On July 6, the Government released its response to the findings and recommendations of the Aid Review. Matt Morris, the Deputy Director of the Development Policy Centre, comments on the Aid Review’s report.

As a former treasury economist I’m always delighted when reviews put numbers around their recommendations. It is good for transparency and brings greater clarity. There’s a lot in the Aid Review report to think about and the panel have made a compelling case on how to spend an increasing aid budget aid wisely. This blog takes a look at some of the numbers in their plan.

How much extra aid?

The Aid Review forecasts that the aid program will increase from $4.3 billion in 2010-11 to $8.0 billion in 2015-16. This is less than our forecast of $8.6 billion and that of AusAID in the 2011-12 budget where the number quoted by Peter Baxter at the lock-up was $8.5 billion for 2015-16. This means that the allocations in the Aid Review’s report, discussed below, are on the conservative side, with perhaps an extra $500 million available for programming in 2015-16 compared to the Aid Review forecast.

Shining a light on global programs

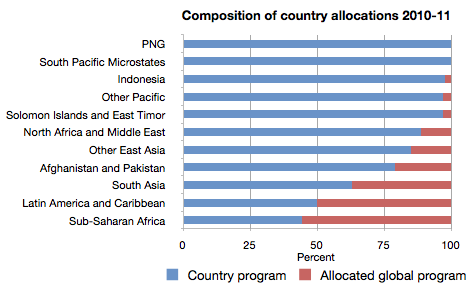

By putting some numbers on how the global program is distributed to countries and regions, the Aid Review has helped to reframe the way AusAID thinks about it’s country allocations. The Aid Review shows that country programs are the dominant form of Australian aid in Indonesia and the Pacific, but that allocated global programs–including funding for the UN, multilateral development banks, and global fund–is a much larger share of country allocations in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

By putting some numbers on how the global program is distributed to countries and regions, the Aid Review has helped to reframe the way AusAID thinks about it’s country allocations. The Aid Review shows that country programs are the dominant form of Australian aid in Indonesia and the Pacific, but that allocated global programs–including funding for the UN, multilateral development banks, and global fund–is a much larger share of country allocations in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Suggesting indicative aid allocations

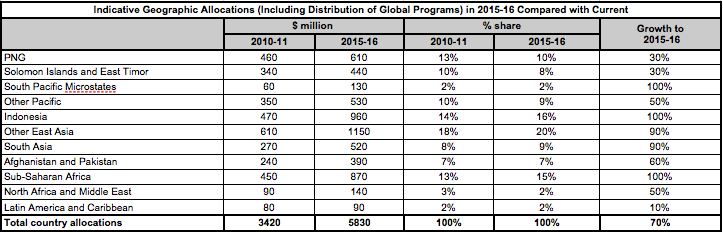

The Aid Review also puts numbers around its recommendations on where aid should be spent. It provides an expenditure framework for the aid program, built on a pragmatic approach to scaling up: more aid for countries that need it and use it well, and a choice between country and global programs based on Australia experience and expertise.

The Aid Review argues that the biggest increases in aid should go to South Pacific Microstates and Indonesia, and Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. In the case of the Microstates and Indonesia, these are countries where Australia has experience and expertise and the recommendation is to scale up bilateral aid programs. In the case of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, these regions account for about two-thirds of the World’s poor so there is a strong case for giving more, yet the Aid Review is pragmatic in recommending that all of this scaling up should be through global programs. That means no further increase in country programs (bilateral aid) in Sub-Saharan Africa–this is a bold, yet practical recommendation, but it remains to be seen if the government will accept it.

While the Government has so far ducked the recommendation on aid allocations–noting that specific geographic allocations will be decided by the Government in the 2012-13 budget process–it has at least accepted that aid to Asia-Pacific, South Asia and Africa will be increased, bilateral aid to China and India will be phased out and any future increase in aid to Latin America and the Caribbean will be modest (with any increases to be provided through regional and global programs).

Improving allocative efficiency: A better budget process

The Aid Review also argues for better budget numbers. An important recommendation (number 25) from the Aid Review is that the Government should develop and implement a Cabinet-endorsed four-year strategy for the entire aid program, for policy and funding clarity. And it is a major achievement that the Government has agreed to develop a comprehensive aid policy framework, linked to a four-year budget strategy, which would be a rolling strategy.

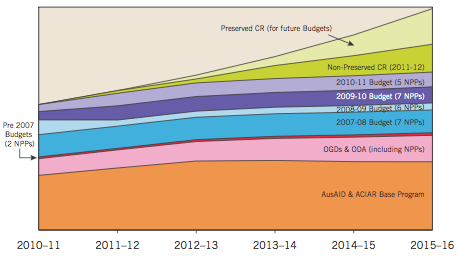

This is good news for several reasons. The old approach of new spending initiatives, led to a layering of new programs on top of old ones and a fragmentation of aid–it was an inefficient, non-transparent way to allocate total aid and undermined scrutiny of the base program (see chart). The new approach will enable the government to make strategic choices across the entire aid program. It will also make aid more transparent and enable better scrutiny where money is going and why.

This is good news for several reasons. The old approach of new spending initiatives, led to a layering of new programs on top of old ones and a fragmentation of aid–it was an inefficient, non-transparent way to allocate total aid and undermined scrutiny of the base program (see chart). The new approach will enable the government to make strategic choices across the entire aid program. It will also make aid more transparent and enable better scrutiny where money is going and why.

Improving administrative efficiency

Parts of the aid program, based on many accounts, are already very stretched. The Aid Review recommends that administrative costs will increase from $250 million in 2010-11 to $400 million in 2015-16: a 60% increase, but less than the overall increase in aid. That means there will also need to be productivity gains, which should come from economies of scale. Throughout the report, the Aid Review recommends ways to do this: it stresses the need to geographically focus the bilateral program (recommendation 14), make more use of multilaterals (recommendations 5 and 15) to select fewer sectors (recommendation 8), and to streamline processes and reduce paperwork’ (p29). So if the aid program can become more disciplined, then AusAID and other government departments won’t have to stretch so much.

Final thoughts

The Aid Review panel has done an excellent job. It’s recommendations are grounded in theoretical and empirical evidence and best practice among donor agencies. And it has provided a considerable body of analysis that policy-makers and aid officials will now need to chew over and digest. There is a lot to do, not least to flesh out the four-year strategy and budget, but the Aid Review’s solid analysis and recommendations gives confidence that aid can be doubled and spent well–it’s now up to the Minister and aid officials to deliver.

Matt Morris is the Deputy Director of the Development Policy Centre at the Crawford School, ANU.

Good numbers, good plan – great summary!

The doubling of the ‘South Pacific Microstates’ allocation is certainly timely and welcome.