When looking at the multiple challenges many developing countries face, it is easy to think that any aid is good aid. This thinking underpins donors’ desire to use aid to achieve their ‘close’ geopolitical, commercial and security interests: ‘any aid will help, so why not get some short-term domestic benefit too?’. At a cursory glance, it seems like everyone can win.

Yet, from over seventy years of experience, we know that doing development properly is simply not that simple. Aid dollars are scarce, achieving development outcomes difficult. For these reasons, decisions about how to spend aid have to be carefully considered. This includes analysing opportunity costs. If aid gets spent on x, it does not get spent on y. This blog works through one example of potential opportunity costs to women and children, arising from the decision to spend aid to advance New Zealand’s commercial interests, while also assisting dairy farmers in Myanmar.

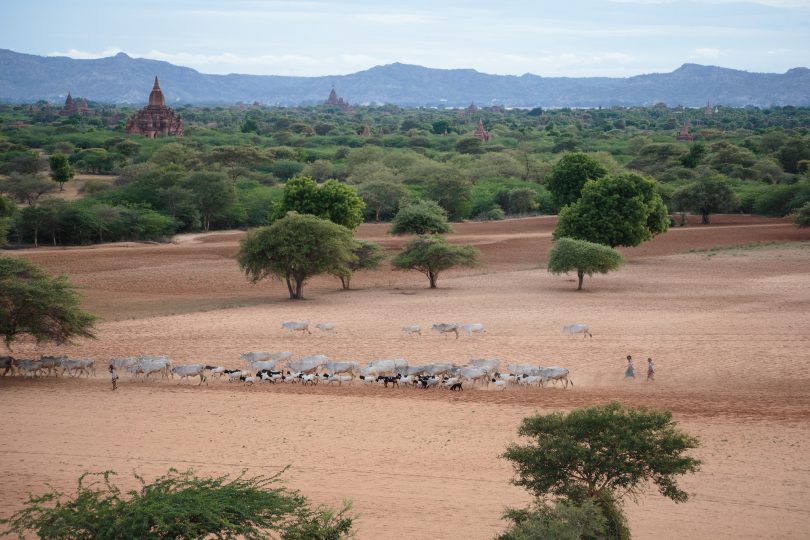

In 2012, the New Zealand Government Aid Programme decided to implement an agricultural project in Myanmar. The funding was to be given in the broader context of ASEAN ‘agricultural diplomacy’, the overall purpose of which was to support growth and development in selected ASEAN countries, including Myanmar, through providing relevant New Zealand agricultural expertise, and therefore increasing linkages between New Zealand and ASEAN agricultural agencies, organisations and businesses.

Alongside potential development gains, the scoping document for the Myanmar agricultural project examined what New Zealand was good at and had a competitive edge in, opportunities for New Zealand businesses or organisations, and areas where New Zealand would receive recognition for its work, have a niche advantage, skills and experience, and could make an impact (p. 5). The scoping document identified activities, such as investing in fruit and vegetable value chains, or apiculture, that had potentially solid development outcomes in the short to medium term, including substantial employment opportunities and poverty reduction amongst landless farmers.

What was finally recommended was investment in small-scale dairy farming, despite the fact that “[d]evelopment outcomes and impacts will be limited to a relatively small number of relatively well-off direct beneficiaries in the short-term, until scaling up occurs…” (p. 2). The project invested NZ$5-6 million over five years, for 20-25 local farmers, each with ten cows – a total of 250 cows. This works out to cost approximately NZ$48,000 for each farmer each year: $4,800 per cow, per year.

The development impacts identified from this project included potential longer-term employment opportunities along the value chain. In the shorter-term, increased milk yields were anticipated, supported by animal health and husbandry training, and Government of Myanmar food safety improvements. Increased milk yields would presumably translate into more income for the farmers, and eventual expansion of the dairy sector. (Milk consumption in Myanmar was noted to be low, and activities were required to expand demand for milk products.) The project has altered its model since conception, now conducting outreach to more farmers. What is under scrutiny here, however, is the initial decision-making process.

