (in contrast to ‘one-shot training’), using local expertise, training multiple stakeholders from government and schools together, using a whole-of-school development approach in contrast to selecting only one or two persons for training, and building local and sustainable communities of professional practice. [2]

Deepening strategies are not common in educational development projects. It is my experience that after project completion, very modest, continuing, technical support can lead to sustaining, deepening and disseminating changes from development activities. Unfortunately, governments and donors seem to prefer to move on, to ignore many of the lessons learned and to create new approaches with new problems in new locations with new support staff.[3]

I believe deep learning is an appropriate concept to apply in development. It is a necessary concept for sustainable development. Just as we should not expect students to learn complex behaviours and develop deep understanding from a few formal lectures, neither should we expect complex government organisations, universities, schools and teachers to learn from comparable surface interventions. But this is what has happened in the name of ‘development’. Perhaps this is why achieving deep, sustainable change impacts remains a continuing challenge for us in development.

Robert Cannon is an Associate of the Development Policy Centre and is presently working as an evaluation specialist with the USAID funded Palestine Faculty Development Program and the new USAID PRIORITAS Project in Indonesian education.

[1] Some empirical support for the propositions presented here can be found in Kirby, J.R., Knapper, C.K., Evans, C.J., Carty, A.E. and Gadula, C. (2003). Approaches to learning at work and workplace climate. International Journal of Training and Development, 7,1: 1–52.

[2] See: Cannon, R. A., & Hore, T. (1997). The long-term effects of ‘one-shot’ professional development courses: An Indonesian case study. International Journal for Academic Development, 2, 35-42; Cannon, R.A. (2001). The impact of training and education in Indonesian aid schemes. International Journal for Academic Development, 6, 2, 2001: 109 – 119; Cannon, R.A. and Arlianti, R. (2008). Review of Education Development Models, The World Bank, Jakarta. 146p. (Available from the author.)

[3] Aid and the Maintenance of Infrastructure in the Pacific, written by Matthew Dornan on March 29, 2012 for The Development Policy Blog addresses some of the unfortunate outcomes from this approach. ( https://devpolicy.org/aid-and-the-maintenance-of-infrastructure-in-the-pacific/ )

it is a nice lesson

Hi Bob,

Thank you for a most useful application of notions of ‘surface and deep’ to ‘development.’ I am currently coming to the end of an Australian Volunteers International assignment in a university in north west China, and soon to start another similar assignment in Vietnam. The issues presented are dear to my heart.

Your blog (that I was a little surprised I could access, given certain restrictions in China) provided something of a ‘refresher’ in Western ways of thinking and expressing. I saw your reference to ‘context’ as critical, to the extent that context has the potential to significantly impede open intellectual debate.

Within a ‘Western development provider’ constituency, I would hope that what you present receives a considered hearing as I strongly support the positions presented in the blog. Part of the challenge is the difficulty, both technically and politically, in evaluating and reporting on the effectiveness of development. Further, currently the ‘surface approach to development’ is so often accepted with such appreciation that the need for, and added benefit of, a ‘deep approach to development’ would be seen as unnecessary by many ‘donors’ and ‘recipients.’

I hope that during my year in China I have been ‘walking the talk’ at the coalface of Chinese university classrooms. The students are receptive!

Hi Owen,

Great to read your reply. I particularly appreciate the observation about the forces of demand operating to encourage a surface approach. This acts as a very useful counterbalance to the forces demanding depth that I have been seeing recently and my general view (confirmed by you also) that donors seem content to supply surface development, although this would likely be hotly denied. Best wishes, Bob.

Robert, thanks for the insight. I have also been intrigued by where notions of learning might sit in a broader development context. No doubt we need to think carefully abut the quality of learning that takes place within education programs, but we rarely look further to how it plays a role in the full spectrum of aid interventions.

My doctoral research took up this challenge by applying a phenomenographic methodology (built around Marton’s work) to an agricultural program in Mozambique. What was particularly interesting in using this approach was the surprising diversity of ways that stakeholders engaged with the project. Putting these observations into a learning hierarchy was helpful in highlighting how different the impact of a development program can be for members within the same community. Understanding these differences can be particularly powerful, but only if we allow for diversity in how programs are delivered and designed. This means using research in the area to encourage donors to allow innovative and alternative development models to be trialled as an additional and necessary part of their standard programmatic work. We set aside a designated proportion of funds for monitoring and evaluation (M&E), so why not look at having a percentage set aside for learning and innovation that is properly thought through and recorded.

Christopher, your final suggestion is excellent and one that would really add weight to the assertions in M&E that we are truly interested in learning (when I suspect that 90% of the real agenda is accountability). It would be great if you could find time to write a blog here about your work on learning as, being research-based, it would advance the discussion considerably. In any case, can you provide a reference or a link to your work?

