Like most Pacific Island countries (PICs) Kiribati faces its fair share of development challenges – smallness, isolation, a constrained private sector, high youth unemployment, rampant population growth, a heavy reliance on imports and the list goes on. Alhough Kiribati is unique. Unlike the Melanesian countries to its southwest, as a group of low-lying coral atolls it lacks scope for primary industry development. It also lacks the same access to regional labour markets that the Polynesian countries and its Micronesian neighbors have through access quotas and free association with ANZUS (only 75 I-Kiribati are permitted annually through New Zealand’s Pacific Access Category). On top of this, it is one of the most vulnerable island groups in the Pacific to sea level rises, as Nic Maclellan previously explored in a Devpolicy blog here.

With this in mind, in 2006 the Australian Government offered Kiribati a helping hand. It came in the form of a pilot program providing support for up to 90 students to train in Australia over an eight year period. Why nurses? With an ageing population, Australia was and still is set to experience a severe shortage of qualified nurses by 2025, despite this demand dampening post-GFC. It has also had the added benefit of offering opportunities to I-Kiribati women who face a dearth of education and employment opportunities relative to their male counterparts.

It was a modest gesture on Australia’s part. Even the original design document admitted as much – suggesting that it would increase the employment rate of school leavers by a mere 1.5% annually, not a great deal for a country with a population of 100,000. It was nevertheless welcomed as a chance to start addressing the severe development challenges outlined and diversify the remittance base, which has traditionally been and still remains largely reliant on seafarers.

Fast-forward eight years and 84 students have taken up a KANI award, $18.8 million dollars has been spent and an independent review of the scheme has been released.

Do the benefits outweigh the costs?

The main objective of KANI was to ‘educate and skill I-Kirbati youth to gain Australian and international employment in the nursing sector.’ It’s still a little premature to give a complete assessment given many in the third cohort are still studying, but here’s an overview of the results to date.

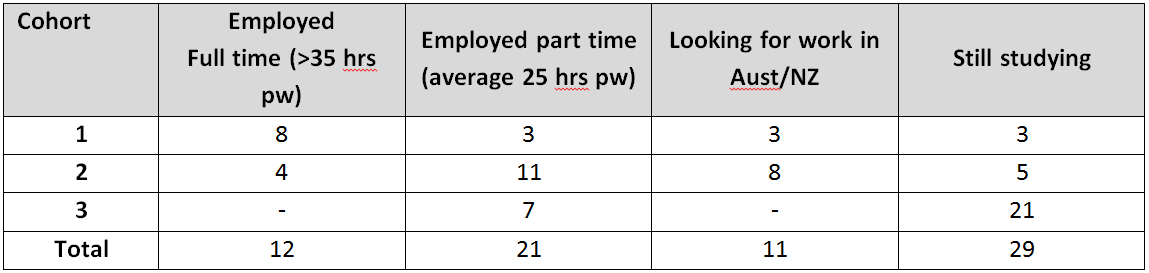

Table 1: Employment status of KANI students in Australia and New Zealand (as of 12 March, 2013)

Source: KANI Independent Review 2014, DFAT

Source: KANI Independent Review 2014, DFAT

Once the third cohort have finished their studies it is expected that ‘sixty eight students will have graduated – 64 as registered nurses, 3 as social workers and 1 with a Bachelor of Human Services.’ The best-case scenario is that all 64 of these will find full-time work as registered nurses in ANZ. This is highly unlikely; however, even if half of these were to find work abroad, the scheme would be substantially more effective in achieving the outcome of international employment than comparative schemes across the region. A mere 1.2% of all Australia Pacific Technical College (APTC) graduates now reside in ANZ, for example. KANI is more successful because they are able to establish connections with potential employers. Graduates intending to stay are able to apply for a Graduate Skilled Migration visa (485) and in the meantime can work full-time on bridging visas. They are supported through this process. With APTC, there is no specific targeting or support provided to access international jobs.

