Donor agencies are increasingly interested in sharing the costs of private investments in developing countries to promote economic development goals. Costs might be shared in order to reduce risks for private investors to acceptable levels or compensate a private investor for the provision of public benefits. Competitive challenge funds are a popular format, channelling resources to the private sector to bring about investments and activities with positive development outcomes. It is generally expected that such donor support triggers private activities that would otherwise not happen, or that it makes them better (e.g. by enhancing their viability or pro-poor impacts), or helps make them happen significantly sooner; in other words, donor support should be additional.

Agencies can improve on current additionality assessments. Even though additionality is typically a formal requirement of donor support to business, agencies’ assessment criteria is often limited or vague; assessment processes are often confined to brief justifications from businesses; and there are typically no overarching internal guidelines within agencies on how additionality is considered. In sum, agencies are often unable to make a credible and convincing argument for the additionality of their support. Yet pressures are rising to demonstrate that partnerships with business make good use of public resources, not least as media attention focuses on donors’ funding decisions. For example, a recent newspaper article notes that many “critics questioned why some of Britain’s most successful and highly profitable firms are being given taxpayers’ cash for projects they could easily fund themselves.”

While it is impossible to ‘prove’ or ‘exactly measure’ additionality, agencies can enhance their additionality assessments in practical ways and do more to maximise the added value of public funds. With this in mind, member agencies of the Donor Committee for Enterprise Development (DCED) explored what good practice in demonstrating additionality could look like – based on the practical experiences of practitioners and funders of partnerships with business. The resulting report summarises eight key principles and criteria that can guide agencies in their process of selecting business projects for support. It encourages agencies to “do as much as possible” to use the criteria and principles outlined, but offers agencies the flexibility to adapt the exact scope and depth of their assessment to their specific context, resources and objectives.

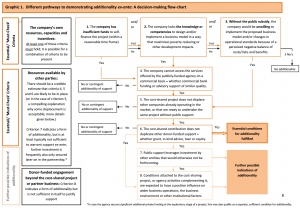

Eight criteria for assessing additionality. What does ‘assessing additionality’ mean in practice? As a first step, the agency must establish at least one of the following: the company cannot self-finance the project (within a reasonable time frame); it does not have the knowledge or skills to develop and implement the project alone; and/or it is unwilling to invest in the project because it perceives the costs or risks to be higher than the benefits. As a second step, the agency needs to obtain a good estimate of the resources available from others: if the company lacks the finance or knowledge for the project, the agency should establish, with reasonable credibility, that the company is most likely unable to access equivalent support on a commercial basis. Ideally, it should also make a convincing case that the cost-shared project is unlikely to displace investments by other companies operating or ready to enter the market. Finally, the agency should be able to show that its support does not duplicate other donor-funded support.

Eight criteria for assessing additionality. What does ‘assessing additionality’ mean in practice? As a first step, the agency must establish at least one of the following: the company cannot self-finance the project (within a reasonable time frame); it does not have the knowledge or skills to develop and implement the project alone; and/or it is unwilling to invest in the project because it perceives the costs or risks to be higher than the benefits. As a second step, the agency needs to obtain a good estimate of the resources available from others: if the company lacks the finance or knowledge for the project, the agency should establish, with reasonable credibility, that the company is most likely unable to access equivalent support on a commercial basis. Ideally, it should also make a convincing case that the cost-shared project is unlikely to displace investments by other companies operating or ready to enter the market. Finally, the agency should be able to show that its support does not duplicate other donor-funded support.

The case for additionality may be reinforced if the agency can also demonstrate that it will leverage funds from other public or private parties, or that it is likely to bring about improvements beyond the cost-shared project or partner business (such as in the standards applied to the company’s wider operations or in the broader business environment). Ways to assess the levels of innovation and risk of a project should also be clearly documented by the agency; the higher they are, the more likely it is that donor support is additional.

In the guidelines, you can find more detailed explanations of these criteria, proxy indicators for assessing them and practical examples.

Eight principles for assessing and enhancing additionality. While we won’t go into the detail of all the principles articulated in the guidelines, a few are worth highlighting. For example, it is critical that agencies are sensitive and creative in requesting information related to additionality from companies – to make it more likely that the answers they receive are honest and comprehensive. If possible, they should also maximise personal interaction with companies during the application or design process, especially to address doubts about additionality. Agencies should do as much as they can to triangulate (e.g. by speaking separately to different company staff and a range of other stakeholders) and to involve experts in the review and decision-making process. To do so, agencies can choose from, or combine, a range of different expert consultation methods (outlined in the report). Subsidy minimisation is a key principle in connection with additionality: identifying the minimum amount of support needed to trigger the desired actions should be an important consideration in the project selection process. Providing too large a subsidy might not reduce additionality but it does waste money.

Eight principles for assessing and enhancing additionality. While we won’t go into the detail of all the principles articulated in the guidelines, a few are worth highlighting. For example, it is critical that agencies are sensitive and creative in requesting information related to additionality from companies – to make it more likely that the answers they receive are honest and comprehensive. If possible, they should also maximise personal interaction with companies during the application or design process, especially to address doubts about additionality. Agencies should do as much as they can to triangulate (e.g. by speaking separately to different company staff and a range of other stakeholders) and to involve experts in the review and decision-making process. To do so, agencies can choose from, or combine, a range of different expert consultation methods (outlined in the report). Subsidy minimisation is a key principle in connection with additionality: identifying the minimum amount of support needed to trigger the desired actions should be an important consideration in the project selection process. Providing too large a subsidy might not reduce additionality but it does waste money.

To connect all the information relevant for assessing additionality, agencies should develop a clear, transparent narrative on the theory of change underlying the collaboration. This would capture an overall assessment of the counter factual, i.e. what would happen anyway, and a clear articulation of how the collaboration is expected to change the company’s activities. Such an approach is preferred to complicated indices or other quantitative measures of additionality. More generally, it is useful for agencies to internally document the additionality assessment criteria and processes used, as this can inform staff and enhance external communication and accountability.

Further suggestions for enhancing additionality assessments. After project completion, agencies can use qualitative business surveys to deepen or revise their initial understanding of the additionality of their support. A few agencies have done this internally, and independent assessments of this kind could also be considered. Similarly, and although this is more difficult, it could be valuable for more agencies to explore ex-post evaluations of a selection of rejected projects that are roughly comparable to others and that did get support.

More generally, it would be easier for agencies to work towards good practices in additionality assessments if these were considered upfront in the design of cost-sharing mechanisms. The guidelines provide a number of options in this regard.

You can download the full guidelines here. If you would like to share any feedback or make suggestions of further practical examples, please email Melina Heinrich.

Melina Heinrich is Senior Private Sector Development Specialist at The Donor Committee for Enterprise Development.

A significant point not highlighted here but which I have seen referenced elsewhere is the importance of investing in undertaking this type of assessment at all stages by the aid agency. There are two aspects to this. One is that the aid agency should be investing in this in order to maximise value for money and to be able to collect information to feed into future decisions about how and where allocations should or should not be made. Another aspect is that aid agencies must take care not to shift the burden of this type of assessment onto businesses. This is of particular importance in the Pacific island region, where businesses are small with limited capacity – in some cases the senior management team comprises one or two people. Agency staff need to have the requisite skills to be able to use reports that the business generates for internal purposes as the basis of assessment of additionality (and other things) rather than creating new and burdensome processes.