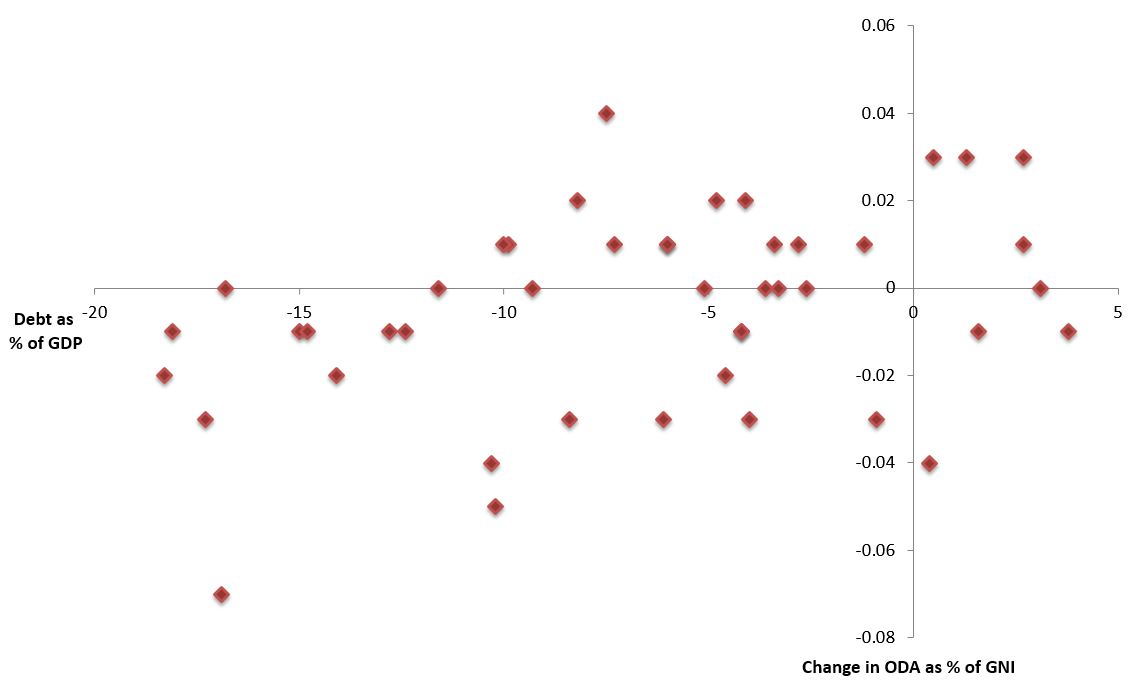

Readily available statistics on Australia’s aid program go back to 1971. Since that time no Australian government has ever increased aid as a share of GNI when Commonwealth net debt has been greater than 10% of GDP. In other words, it is very hard, perhaps impossible, to achieve growth in the aid program when the Commonwealth is seen to have significant debt.

Net Commonwealth debt vs change in ODA, 1972 to 2016

Sources: MYEFO 2015 Table D4, DFAT Aid Statistical Summary Table 5 and aid budget papers

Aid is only a small part of total Commonwealth budget expenditure (the 0.5% of GNI promise would cost just 2% of the Commonwealth budget), however the much higher priority the public and MPs generally give to domestic expenditure and the fact that aid can be cut without Senate approval make cuts to aid a very popular option for Treasurers and Finance Ministers looking for money. This has been shown most recently in the three decisions of the Coalition to cut planned aid by $11.3 billion over 5 years, and much more beyond that. While aid is only about 1% of total budget expenditure it has made up around 25% of total budget cuts announced by the Government for the period 2013-14 to 2018-19.

Australia’s net debt is currently 16.9% of GDP and is forecast to rise to 18.5% by 2017-18 under the Government’s current budget consolidation plan, which is driven by a gradual increase in revenue and very significant expenditure constraint. Under this plan debt will not drop below 10% of GDP before 2025-26.

Taking this into account I would argue that those who seek a more generous Australian aid program need to focus not just on public and MP attitudes to aid, as important as these are, but also help to ensure a broader budget environment that provides some room for supporters in Parliament to increase aid.

This has not been a common strategy for the aid sector. While other advocacy groups such as the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) regularly propose ways to increase revenue or offset their budget proposals (for example see their Budget Priorities Statement 2016-17), almost all lobbying by Australian aid advocates has ignored the larger budget situation and failed to propose offsetting revenue or savings measures.

In the last ten years a structural budget deficit has developed as the Howard and Rudd governments implemented personal income tax cuts, the Rudd and Gillard governments failed to match increased spending with revenue and the Abbott and Turnbull governments have implemented large increases in defence and security expenditure while seeking to reduce overall tax rates. The aid sector has largely been silent on all of these decisions and has not contributed significantly to the current debate on how to resolve the debt situation, despite its clear impact on the scale and reliability of the Australian aid program.

Given the budget imbalance and the Government’s commitment to limit spending, any calls at the present time for aid increases are likely to be significantly strengthened by identifying offset expenditure savings or revenue increases.

However, in the longer term it seems to me that the central threat to achieving more budget space revolves around the Coalition Government’s goal of limiting revenue and expenditure to a maximum of 25% of GDP. This number has been proposed as a critical ceiling for both. In January the Treasurer said “In the last 30 years there has only been one year in which a surplus has been achieved, where expenditure to GDP has been more than a quarter of the economy”. A few days later the Secretary of The Treasury, John Fraser, said “… seeking to keep spending below 25 per cent of GDP may be a useful marker.” Even Labor’s Finance spokesperson, Tony Bourke, has said “historically, broad balance has been when the numbers are around 25”.

