As part of its tenth anniversary, we collaborated with Femili PNG to produce a report using the client data the organisation has collected since its inception in 2014.

Survivors of family and sexual violence who turn to Femili PNG are categorized into four groups based on the abuse they have endured: intimate-partner violence (IPV), non-intimate-partner sexual violence, child abuse, and sorcery-accusation-related violence (SARV). The great majority of the 7,167 clients Femili PNG has tried to assist between 2014 and September of this year are IPV survivors: 81%. Another 3% have suffered sexual violence inflicted by someone other than their intimate partner. Only 2% are SARV victims, but the numbers are as high as 15% in our Goroka Case Management Centre. The remaining 12% are child abuse victims.

This corresponds to the child-adult split in the Femili PNG client base. 83% of clients are female adults, 5% are male adults; 9% are female children and 3% male children.

Children are only 12% of the client base, but they are especially vulnerable and child abuse cases particularly difficult to resolve.

On average, Femili PNG receives nine or ten new child clients a month. Three or four of them find their own way – often brought by a caring relative – to our doors. Others are normally referred to us by the police or through a wide variety of other channels.

40% of the child clients are aged ten or under. They report a wide range of (often multiple) types of abuse. 57% report being at the receiving end of verbal or emotional abuse; 47% report physical abuse; 31% neglect; 27% rape; and 24% sexual abuse. 73% report previous incidents of abuse (prior to the one that brought them to our doors).

Child abuse is inflicted by a wide variety of perpetrators. In six out of ten cases, the perpetrator is the parent or guardian; in two out of ten it is either another family member, or a family friend; and in the remaining two it is either an intimate partner or a relative from outside of the immediate family. In 77% of child abuse cases, the perpetrator is male, but in 23% it is female.

Femili PNG rates particularly serious cases as high risk: 22% of cases involving adult survivors are thus rated, but 35% of cases where child survivors are involved.

Femili PNG interacts with children not only as clients but as dependants of adult clients. Two-thirds of our adult clients have dependants, who are directly impacted by the abuse their parent or guardian has suffered. For example, children will often have to move into safe house accommodation with their abused parent.

One of the main services Femili PNG provides is to support its clients with emergency (safe house) accommodation. It operates the Bel Isi Safe House in Port Moresby, and works with partners in Port Moresby, Lae and Goroka to facilitate usage by clients of their safe houses (for example, by covering food costs). Femili PNG supports 21% of its adult clients with safe house accommodation, and 41% of their child clients. On average, on any given day Femili PNG now supports 86 clients and their dependants in emergency accommodation. The majority are actually children: 53 versus 33 adults. 14 of the 53 children are clients, and the other 39 are dependants.

The typical adult client stays in a safe house for 22 days, but the typical child client for twice that long, 46 days. This speaks to the difficulty of resolving cases involving children.

It also speaks to the difficulty of running a safe house. Femili PNG systematically collects feedback from its clients (which we have also summarised in another recent report). Most of the feedback is positive, but one common complaint is about the difficulties posed by the number of children in safe houses. This feedback comes both from clients with children and those without.

In some cases, the best solution for a survivor is to be relocated away from where they have suffered from or are at risk of abuse. It is expensive, and it has to make sense for the client. Only 5% of clients are relocated. However, it is much more prevalent with children than adult clients. Only 3% of adult clients are relocated, but 16% of child clients are. Again, as with safe houses, including dependants, more than half the people Femili PNG helps to relocate are children.

In summary, while children may only be a relatively small proportion of the Femili PNG client base, in fact there are as many if not more children receiving Femili PNG’s services and support as there are adults.

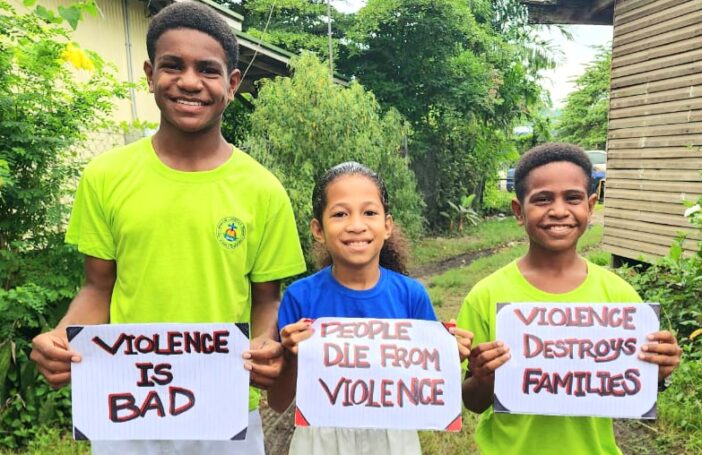

Clearly, more attention is needed to the plight of children when we think about family and sexual violence in PNG. Given the underfunding across the board for services assisting survivors of family and sexual violence, it is hardly surprising that government support for children who have suffered abuse is lacking. There are, however, dedicated child protection officers as well as police and court officers who are working hard under trying conditions to help make a difference.

Encouragingly, the issues facing child abuse survivors are receiving more attention now. Reform priorities currently under discussion include not only more child-friendly spaces at safe houses but also more coordination among the different actors involved. Femili PNG is currently working closely with UNICEF and the National Capital District Commission and is looking forward to progressing reforms and trialling initiatives with them and other partners in this critical area.

The two reports Survivor data from Femili PNG’s first decade and Feedback from survivors: Femili PNG 2021 to 2023 are available for download on the Devpolicy website.

Excellent piece on an important issue, and congrats again on the report and use of this excellent data.

I am struck that this is also just so important to consider in the context of thinking through potential child impacts of parents away in labour mobility programs. The tragic reality seems to be that the baseline levels here, in several countries, is really high regardless of migration status (as always, we need good and credible counterfactuals to talk about any effects/impacts).

While the PNG DHS does not cover child treatment other than indirectly through health and other indicators, MICS surveys have specific questions around certain dimensions of issues and paint a similarly grim. In Vanuatu, 2023, 88% of children 1-14 experiencing any violent discipline method and 84 percent psychological aggression. In Fiji in 2021, 81 percent and 65, respectively. And more than half of the respondents think kids need to be physically punished (slightly higher for men). In Samoa in 2019-20, the figure is 91 percent and 83 percent, respectively, with 80 percent justifying it (slightly higher for women this time). In Tonga, 87 and 73 percent in 2019 but just 37 percent justify it. I wonder what these figures might look like for PNG, although hard to see them get much higher than already listed above.