The decision to fund 25 relatively wealthy farmers was not based on a country strategy or analysis of the needs in Myanmar, nor was it predicated on a prior aid relationship. Before this, New Zealand provided humanitarian assistance, funding to regional mechanisms, and small, local initiatives (Asia Strategy, Sept 2004). There was no country plan or joint commitment for development between New Zealand and Myanmar. Also, at the time, there was no New Zealand presence in Myanmar, although a post was established in 2013 and an embassy in 2014 (here).

After several years of implementation, no doubt the project has made some positive contributions to development outcomes. But, the decision-making question is: what was the opportunity cost of this decision? What other opportunities for investing New Zealand funds existed, and could they have had a more significant impact for those with greater needs? To explore this question, I use the example of women’s and children’s health.

The New Zealand Aid Programme prioritises maternal, child and sexual and reproductive health in its ‘International Development Policy Statement’ (p. 7). Myanmar has high maternal and infant mortality when compared to the Southeast Asian average (UNFPA). Every year in Myanmar, 2,800 women die due to complications of pregnancy and childbirth. [In New Zealand 11 women died from similar causes in 2015 (p. 12)].

What we know about investing in maternal and child health is that it has significant positive consequences for individuals, their families, and broader economies. Women who use contraception, and get basic health services when they are pregnant, not only survive, but also tend to have increased earnings. Further, both women and children are more educated when women use contraception, and when both receive basic maternal and newborn health interventions (Adding it Up 2017). Empowering women to have only the number of children they want can also have substantial positive impacts on macroeconomic growth (here).

Guttmacher calculates the cost for fully meeting women’s and children’s needs for both modern contraception and maternal and newborn care at $53.5 billion annually in developing regions. This works out at approximately US$8.54 per person (here), or NZ$12.21 per person.[i]

So, for the NZ$1.2 million the New Zealand taxpayer spent each year on 250 cows in Myanmar, we could have provided approximately 98,000 women and their children with basic contraception, and maternal and newborn health interventions. For the money spent each year on each cow (NZ$4,800) we could have helped 393 women.

I’m not necessarily arguing that New Zealand should have invested in maternal and child health interventions. The point here is that aid decision-making is complex. To get the most effective and efficient spend for taxpayers’ dollars, aid expenditure needs to be carefully assessed. There are many opportunity costs. In Myanmar, a country of 51 million people, New Zealand chose to invest in 25 farmers and 250 cows, with the potential of new employment opportunities for others in the long-term. For the same amount, New Zealand could have helped 98,000 women a year, for five years, to survive, gain an education, and contribute productively to the economy.

What this exploration highlights is how considering New Zealand’s close commercial priorities first in aid decision-making led to opportunity costs in known development gains elsewhere. In working to achieve development outcomes, win-win investments generally do not withstand careful country contextual analysis. Any benefit to a donor should be considered a possible side-effect, not a reason to invest. Deciding where to spend aid based on donors’ close interests wastes money, and with-holds opportunities from the very people aid is supposed to support.

Jo

I believe business is the key.. influence peoples lives through business cause it breaks down all barriers..

Yes funding 250 cows and expecting a meaningful outcome is fanciful.. best help those poor women..

The other way is allowing them to work in NZ in industry and educate them this way..

Hi Peter,

Thanks for your comment. I agree business is crucial. But it is not the only sector or activity that is crucial to any particular country’s development. There is no one road or one answer to sustainable development. This means to me that decisions about how to spend aid and on what require careful country context analysis, and the active involvement of various stakeholders in the country concerned.

Re: women working in business, there are many precursors that need to be in place before that can occur, all of which require their voices in analysing their situation. In my experience, one precursor is often supporting women to have the number of children they want, so they are actually able to leave the house and their caring responsibilities to go to work.

Social progress is complex. Why make it even harder to achieve benefits from NZ ODA for the poorest people by trying to also use ODA to advertise and sell NZ businesses? I thought that was what NZTE was for.