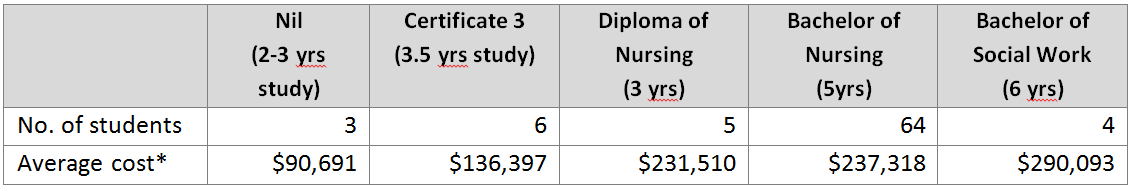

The benefits of these nurses working abroad are clear. Aside from the future income of KANI nurses, there is the likely multiplier and poverty alleviation impacts of remittances and the productivity enhancements of knowledge transfers in the health sector. However, do these benefits outweigh the cost of training each KANI nurse? And the costs are significant. If the total cost of the scheme is weighed against the number of graduates that will become nurses, this equates to approximately $290,000 per registered nurse ($18.8 million / 64 nurses). As the following table shows, the average cost for each qualification is also high. The question must be asked, why are they so expensive to educate?

Table 2: Average cost of a KANI qualification

For starters, Australia is the most expensive country in the world for international study. This certainly doesn’t help, but there are other factors which contributed to the cost blow out. There was an insufficient use of stop/go points in the program. This meant that students who failed subjects were supported in time (and at extra cost) to repeat failed subjects, some 31 students in total. The fact that Griffith University was managing the contract meant there was an incentive to push students through to Bachelor of Nursing Studies as well, given the extra tuition fees obtained from doing so. Furthermore, there have been a disproportionately high number of student pregnancies. In total, ’27 babies were born to KANI female students from 2010 to 2013.’ This compounded the cost per student as ’18 of the 27 students who had pregnancies required extra time for failed or withdrawn subjects and rescheduling of clinical placements.’

Given the associated costs, the independent review determined that under the ‘worst case scenario’ (which it highlighted as the most realistic), the returns from the program are only marginally positive.

What are the alternatives?

KANI is an extremely high cost program especially when weighed against the employment outcomes so far. Part of this came down to the design of the program and the level of student pregnancies, but ultimately Australia is and will remain an immensely expensive destination for tertiary education. How can Australia allocate $2-3 million of expenditure a year to more effectively address the issues Kiribati faces?

There are many options, several of which are suggested in the independent review. The suggestion of increasing places for the Australia Pacific Technical College (APTC) and the Kiribati Institute of Technology (KIT) will not achieve the intended outcome of ‘Australian and international employment.’ As highlighted only 1.2% of APTC graduates successfully migrated to ANZ. The largest underlying issue is the cost of attaining skill recognition, which currently deters APTC graduates. The review recognised this and suggested a logical alternative would be to spend the money furthering APTC links with employers internationally.

The review also suggested increasing Australia Development Scholarship (ADS) awards, but this misses the mark. ADS awards though cheaper than KANI awards are still highly costly. The review itself suggests that KANI students only receive $41,000 in additional support compared to ADS students by one measure. Meanwhile, the suggestion of upgrading the Kiribati School of Nursing to deliver diplomas in nursing to Australian standards is a good one – though the feasibility of this would require a separate study all together.

Other alternatives not mentioned in the review could be to train I-Kiribati nurses in nursing colleges in the broader region. The Philippines is one country which successfully educates nurses in-country to a high standard and has a proven track record of delivering international employment outcomes. Many nurses could be trained in the Philippines for the same cost of training one in Australia. Another option would be to open up a quota for I-Kiribati to immigrate for Australia in the same way that New Zealand has through its Pacific Access Category, offering them the same access to HECS-HELP that Australian students receive.

Should KANI be extended beyond 2014?

