This is a guest post by Chris Roche of Oxfam Australia.

This is a guest post by Chris Roche of Oxfam Australia.

Recent posts to this blog have focused on transparency, social accountability and bottom-up demand for better governance and in particular the importance of improving the feedback loop from, and the voice of, those people that the aid system is meant to benefit. They have largely focused on why these things are important, and how they might improve the effectiveness of aid.

What they have not really explored is why – if these things are self-evidently good – development agencies don’t seem to be embracing them more fully. This post tries to offer some explanations for this based, in part, on some research on this issue in international NGOs done for the Australian Council for International Development (ACFID).

The first, and perhaps most obvious, reason is that staff in aid agencies – and senior staff in particular – listen to powerful stakeholders who can strongly sanction their behavior i.e. Ministers, the media, Treasury offices, National Audit Offices, etc.

Secondly, these staff (and those more powerful stakeholders) tend to have a dominant view of accountability which is based on a principal-client or contractual model. This is premised on a notion of predictable cause-effect relationships whereby people are held to account for achieving mostly pre-determined activities and outputs, rather than for outcomes and impacts.

Thirdly, other notions of accountability such as social or political accountability, which might be more appropriate to ‘wicked problems’ and complex environments made up of multiple actors, are either poorly understood or not considered as a legitimate basis for ‘evidence-based’ assessment.

Fourthly, although there is evidence that individual initiatives can make a significant and cost effective difference to people’s lives, the evidence that is available is patchy on whether these approaches overall actually make a difference. The authors of the study above note that this is partly because it is methodologically very challenging to evaluate these processes, and their success is highly location-specific.

It would therefore seem that in practice the incentives within agencies are focused on those things that a) are relatively easy to measure, b) are more immediately attributable to staff actions and what managers can more easily monitor (such as disbursement, reporting schedules etc) and c) allow senior managers to answer the kinds of questions more powerful stakeholders are likely to ask.

This suggests that if an ‘unproven’ idea – even if relatively obvious – is hard to measure in the kinds of ways that the powerful prefer it is unlikely to gain traction until something changes.

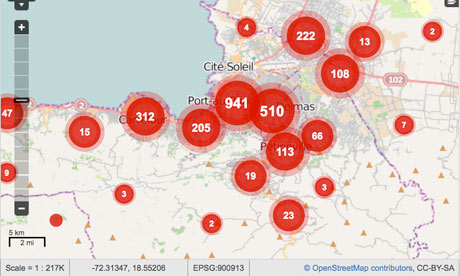

Arguably that change is happening. Despite the reservations about clicktivism, it is clear that the ability of the communities that aid is meant to benefit to tell their side of the story is evolving rapidly. There are also a number of initiatives emerging that are improving information flow to – and from – these communities and crowd-sourcing is emerging rapidly as a way of aggregating these information flows and initiatives. (For more on crowd-sourcing also see the video on Ushahidi below.)

Arguably that change is happening. Despite the reservations about clicktivism, it is clear that the ability of the communities that aid is meant to benefit to tell their side of the story is evolving rapidly. There are also a number of initiatives emerging that are improving information flow to – and from – these communities and crowd-sourcing is emerging rapidly as a way of aggregating these information flows and initiatives. (For more on crowd-sourcing also see the video on Ushahidi below.)

It is a small step from here to building new connections between the ‘recipients’ of aid and tax payers in developing countries. That ‘short route’ of accountability could put all sorts of new pressures on the aid system to reform itself, and could change the power to sanction dramatically!

Chris Roche is the Director of Development Effectiveness for Oxfam Australia.

Thanks Chris – great post, and I definitely agree that we need to move beyond making the case in these areas and starting to actually examine why the changes we’d like to see aren’t taking place.

Your point that – ‘The first, and perhaps most obvious, reason is that staff in aid agencies – and senior staff in particular – listen to powerful stakeholders who can strongly sanction their behavior i.e. Ministers, the media, Treasury offices, National Audit Offices, etc.’ – is a good one. To that I’d add that in many way’s this is understandable. Despite the power of the chequebook, aid agencies aren’t omnipotent (in fact they are often surprisingly impotent when push comes to shove in recipient countries) and they do need local interlocutors, so in a sense it makes sense to work with powerful ones. This is, of course, problematic though. And I don’t think it fully excuses things such as agencies’ failure to divulge information on what they’ve donated to the citizens of aid recipient countries.

I also think that another reason why too little real transparency work happens is simply that most donor agency staff are flat-out busy most of the time, and don’t have enough time to consider new initiatives or undertake activities that might be quite time consuming at least in their set up. This is another example of the negative impacts of what I call the ‘fallacy of low overheads’ (i.e. the mistaken idea that having overheads which are as low as possible is actually a good thing).

cheers

Terence