Robert, publication of my thesis is forthcoming (next month or two) and I would be happy to put something together for the blog on learning as that is the central tenet of the thesis. In essence, I argue that our heavy focus on the instrumental nature of indicators as the measures for success means we miss some of the good stuff (and the bad!) because we don’t seek to dig further into what is really going on and reflect on what this might mean for how we deliver our programs. My big push is to look at a broader range of evaluative methodologies to learn from development work that builds on the approaches already being utilised.

Chris.

Great! Please do write a blog.

As I am presently writing indicators for a new, major project in Indonesia, I wish I had your knowledge and insights right now. So if you can do the blog yesterday, it would be very helpful!!

Robert Cannon’s blog ‘A deep or surface approach to development – what can learning research teach us?’ points to the potential shallowness of cascade training approaches, especially when carried out as ‘one-shot’ training exercises, and emphasises the need to take a deep approach to learning. He raises important issues that affect capacity development, change management and the achievement and sustainability of good development practices.

The essential pre-condition for capacity development and for effective change programs is that a supportive environment exists or can be developed. It is not enough that the proposed program be supported by senior officials, it must also be supported by those closer to the action. Clearly, people will only support change programs if they at least conditionally accept the need for change. They also need to see that there is a realistic way forward to achieve the change, that they have or will acquire the necessary knowledge and skills, and they need to be supported throughout the change process. A one-shot surface approach by program implementers is unlikely to meet these conditions.

Training alone is not capacity development. True capacity development requires much more than the training of specified target groups. Supporting changes to systems, process and procedures will almost certainly be needed, as well as parallel development activities for other stakeholders than those initially identified. The development process will be iterative and based on on-the-job learning and continuous quality improvement is therefore essential. All of these issues require deep understanding and engagement by the people involved.

Post-program sustainability depends on local ownership and requires deep commitment by local stakeholders. Also, simply mainstreaming new practices is not a sufficient test of sustainability. True sustainability requires that these practices can be updated and improved even when no external support is available. Again, people need to have a deep understanding be able to do this, which is unlikely to be achieved through conventional cascade-training.

These are serious problem for program planners, who will likely face time and budget constraints. The issue with cascade training is that the training of a particular target group (e.g. 1,000 science teachers) is seen as being the priority. Part of the answer for planners is to conceptualise the key task as one of trainer/mentor development, with the initial teacher-training activity being part of that development program rather than being the end in itself.

I was part of a team working with District Education Services to support the implementation in schools of the Indonesian Government’s policies on active learning, school-based management and community participation; as well as to support the capacity development of the Services. Rather than pursuing targets for project-support training, we emphasised the development of a group of local trainers in each District.

We modified the cascade approach to include a mentoring stage. Our national consultants ran the initial trainer training, then mentored the trainers as they planned and delivered their first few cycles of cascaded training, supporting ongoing improvement in the quality of the courses. With our ultimate goal being that all potential stakeholders were trained (and not just the relatively few funded by the project), these initial courses were primarily seen as a way to train the trainers – and we did meet our training indicators.

This linked training/mentoring approach was repeated by the local trainers, who followed up their formal training with in-school mentoring. This proved to be a successful way to minimise the potential losses and distortions likely in cascade training.

Over time and with mentoring support our trainers developed competence and confidence as professional trainers, able to continue the project-initiated training and mentoring programs, adapt and improve them over time, and design and deliver local, low-cost programs for other stakeholder groups. Being local, they could be effective in influencing teachers, parents and the community to support the changes, providing ongoing local support and serving as ‘change champions’.

In effect, this approach applied the strategies supporting deep and sustainable development summarised in the Cannon blog. It aligned with government policy and earlier initiatives; provided several cycles of training, mentoring and feedback; allowed for whole-school and whole-system development and built communities of professional practice in Districts and across the Province.

From a planning and implementation point of view, this is a relatively low-cost strategy. The major expenditure is at the beginning of the process, with the selection, training and mentoring of trainers through the first cycles of training. The actual cost of training and mentoring teachers, school committee members and principals by local people, carried out locally, is low and allows for near-100% coverage over time. The time demands on project consultants are heavy at the beginning and decline over time. This decline in cost and time demands on a project provides for an easily-understood exit-strategy and allows for resources to be diverted to new Districts. Nevertheless, as the blog points out, some modest continuing technical support after the formal exit, perhaps utilising a peer district system, is likely to support sustainability and improvement.

Geoff, thank you for explaining the detail in a cascade approach. I note in the Independent Completion Report for the project you describe, the outstanding AusAID Indonesia-Australia Basic Education Partnership, that this approach was very positively evaluated indeed.

As educators, we could analyse to the advantage of improving project impact, why it is that such good practices often seem to get lost in subsequent projects. My hunch is that during project design and implementation stages, the time pressure on donors, contractors and advisors alike lead to surface approaches in much the same way that examination pressure leads to surface approaches to learning among students.