KANI is one of the few labour mobility initiatives that has truly delivered on its goal of delivering Australian employment. It would therefore be unfair to write it off prematurely, but the associated costs at present are too high to justify its continuation. For an expenditure of $2-3 million annually, the Australian Government should be able to achieve more than an average of 8 registered nurses per year. Given the severe development challenges Kiribati faces and its current lack of access to regional labour markets, it deserves a cost effective labour mobility scheme that delivers outcomes for many I-Kiribati. KANI points the way forward, but is clearly not the answer itself.

Jesse Doyle is a Research Officer at the Development Policy Centre.

It would be wise to take a closer look at the KANI program. The costs could be greatly reduced if the students didn’t have to complete two courses. Firstly they complete a diploma then a degree. This adds a greater amount of stress, exams and time for the students. Many of the students had the capabilities of undertaking a degree but were not permitted for various reasons. As I supported them through the first years there were many issues that contributed to their failure rates. Many related to the institutional processes. I’m sure that an exit point at a diploma level would decrease the costs and would better suit some students however this option does not allow them permanent residence. Their stipend was excessive in the first instance allowing many students to live in one place pooling money that at one point exceeded my wage. So there are many hidden costs to this program and benefits for those involved who enjoyed frequent trips to the Coral Atolls. Needless to say it should not continue under the same format, it definitely needs some changes.

I applaud the KANI review team on what to me is an accurate assessment of the costs and benefits of KANI. Having had concerns over the high cost of the program vis-a-vis the development returns, I welcome the team’s recommendations to improve effectiveness and efficiency and particularly the recommendation that an assessment be made of other potential options involving working with regionally based institutions. The inclusion of a cost-benefit analysis brings to the forefront a question we need to be continually asking: for the same amount of money should Kiribati (insert any other country you work in) be getting a better return? What other options are feasible for $2-3 million a year? Is this the only way to achieve this objective? We shouldn’t become so wedded to a program that we don’t see the forest for the trees.

I know the Government of Kiribati thinks highly of the KANI program but the opportunity costs involved are accumulating with each passing year. I urge both the Australian and Kiribati governments to consider the recommendations of this review with an open mind to what else is possible that might deliver greater development benefits to Kiribati.

Really interesting post, thanks Jesse.

Your suggestion of training nurses in the Philippines got me thinking. It certainly deserves further inquiry. You say that many nurses could be trained in the Philippines for the same cost of training one in Australia. Do you know the costs of training in the Philippines? And do they train in English or in Tagalog? As if not in English this would raise the costs? Also, in NZ at least, most Filipino nurses still have to go through a basic competency assessment to ensure they reach NZ nursing standards before they can practise. This takes time and money. I’m not sure of the situation in Australia but if i-Kiribati nurses were aiming for the New Zealand and Australian markets, then this would also have to be factored into the overall cost. I’d love to see a follow-up blog post investigating this idea further. I also think the idea of raising nursing training standards in Kiribati (and other Pacific Island Countries) is another idea worth pursuing further, and I’ve heard others mention it too. But for now, thanks for the great analysis of KANI and for some thought-provoking ideas.

Jo,

Many thanks for your comments. I agree that it deserves further enquiry. I spent some time in the Philippines last year studying their nursing colleges. There is obviously a huge degree of variation in the costs of a nursing degree in the Philippines depending on whether it’s public or private, but one year of tuition fees in Australia could in most cases cover an entire degree’s worth of tuition fees in the Philippines. The living costs are also evidently much lower. There are some nursing courses offered in Tagalog, but many are offered in English and to a very high standard. As with NZ, in order to gain entry to Australia they are required to pass a nursing competency test along with an IELTS language proficiency test. This would add to the overall cost, but still amount to a fraction of the average cost for a KANI graduate at present. Given your background as an RN, it might be worth us writing a collaborative blog further exploring this idea.

Awesome, Jesse. Thanks for that. Happy to collaborate on a blog, although I’m not sure what I’d have to contribute without actually doing some research into the issue. Feel free to get in touch via Devpolicy – be great to talk more.

