There is no one good way to give foreign aid. Simply giving individuals money is all the rage at present. It often works well but doesn’t build hospitals or roads. Donors can construct infrastructure themselves of course, but if the host country is poorly governed, today’s glistening infrastructure projects often turn into tomorrow’s white elephants. In theory, donors can solve this problem by using aid to improve governance. It’s excellent – in theory – but in practice it’s very difficult. Another alternative is to ignore the state and fund NGOs. Much like giving people money, this can work. But, once again, there are some things NGOs simply cannot do.

There is no one good way to give foreign aid. Simply giving individuals money is all the rage at present. It often works well but doesn’t build hospitals or roads. Donors can construct infrastructure themselves of course, but if the host country is poorly governed, today’s glistening infrastructure projects often turn into tomorrow’s white elephants. In theory, donors can solve this problem by using aid to improve governance. It’s excellent – in theory – but in practice it’s very difficult. Another alternative is to ignore the state and fund NGOs. Much like giving people money, this can work. But, once again, there are some things NGOs simply cannot do.

Aid can help. But if donors want it to, they need to choose carefully – matching different approaches to the contexts they find themselves working in.

Of the approaches donors can use, budget support has had a particularly turbulent history: the source of both idealistic aspirations and furious controversies. As a form of aid, it seems straightforward, involving aid agencies simply giving money to the governments of poorer countries to spend as they more or less please. (I’ll return to the “more or less” bit in a second.)

It’s simplicity is its charm: if all their aid were given as budget support, donors would no longer have to worry about managing thousands of projects. Recipients wouldn’t have thousands of other countries’ projects dotted around their social and economic landscapes either. But they would have money to spend on promoting development in ways that were responsive to the needs of their people. Perhaps even, free from the meddling of outsiders, and with enough money to actually do things, developing countries might start governing themselves better.

It’s charming, but nothing in the world of aid is ever that easy. Most aid-recipient countries have governance problems. Hopefully, they won’t one day but for now that’s the reality. Under these circumstances, it would be unwise for donors to simply write blank cheques. (“Oh, sure, you want to buy tanks, no worries, fire away.”) And so budget support has historically come with conditions (or “conditionalities” as they are called in the world of aid). At times these have been ineffectual, ignored by recipients. At other times, driven by contentious orthodoxies, they have been extremely controversial.

Budget support isn’t that simple after all. But there is still a case for using it, carefully, as part of a suite of approaches to giving aid. In their book Retooling Development Aid in the 21st Century: The Importance of Budget Support, Shahrokh Fardoust, Stefan G. Koeberle, Moritz Piatti-Fünfkirchen, Lodewijk Smets and Mark Sundberg make that case.

The book is not an impassioned piece of advocacy. It is thorough and scholarly. (The authors all have academic and/or World Bank backgrounds.) The book covers the history of budget support, situates it amongst the myriad of other similar, and not so similar, means of financing development, discusses different types of budget support in detail, distinguishes budget support given in times of crisis from longer-term approaches, and outlines the options for giving it. As it does all this, the book provides many useful examples.

Beyond the specific examples, the authors also bring systematic econometric evidence to bear on the question of what determines the performance of World Bank budget support programs. (Short answer, careful preparation within the World Bank, and perhaps policy quality at the recipient end; however a lot is unknown about the recipient end.) The authors also look into the ability of budget support to bring successful policy reforms in its wake: here the findings are very mixed (my view) or suggestive of success (the authors’ take).

Although my interpretation of the econometric evidence presented in the book is less positive than the authors’, I was still persuaded that budget support can work when it is well matched to context. There’s clearly a case for it. And the book is at its best when it builds on this case and discusses the practicalities of delivering budget support. In places, the book was too in-depth and a tough edit would have improved its readability. But the detail will be very valuable for readers with specialist interest in the topic.

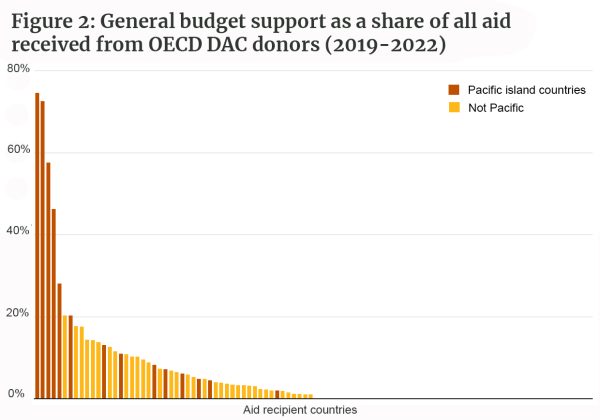

Hopefully, some of those readers will be in the Australian and New Zealand aid communities. According to OECD DAC data, both countries make more use of budget support than most donors (see Figure 1). What’s more, many Pacific countries receive comparatively large shares of their aid in the form of budget support (see Figure 2). Like it or not, budget support is big in this part of the world.