The problem is that we are currently spending 25.9% of GDP and this does not include planned increases in defence expenditure, the full NDIS, extra expenditure required for health and welfare due to the ageing of the population, or the shortfall in aid.

It is important to maximise the efficiency of government spending and keep revenue as low as is needed. However, Australia’s health, education and welfare services are already cost effective in relation to most of our peers, so the capacity to drastically cut costs is limited. Of all our OECD peers only Switzerland spends less on government as a share of GDP.

The correct level of revenue should be determined by our citizens’ desires, our nation’s commitments and our need for budget balance rather than some ideological allegiance to a particular size of government. Presently the Coalition argues that we have a spending problem rather than a revenue problem. Labor at least argues we have both a spending and a revenue problem, but so far has failed to spell out how it will fully fund its plans and commitments.

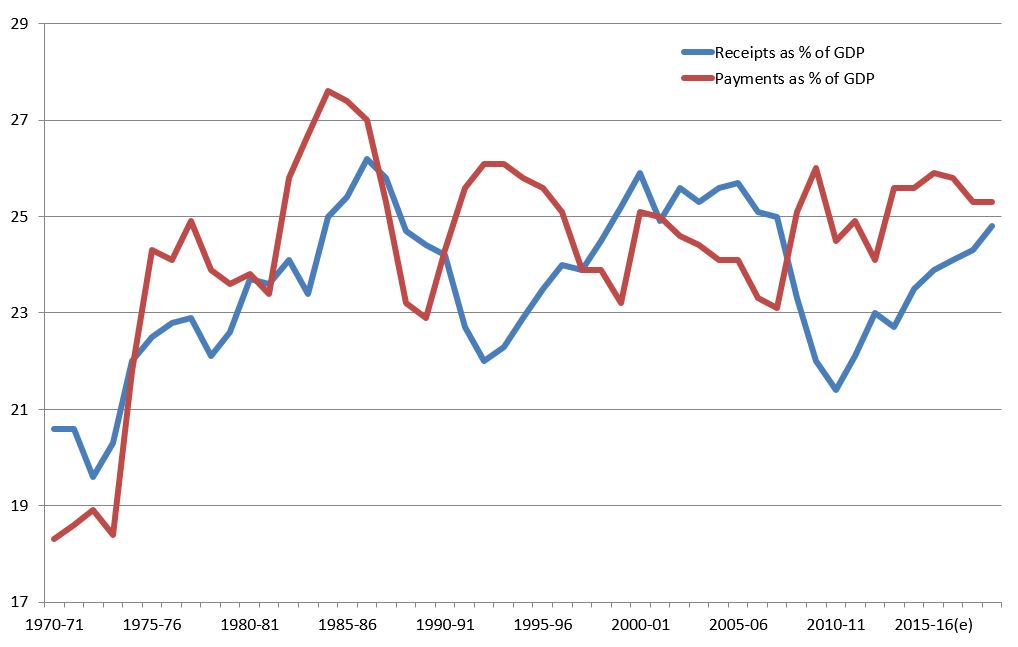

The following chart shows the history of budget revenue and payments since 1970 and summarises the Government’s plan for budget consolidation. It shows just how large the revenue shortfall has been and reflects the Government’s plan to keep both revenue and payments to around 25% of GDP.

Australian government receipts and payments as share of GDP

Source: MYEFO 2015 Appendix Table D1

Implicit in this plan is keeping aid at a very low level. This is also implicit in current Labor plans given they have not yet fully funded their health, education, defence and NDIS commitments and will have to also incorporate debt repayments of 1% of GDP for the foreseeable future.

Unless government is willing to lift revenue, probably to around 26% of GDP, it is very unlikely that aid will ever be significantly increased. Those who believe that Australia should lift the size of its aid program need to be willing to argue for the financial resources to do this. We need to address the bigger picture.

Garth Luke is a consultant researcher and writer on aid and development policy.

Thanks Garth and Bob

We do need new taxes for the 21st century, as the additional revenue paying for the services we expect of Government. Like the three main “cares”: child; health care; aged. Or foreign aid.

An alternative is a new (Tobin) Tax of about 0.01% applied to high-frequency foreign exchange transactions. A year ago, the Chairman of ASIC claimed that “Australia is being picked off by highly-leveraged, online foreign exchange brokers”. http://www.smh.com.au/business/markets/currencies/asics-greg-medcraft-says-foreign-exchange-brokers-are-picking-off-australia-20150322-1m499a.html%5D

The Reserve Bank calculated FOREX trades in April 2013 averaged US$182 billion each day. By contrast, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade reported Australia’s two-way trade in 2012 was $623.8 billion, or about 4 days FOREX trading. This suggests over 90 per cent of these trades are speculative.

A Tobin Tax would mean a possible extra $18 million each day in Government revenue. Taxing the speculators would provide the extra revenue for Australia’s aid budget, e.g. child immunisation, clean water and education.

Thanks Luke. This is a very important and thought provoking piece of work. I would not advise the aid NGOs and other aid advocates to rush into the taxation debate too quickly, but some sober reflections on the data in this article might lead to some interesting options.