Sorcery accusation-related violence is a highly topical and sensitive subject in PNG at present, with a range of leaders publicly condemning the practice. The government approved the Sorcery National Action Plan in 2015, and in 2017 allocated significant financial support to the Department for Community Development for awareness programs to counter this type of violence. The harmful practices associated with beliefs in sorcery and witchcraft – including accusations and related violence – are also increasingly being recognised as major human rights violations by a range of United Nations agencies.

Whilst there is a general consensus that awareness and training are important in addressing these issues, both nationally and globally we are just at the start of the process of developing an evidence-based approach to such programs. From five years of working in this area in PNG, and most recently as participant observers in a two-day training program run for police from three Highlands provinces, we would like to share some lessons with others working in this field, to grow the evidence base in a collaborative way. In particular, we address four challenges: differentiating concerns about sorcery from those about sorcery accusation-related violence (SARV); managing participants with different cultural traditions of witchcraft and sorcery; clarifying the legal position in regard to SARV; and ensuring relevance of training after the participant has completed the workshop. This post addresses the first of the four, about which we have the most to say; the next in this two-part series addresses the final three.

As a general introductory remark, it is important to be specific about the objectives and scope of any training or workshop in this area. There is a large range of potential objectives: basic knowledge transfer about state law and procedures; referral pathways; and more conceptual aims that seek to encourage reflection on topics, such as the nature of evidence and proof, causes of sickness and death, personal assumption of responsibility for personal and professional shortcomings and ways of responding to shame and jealousy (all of which are implicated in sorcery accusations).

Differentiating concerns about sorcery from the issue of sorcery accusations and related violence

A fundamental difficulty in training and awareness programs about sorcery accusations and related violence is that many of the participants view the problem of sorcery as being a more significant problem, or just as significant a problem, facing society as SARV. This viewpoint is frequently highlighted in letters to the editor and articles in the local newspaper, and was aptly summarised in the opening to the recent police workshop by a government official who stated “We cannot deny that sorcery and witchcraft is there… You and me we cannot see it but we know that something is happening. The people who are taking violence into their own hands because of sorcery and witchcraft, we cannot deny that they are wrong, but you know they are frustrated.”

Our experience suggests that concerns about sorcery need to be acknowledged and taken seriously in any awareness and training, rather than being swept aside. As participants in training and awareness programs regularly observe, the vast majority of Papua New Guineans believe in sorcery. At the same time, it is critical that the focus is not shifted from SARV, or that any of the messages about SARV are undermined by acknowledging concerns about sorcery.

There are a range of strategies that can be used to meet this challenge. First, it is important to be clear about terminology – the term “sorcery accusation-related violence” can ensure precision about exactly what is being addressed.

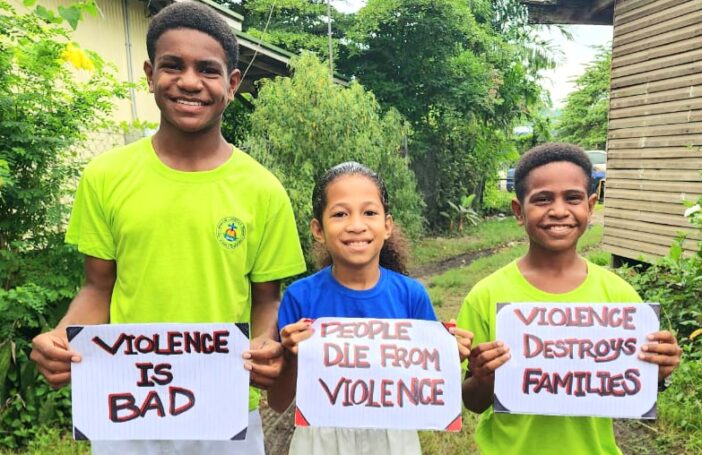

Secondly, it can be helpful to set out some examples of SARV and the impact it can have on individuals, families and communities. First-hand experiences by survivors can be very powerful in raising awareness of the scope of the issue, and there are increasing numbers of audio-visual resources available. Focusing on the suffering of those falsely accused of sorcery, and their families, can be a useful way to cut through attempts to justify these practices on the basis of culture or tradition. If questions of how one differentiates a false accusation from a justified one arise, this can be an opportunity to discuss different types of evidence and the credibility that different types of evidence have. It can also be helpful to give examples of cases where accusations of sorcery are motivated by ulterior motives such as wanting access to the accused person’s land.

Third, a discussion about worldviews can also be of assistance, drawing out how people tend to think differently about the issues when approaching them from a scientific position or a Christian position or a cultural position or even a legal position. Getting people to reflect on the ways in which they themselves navigate between these different worldviews can assist in separating anxieties about sorcery from the issues surrounding SARV.

Fourth, it can be helpful to distinguish between people’s beliefs per se, and the way in which people respond to those beliefs. In other words, a useful message is that whilst people are free to believe in the power of sorcery, this does not entitle them to engage in violence or defamation against a particular individual. It may be useful in a workshop to have a session where participants discuss how concerns about sorcery are able to be dealt with in non-violent and non-stigmatising ways, such as through facilitated dialogue, prayer, and/or accessing good explanations about sickness and death, which are often key triggers for sorcery accusations. Of course this is not to say that any of these strategies are always effective, alone or combined.

Finally, if the training or awareness is with state officials or leaders, such as village court magistrates or police, it can be useful to reflect on the participants’ roles as duty bearers, and the importance of separating beliefs from professional responsibilities.

It is critical that facilitators themselves model the use of correct terminology and resist the temptation to recount stories or anecdotes that turn the attention away from SARV and to sorcery itself, or to allow participants to do so. This is more challenging than it sounds and will need deliberate attention in program development.

The sequel in this two-part series will discuss another three challenges for training in and awareness of sorcery accusation-related violence. A combined version of the two posts is available here.

I come from a Society where Sorcery & Witchcraft accusation is widespread and quite dangerous, where no one would like to stand up and fight the fight to bring change to the Society, therefore, please do sign me in your fortnightly newsletters. Thank you and God Bless

Sorcery Accusation Related Violence (SARV is a major problem facing individual members of the Community in PNG. The Accusation usually involves immediate family member, people in power and standing in the community- Religious Leaders, Educated persons, and Community leaders. We should take certain steps to addressee SARV cases at the first stage of SARV which is the ‘Accusation Stage’.