I’d like to respond to Aileen’s comments about Australia Awards, indicating it’s an example of boomerang aid. Although funds are going to Australian universities, I’ve observed that the scholarships provide real and measurable, good development outcomes in most cases. I know women who studied agriculture at UQ, who are now applying what they learnt in the ministry in Baghdad. I know a Samoan woman who studied at Bond Uni, Indonesians that studied in Sydney, a Kenyan lady who studied in Canberra – all of whom have returned to their home countries and are actively contributing to strengthened public sectors. These individual’s stories represent a good investment when compared to the alternatives. As an example, an education at University of Baghdad is unlikely to have produced the same outcome as study within Australia. Part of the scholarship value is also providing an opportunity for future leaders to experience what functioning service delivery looks like – buses that turn up on a schedule, police that turn up to work without taking bribes, road rules that are commonly followed, public amenities, weekly rubbish collection, access to qualified doctors, reliable electricity supplies, hospitals where doctors can only work if qualified, etc. (Things we take for granted.) Then the other longer term benefit of the program is the transnational linkages created and now sustained through the alumni network.

The short term and long term development value received from studying at Australian institutions is the reason for continued commitment to the program, rather than some kind of influence you may perceive Australian institutions have over government.

(On another note, with regard to the length of time for studies, you may find the additional time relates to pre-requisites for bridging programs and academic preparatory studies.)

Hi Jen,

Great response. I am in the midst of a DFAT funded (but independent) study on the impact of scholarships in Africa. And I just got back from some fieldwork in Mozambique. I have been quite skeptical of scholarships in the past (generally agreeing with Anna’s contention that they are of great benefit to Australian institutions and are limited in terms of aid effectiveness) and indeed have written pieces to that effect.

But having conducted this fieldwork, I was very impressed by the impact of so-called “soft skills” as you note. All the alumni I interviewed focused on this – seeing how Australia and Australians worked, expectations, cross-cultural communication, directness, etc. While most of the technical skills could be taught just as well (or close to it) in their own universities, the cultural experience can only really be gained in Australia (at home most would study part-time which would further limit their ability to invest fully in study).

I still think there are things the Australia Awards program can do to get the balance right but I support what you have emphasised in your post.

Joel

Note to Jen – I said nothing about boomerang aid (that was Anna). I was observing that we probably aren’t comparing apples and apples when comparing the Kiribati Nursing program with ADS, and that if we factored in the additional bridging work, the degrees themselves probably have similar costs.

Personally, I don’t believe in the concept of boomerang aid – it’s overly simplistic.

Oops, sorry Aileen. You’re correct, I was referring to Anna’s comment. I am with you – the concept of boomerang aid doesn’t take into account any of the complexities.

Agree with you too Joel, there is a lot of opportunity for strengthening the outcomes for scholarships. But overall, and especially after speaking with alumni, it does seem like a successful development program.

Jesse, fascinating article.

One element that would be interesting to look at is whilst the investment is large, it seems much of the funding is being spent in Australia. This is one of the huge issues with the Australia Awards (Australian Development Scholarships). If the government were to decide not to continue funding the AAs (unlikely), there would be a massive backlash to the decision from universities who appreciate the healthy addition to their funding pool from the fees paid on behalf of awardees. So whilst it is an aid program, it has a very happy domestic constituency. I would guess this program is similar.

Clearly one of the challenges here is also the amount of assistance the I-Kiribati participants need to perform to acceptable standards. To take 3.5 years to achieve a Certificate III – something I understood normally takes six months – means that there is a LOT of work happening prior to the commencement of their studies to ensure they are able to pass – and this is to be expected, the education system in Kiribati not being of a high standard. Your costing may therefore be out if you are comparing it to ADS, where the vast majority of participants are coming in able to study at an expected standard (and where most are quickly sent home when they fail courses). If you factor this additional assistance in, you may find the program more cost-effective than it appears at first.

Just further, I checked and the Bachelor of Nursing at Griffith is normally 3 years full-time, not five years. Even with a year off for children, there appears to be more happening to successfully graduate participants than is usual for a scholarship recipient.