Notes: The data are not perfect or fully complete, but they are fit for comparisons. Please note that the Pacific countries that receive very high shares of total aid as budget support are typically countries with constitutional relationships with the USA or New Zealand. Percentages are averages from 2019 to 2022. COVID-19 has had an influence, but not that much. Download the workings here.

Source: OECD DAC CRS Database.

Budget support is not the only way aid can be given, but it is an important tool in the kit, and it can be made to work well. Anyone who wants to help make budget support work, or even just understand it, should take the time to read this book.

Disclosure

This work was undertaken with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The views are those of the author only.

Very interesting and important issue Terence, thanks.

I have recently been involved in a review of Australian budget support in the Pacific and your overall comments, and book’s findings, ring true. Our review found several positive aspects to Australian budget support. First, Australian funding was genuinely additional to, and did not substitute or displace, the partner government’s own domestic expenditure effort (“fungibility”). That is an important first step to making a positive impact. Second, Australian budget support was particularly valued because it was (i) 100% grant (not adding to debt) but also because (ii) it was “predictable” – sometimes moreso than from their own government – so local managers could plan programs with some degree of confidence. Third, because much of the partner government’s own expenditure effort in the health sector was absorbed by salaries, the “additionality” of Australian budget support then funded important and high impact outreach programs delivering primary health care to more remote rural areas that would not have occurred in the absence of that funding.

But our review also identified some challenges. For example, it is not always clear or obvious how even relatively large amounts of budget support achieve “results” or impact on the ground. That is particularly because the health system strengthening aspects that are potentially available with budget support occur “under the bonnet” in the Ministry of Health and are not necessarily as visible or obvious as a more traditional, stand alone, donor driven infrastructure project. Another challenge is that for budget support to be the catalyst for policy dialogue, and to get traction in terms of health system reform, there needs to be a robust monitoring and evaluation system that could / should then used to generate insights, lessons, and ongoing program improvements and feedback loops. Such active monitoring, evaluation and learning is different to, but builds on, more routine “reporting” of expenditure and disbursements.

The book you have reviewed would seem to have good lessons to help strengthen the impact of budget support. Another useful resource is a 2021 World Bank report titled “Following the Government Playbook?: Channeling Development Assistance for Health through Country Systems”. Thanks again for your blog.

Thank you Ian,

That’s an excellent comment. The findings of the evaluation sound very sensible and nuanced. They ought to be very useful to the aid program.

The evaluation also sounds like a very helpful resource for scholars and other aid practitioners. If the evaluation is available online could you please post a link to it?

Thanks again.

Terence

Definitely going to check out the book. Interesting read and while I largely agree on carefully assessing budget support as an aid tool to match context, I think that both New Zealand and Australia have tried in the Pacific to use budget support as a form of strengthening governance and engaging in policy dialogue & reform with Pacific island countries (take Samoa and Tonga’s respective joint policy reform dialogue for instance). In my view, its too dismissive to say that budget support is an alternative donors may use so that they dont have to manage a thousand projects. Australia provides both sector and general budget support to many Pacific island countries, using both aid tools as a means of leveraging partnerships for effective development … and of course advancing national interests.

Thanks for the much welcomed food for thought.

Thank you Aulola for a good comment.

I agree, New Zealand and Australia have tried budget support in the Pacific. It would be interesting to learn more about the circumstances associated with its success and failure.

I also agree that, in practice, no donor will ever abandon all their projects in favour of an entirely budget support focused approach. In reality, (good donors) will adopt a mix.

Thanks again

Terence

Hi Terence, really interesting – thank you! Just wondering – on what basis do you say that COVID-19 did not make that much of a difference to the scale of budget support as a % of total aid. If my calculations are correct, based on the attached Excel data comparing pre-COVID (2019) to post-COVID (2020-2022), it seems that budget support as a % of total donor aid has slightly more than doubled from about 1.95% to around 4% for OECD countries, for multilaterals the increase has been a bit larger, from 11.6% to 26%, while for Australia the change appears to have been very big, increasing almost fivefold from 1.19% to 5% – still small compared to the total aid program, but a big increase from where it started.

Hi Rohan,

Good point.

To clarify my point:

If you compare 2019 with 2022, Australia and New Zealand’s relative rankings have not changed much. (i.e., compared to most other donors, they drew on budget support more pre-Covid too.)

Similarly, relative to other recipients most PICs received comparatively large shares of budget support both before and during Covid.

It is true though that, as you say, absolute %s have increased in both cases. And this is a good point, in terms of absolutes both Australia and NZ use budget support more than they did once, so should be thinking about how to deliver it well more. The same is true for Pacific recipients.

As an aside, 2021 was a really big year for budget support in Australia and NZ. In an absolute sense it now seems to be on the wane.

Thanks again for your comment.

Terence