I had the honour of working with Brij from 1995 to 1996, when he was one of the three commissioners on the Fiji Constitution Review Commission, chaired by former New Zealand Governor-General and Anglican Archbishop, Sir Paul Reeves. Brij was the local member nominated by the then Leader of the Opposition, and Leader of the National Federation Party, Mr Jai Ram Reddy. Brij brought with him his deep knowledge of modern Fijian political history, but from the perspective of his life experiences to that time.

The other local commissioner was the late Mr Tomasi Vakatora Snr, who came to the Commission after a long career in the public service, as Speaker of the House and a government minister. Mr Vakatora was the nominee of the then Prime Minister, Mr Sitiveni Rabuka. As he had always been at the most senior level of government during my career, he was always “Mr Vakatora” to me. Brij on the other hand was closer in age and less formal, and insisted on being called by his first name.

I returned from study in Boston to join the Commission as its local legal counsel, the other counsel being the experienced constitutional drafter, Alison Quentin-Baxter of New Zealand.

Prior to joining the Commission, I was well aware of Brij and his accomplishments as a historian. I remember quoting many of his sentences verbatim in one of my university essays on Fijian politics and law, because I could not find a way to summarise his ideas as elegantly as he had expressed them.

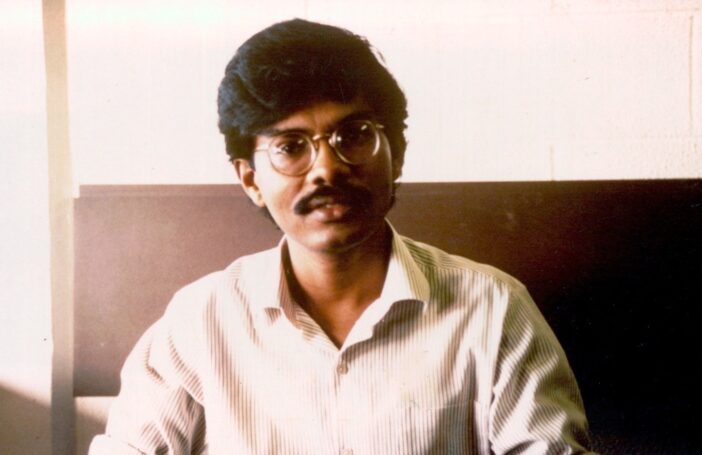

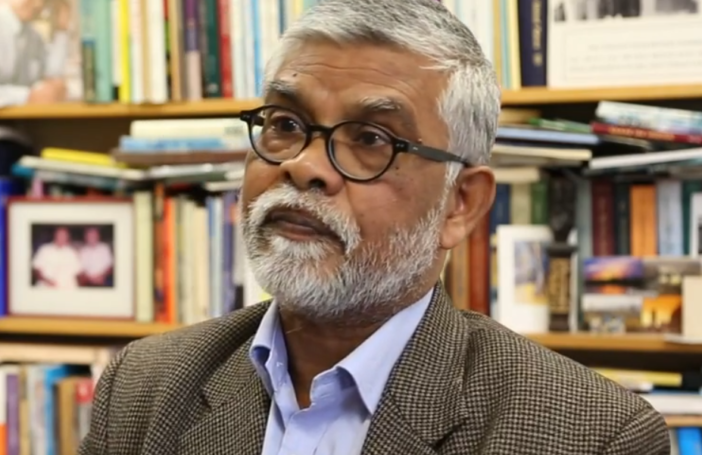

For someone with an established reputation as a formidable academic, Brij was easy to get along and work with, despite the heavy and stressful responsibility of his role. One of his earliest remarks to me was that as a historian, he was excited at the prospect of making history. He spoke of how he sometimes found it hard to believe that he had come from his little village of Tabia in Labasa to such an important national role.

The Commission was established to review and make recommendations for changes to the 1990 Constitution, which was decreed after the 1987 coup. The 1990 Constitution contained various provisions aimed at guaranteeing what was then known as the paramountcy of Fijian interests. These included a House of Representatives elected exclusively on communal lines, with a fixed majority of indigenous ‘Fijian’, Rotuman and ‘General Voter’ seats and a fixed minority of ‘Indian’ seats. It also provided for an appointed Senate, also with a fixed majority of Fijian representatives. The question for the Commission was whether these kinds of arrangements should be continued or replaced by something else.

Brij began his work with the Commission with the clear idea that these provisions should be replaced, ideally by an open system of voting based on a common roll for all. Mr Vakatora, for his part, started with the view that the 1990 arrangements should be retained in principle, and that any tweaking should be aimed at strengthening Fijian paramountcy.

Alison and I were available to the commissioners for private chats to help them understand the legal issues and formulate their ideas, and these positions came through clearly in the early stages of our work.

The Commission’s work involved travelling the length and breadth of Fiji to hear the people. We also travelled all around the world, consulting with experts on governance in diverse multi-ethnic countries, and consulting with experienced leaders and politicians in those countries.

It is to his great credit that Brij approached the task with the utmost dedication and the open mind of an academic. He listened carefully to the people. He questioned the experts closely, and he began to see things differently from how he had seen them when he started.

