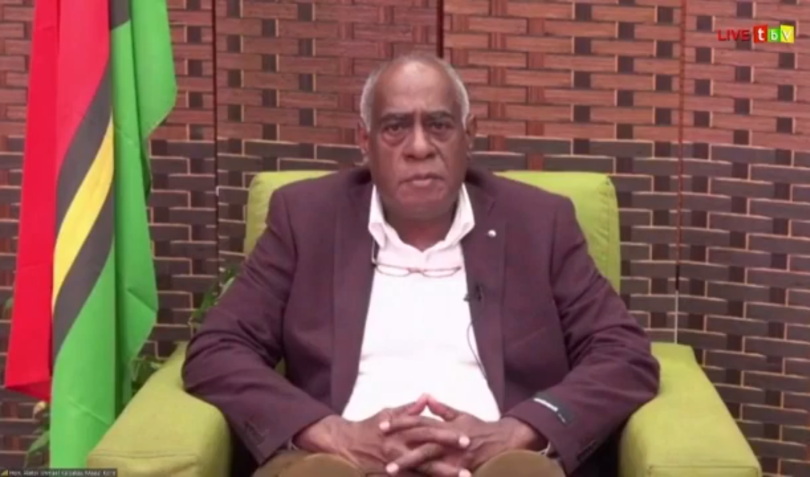

Newly elected Vanuatu Prime Minister Alatoi Ishmael Kalsakau Ma’aukoro of the Union of Moderate Parties (UMP) may have been elected unopposed last Friday, 4 November 2022, but that does not guarantee him success, unless he can maintain the support of all his coalition partners.

His government enjoys a 30-member majority, following the recent snap elections of 13 October 2022 – just 18 months short of the scheduled 2024 polls.

Kalsakau was Deputy Prime Minister in the last government before dissolution, and his new cabinet line-up includes some of that government’s loudest critics – Ralph Regenvanu of the Graon mo Jastis Pati (GJP), who has been made the new Minister for Climate Change, and John Salong as the new Minister of Finance, also from the GJP. Coalition partners include Charlot Salwai’s Reunification Movement for Change (RMC), Leaders Party Vanuatu (LPV) headed by firebrand Tanna MP Jotham Napat, and Sato Kilman’s People’s Progressive Party (PPP).

Mr Kalsakau had resisted calls from former coalition partners – notably Vanua’aku Pati (VP) of former Prime Minister Bob Loughman Weibur, now appointed leader of the opposition – to continue their reign. Had he accepted to move back with all his seven UMP members, it would have been considered a fait accompli. Therefore, it remains a surprise that he shrugged off those calls, opting instead to team up with some of his fiercest rivals.

Vanuatu was forced to return to the polls by virtue of a dissolution of parliament by the country’s head of state Nikenike Vurobaravu on 18 August, after weeks of political wrangling between the government and the opposition which saw 17 members of the Weibur government defecting to the opposition. They had cited dissatisfaction over the prime minister’s leadership on a number of issues.

Therefore, when the country’s head of state endorsed the decision of the Council of Ministers to dissolve parliament, echoes of genuine concerns reverberated all round. Then opposition leader Regenvanu wrote specifically to the head of state, urging caution and for His Excellency, a VP party founder and avid supporter, to tread carefully before bringing down the gavel.

Cost-wise, the opposition had a valid point – a snap election would cost taxpayers more than if there was to be a change of government through a motion of no confidence. Government revenue forecasts were growing bleaker, with projected revenue significantly hit by the EU decision to cancel its visa waiver with Vanuatu.

Earlier, Prime Minister Weibur had resisted a couple of other attempts to dethrone him. It is rare for a leader in Vanuatu to gracefully resign – even for serious misconduct. In 2015, then Prime Minister Moana Carcasses dragged all of his cabinet ministers down, despite facing serious charges of corruption, and held tightly to power until the day Justice Mary Sey pronounced them all guilty and ordered their immediate incarceration. Throwing in the towel too easily is perceived as a weakness.

Prior to the October snap elections, the opposition camped at Island Magic – a secluded resort just 16 minutes drive northwest of Port Vila town – in the hope that Prime Minister Weibur would either resign or face a vote of no confidence. The opposition cited controversial amendments to the national constitution, illegal procurement of a large contract to build an extension to the main referral hospital, and alleged mishandling of cases of senior public servants as key reasons for the motion.

In the run up to the 13 October polls, the former regime banked on certain pre-election promises – the most obvious being that they would continue their rule, when a new mandate had been sought successfully. Call it naivety perhaps, but Mr Weibur and his VP cohorts did not think that Alatoi Ishmael Kalsakau would desert them and pip them to the top job.

Mr Kalsakau, a professional lawyer-cum-politician, had been a trusted ally since 2020. Using his legal expertise and knowledge, Kalsakau was able to guide the Weibur government, often through quite treacherous waters, since 2020 when the 12th legislature was constituted. The global pandemic did not make it any easier.

In June this year, Weibur’s government bizarrely tried to bring about controversial changes to the national constitution under the so-called Eighth Amendment bill. Yet the Prime Minister’s VP party did not fully back the amendments – particularly changes concerning the tenure of the Chief Justice. VP’s open admission raised eyebrows, with many asking “who then masterminded the so-called eighth amendment?”. Normally such major changes go through a vetting process, and as they were quite significant amendments, they would require national consultations.

The controversial changes would have increased the number of ministerial portfolios from 13 to 17, significantly changed who could be considered a citizen, and limited the term of the Chief Justice to a mere five years instead of a lifetime appointment, as has been the case to date. These issues formed the basis for the motion lodged against Prime Minister Weibur.

On the floor of parliament, Charlot Salwai’s RMC teamed up with the opposition to boycott the sitting. They continued their stance thereafter until the bill was withdrawn for lack of adequate support.

There was more that happened under the Weibur-Kalsakau reign. In 2021, in anticipation of a mass hospitalisation if there was a major outbreak of COVID-19 cases, the government bypassed normal procurement processes by awarding a large contract to a local private company to build a massive hospital extension worth almost VT1 billion. The contract could still be subjected to scrutiny. It will be interesting to see how the new government will handle this matter, if questioned by coalition partners.

Kalsakau himself was a former VP supporter – his father George Kalsakau was the first Chief Minister in the former Representative Assembly prior to independence in 1980. He switched his political allegiances in 2015 to contest the seat left vacant by former VP president Edward Nipake Natapei under the UMP ticket, after disagreements with his own VP party’s decision to back rookie politician Kenneth Natapei – son of the late Edward – to run in the Port Vila constituency.

Such power struggles are not new. They are a regular feature of local politics. In addition, over the years leaders have struggled to hold down a stable government – made more difficult by political party fragmentations.

The table below shows the results of the recent polls, and how each of the political parties and groupings fared. Significantly, it demonstrates the enormity of the task at hand for Kalsakau and his deputy, Sato Kilman of the PPP. (As a footnote: the PPP only has two elected MPs.)

As governments are formed more as a matter of convenience and political expediency, rather than on clear-cut policies, there is little guarantee for stability. It is not a surprise that this government has spent almost three weeks at camp since 13 October, trying to flesh out what policy areas they can agree on – at least for the next 100 days in office – most notable of which will be political reform. Both Prime Minister Kalsakau and Regenvanu have come out publicly to reaffirm their commitments to reforms for the better.

The government has at least eight coalition partners. How the new prime minister manages their interests will be key.

Disclosure

Kiery Manassah was a former public relations officer under the Joe Natuman-led government when Alatoi Ishmael Kalsakau was Attorney General.

Leave a Comment