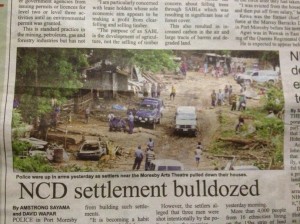

On Tuesday March 12, 2013 a Papua New Guinea (PNG) daily newspaper, The National, carried an article titled ‘NCD settlement bulldozed’. According to the article, over 4000 people’s homes were affected.

On Tuesday March 12, 2013 a Papua New Guinea (PNG) daily newspaper, The National, carried an article titled ‘NCD settlement bulldozed’. According to the article, over 4000 people’s homes were affected.

On that same day, I made one of my regular visits to the Oro/ATS (Air Transport Squadron) settlement in Port Moresby where I have been undertaking field work for the past three months. As I approached the area where my interviews were to take place, I saw one of the community leaders and went to greet him. At the same time, a police car arrived. Rather than going ahead with greeting each other, we both realised the gravity of the visit and as he approached the police, my two companions and I walked quietly away. There were hushed whispers of concern as the news emerged that the police have been sent to advise the community that an eviction notice was about to be issued.

Later that week, I was told that on the day following the interaction I witnessed, the police drove further into the settlement, along the boundary of that portion of land, to advise residents that they must move as they were going to be evicted.

The sudden and violent eviction—using bulldozers and armed police—of the residents of Port Moresby’s urban settlements is not new to the National Capital District (NCD). The State rhetoric surrounding evictions is usually about moving unlawful settlers from State land which has been bought by a private entity or sending a message to settlement dwellers that crime and filth, for which they are often blamed, will not be tolerated.

In 2008 hundreds of people were left homeless when Tete settlement in the suburb of Gerehu was torched and bulldozed after the murder of a prominent businessman in that area. The State was sending a message to the settlement community to stop criminal activities.

In 2012, around 2000 people’s homes were destroyed when another urban settlement, based at the foot of Paga hill, was bulldozed violently when the purported holders of the title tried to evict settlers who have been living there for decades.

The practice of State sanctioned destruction of Port Moresby settlement communities therefore poses a challenge for those interested in livelihood risk and vulnerability in these communities. Development efforts that target sustainable livelihoods are often framed around the management of risks faced by households and communities, exposure to these risks, and the availability and adequacy of coping mechanisms when an adverse event occurs. If using the poverty line as a benchmark, efforts focus on ensuring that people are either lifted above the poverty line, or prevented from falling further below it.

When I ask people who live in the ATS settlement what some of the risks or factors that affect their community as a whole are, and that would have a negative impact on their livelihoods and wellbeing, a common response, inter-alia, is the uncertainty of land tenure and the risk of being evicted.

People recognise that they are not the owners of the settlement land, but many have ended up living there after finding themselves without accommodation in Port Moresby. The very circumstances that have led to their decision to live in the settlement have also meant that they cannot afford to return to their village home.

These responses, along with historic evidence as shown in the above media reports, suggest that State sanctioned eviction and demolition of settlements is an important livelihood risk faced by communities in Port Moresby’s settlement communities. This is consistent with the findings of Chand and Yala (2008)[1].

This has implications for peoples’ livelihood strategies. Dwellings are generally kept small and basic and are overcrowded. Most people start out in shelters built from canvas (tarpaulins) and then build makeshift homes from off-cut timber bought from a timber yard or sawmill. A few of the better off or more confident residents have begun to build large permanent homes. Settlement communities also manage this risk through a number of other strategies such as engaging lawyers, speaking with Members of Parliament in their electorates, and encouraging households to talk to their youth about minimising criminal activity.

With Port Moresby’s rapidly growing population, the high cost of rental accommodation and generally high cost of living, it is likely that, rather than remaining a peripheral part of the socio-landscape, settlement communities will become the norm. Residents of Port Moresby’s settlements are easily among the poorest and most vulnerable in PNG. Their vulnerability is exacerbated by their need for cash to meet daily needs, particularly food.

These issues pose several dilemmas for those interested in urban poverty in PNG. The first is how development actors engage with the State when an important risk faced by urban settlers’ is directly controlled by the State? Second is the need to come to terms with the fact that urban settlements are a norm rather than a peripheral problem. Third is the complication of the discourse on the legitimacy of urban settlement by the broader history of PNG’s land tenure systems. This discourse is nuanced by corrupt land deals, the dynamic between state and customary land, the emergence of land and rental markets within the settlement and the identification of social groups and eligibility of access to land. These are important and they affect peoples’ views and perceptions of their rights, entitlements and the security of their homes.

What’s at stake if these dilemmas are not embraced in the urban development discourse in PNG is far greater than a makeshift shelter. In the absence of all else—State or otherwise—are the threads of relationships between kin, friends and community leaders that are woven to form the fabric that keeps these communities together. This fabric is too often criticised and undermined in the role that it plays in contributing to the NCD. Without it, Port Moresby—notorious as one of the most dangerous cities in the world—would be a far worse place to live.

Every time a community is bulldozed this social fabric—this essence of social protection—is ripped into pieces by the very State that communities look to for support. Its repair and reconstruction is often left to communities to worry about.

[1] Chand, S and C, Yala (2008), Improving access to land within the settlements of Port Moresby, The National Research Institute, NRI Special Publication No. 49

Leave a Comment