Sir Paul recognised early on that Brij and Mr Vakatora were proxies for the Indian and Fijian communities, and any accommodation between the communities had to begin with Brij and Mr Vakatora. Brij recognised this too, as did Mr Vakatora, eventually. Fortunately, they were both amiable personalities. A close friendship slowly developed, and over the course of our travels, hearings, and the many meetings, each came to see the perspectives and the fears and hopes of the other community as real and deserving of respect.

They began the journey that we all must travel.

It is fair to say that Brij was the one who brought the energy and academic rigour to the Commission’s deliberations, and his tenacity and enthusiasm must be credited with moving Mr Vakatora to the middle ground represented by the Commission’s report.

Reaching that middle ground took longer than expected. Alison and I were tasked with drafting the Commission’s report against a fast approaching deadline. Being the elegant writer and perfectionist that he was, Brij scrutinised our drafts closely, suggesting or demanding rewrites where I was not able to capture the essence of an idea as eloquently as he would have. He was not prepared to put his name to anything that was below his high standard. Those days and nights were long and tiring. Brij, the hard taskmaster, nevertheless supervised my work in a kindly, jovial way.

By the end of the process, Brij was proud not just of the report and its recommendations, but also of the new perspectives that he had gained from the journey.

He had learnt that power and responsibility look quite different when you move from the seat of an outside critic to the hot seat of a decision-maker. He learnt that perspectives, insecurities and hopes that you do not share, must still be acknowledged and addressed. He was proud of the history that the Commission, and his friendship with Mr Vakatora, was making.

The 1997 Constitution which resulted is of course now history itself. I leave it to the social scientists to discuss whether this was because of flaws in the Commission’s recommendations, or other factors such as the changes that parliament made when adopting the recommendations – for example, the Constitution required a multi-party cabinet, which the Commission had recommended against; it also reversed the recommended ratio of reserved to open seats.

As we all know, Brij and Padma were exiled from Fiji in 2009 after a radio interview he gave to Radio New Zealand which was critical of the military takeover. Sadly, he was never to return to his beloved village of Tabia, in Vanua Levu.

Equally sad is that after the 2009 takeover, the history that Brij had spent his life documenting and the history that he helped to make, has been effectively erased from the national consciousness. Pre-2006 is now prehistory. That long history – the colonial experience, independence and the period thereafter, and the Constitution review – is no longer talked about, no longer remembered. Many young people are not even aware that it happened.

Brij passed away the day before another leader, Archbishop Tutu of South Africa. Tom Vakatora Jnr shared on Facebook a photo of his father, Brij and the Archbishop taken at the latter’s home in South Africa when we went there to consult the country’s leaders about their post-apartheid constitution-making and experiences.

The photograph brought back fond memories of that time. It also brought home to me the similarities between the two men, and the tragic contrasts. Both were champions of equality and human rights. Both were fearless advocates. Both witty, boyish and cheeky and as they appear in the photograph, with a twinkle in their eye.

Mostly though it brought home to me the tragic contrast. One passed away a celebrated leader, at his home in his homeland. The other, in exile far from his beloved Tabia, celebrated all over the world as a scholar but all but forgotten in his homeland.

The challenge for us is to rewrite our history again, to remember and properly honour once more, Brij and our many, many other leaders who have contributed to our national life over our history.

Rest well Brij. Padma and family, may you also find comfort in this sad time.

This is an edited version of the author’s address at a memorial gathering for the late Professor Brij Lal in Suva on 30 December 2021. This is the third of a series of tributes to him, collated at #Brij Lal.

Jon Apted says this: ‘The Commission’s work involved travelling the length and breadth of Fiji to hear the people.’

In a politics class at USP, as a new lecturer starting work just before the 1999 election I repeated the claim that the Commission had travelled and consulted widely, which if I recall accurately came from one of Brij Lal’s essays on the Commission. A Taukei student laughed loudly and in a derisory tone. He claimed that the Commission’s visit to his village was brief, involved speaking with the chief and a couple of elderly (males), then leaving. No `commoners’ and just `important people’. That is, for the people who held power in Fiji it was merely ritualised acceptance of a shallow process.

Significantly what Brij Lal called the best constitution Fiji ever had, had little political weight. It had negligible importance, and lasted only a year or so before being confined to the dustbin of Fiji’s history by a nationalist rabble led by some disgruntled soldiers and a failed businessman. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, as Jon Apted says, the Constitution is pre-history in today’s Fiji.

A very good article. Very well written and quite factual too. Especially the part about pre-2006. That’s history now and the new / next generation won’t have an inkling of whatever really happened and has been happening since 1987. Today most Fijians I meet don’t even know Fiji was a British Constitutional Monarchy from 1970 to 1987 and that even after independence, the Queen remained Head of State just like Australia and New Zealand and that Rabuka removed the Governor General, the Queen’s representative and made Fiji a Republic without a referendum and in the process created the coup culture that exists today. Today’s generation blame everything on the current government because that’s all they have seen and known and they don’t even bother to read the entire book. They’re just reading the recent chapters and judging the entire book based on them.