Local aid workers and organisations must not only be accountable to the communities they serve but also meet the compliance requirements of international funding agencies.

Compliance frameworks are of course important to ensure the accountability and effectiveness of internationally funded programs. However, local humanitarian actors often find these frameworks to be top-down, overly rigid, and unsuited to volatile and politically complex crises. This persists despite the commitments made in the Grand Bargain to localise aid systems and simplify requirements such as those related to reporting.

Our evidence from Myanmar demonstrates that, while perhaps established with good intentions, international agencies’ compliance frameworks and related requirements can have unintended negative consequences for local actors and communities.

Since the military junta’s coup in early 2021, civilian populations in Myanmar have faced an escalating humanitarian emergency. In a country of approximately 56 million people, more than three million have been forced to flee their homes. This crisis is a direct result of the Myanmar military’s targeting of civilian populations and aid workers. In this context, local aid workers and systems are essential to ensuring vital aid for civilian populations, serving as a “lifeline for the population,” as one aid worker said.

Yet our interviews with leading members of Myanmar’s local humanitarian networks revealed a pattern of negative repercussions from the compliance requirements imposed on internationally funded aid programs, including increased security risks and the obstruction of vital aid flows.

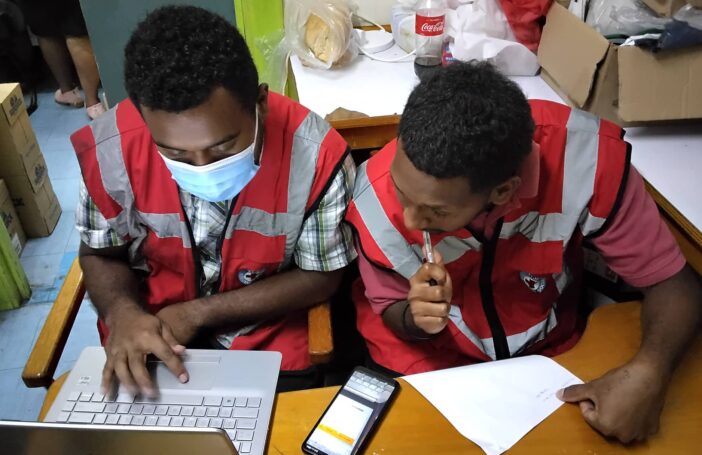

In Myanmar, the junta’s widespread use of extreme violence has led local organisations to develop very low-profile approaches which enable them to navigate military restrictions and reach communities in need of humanitarian aid. However, the compliance frameworks of international aid agencies commonly require local organisations to collect detailed information from “beneficiaries”, including sensitive information, revealing a dangerous lack of situational awareness. These systems can lead to critical delays in the delivery of humanitarian aid, undermining rapid and adaptive approaches.

International compliance requirements can also increase the already grave risks faced by actors on the ground. For example, the common requirement to obtain multiple quotes before procuring aid supplies can draw increased attention to aid workers and suppliers. A local Civil Society Organisation (CSO) member pointedly said:

[The Myanmar military] asked the local sellers to report to them when there is buying of temporary shelters … as they do not want [them] to reach [internally displaced people] and defence forces … But if we ask for three quotations using organisational formats in our small town, they will know us right away, putting us at risk.

Other requirements like the need to supply copies of drivers’ licences to show how supplies are transported, or the location of displacement camps, similarly jeopardise the low-profile approaches that local aid workers have developed.

During our interviews, aid workers described having to hide sensitive documents, often storing them at staff houses or concealing them on their bodies to cross through checkpoints.

There were exceptions, with some international agencies having increased the flexibility of their systems since the coup — for example, allowing for soft copies of documentation or reducing the need for multiple quotes for procurement. But these changes often took the form of short-term “emergency exceptions”, leaving local actors concerned about a return to “business as usual”.

For local humanitarian actors, there is a perception that this business-as-usual approach is linked to self-interest. As one local organisation leader said:

The most important thing that many INGOs and UN agencies should consider right now is the community, what they need and how they can support … Instead, they are just considering themselves, their survival, staff salaries, organisational survival, and self-preservation.

Amid Myanmar’s complex emergency, leaders of local organisations were not advocating for the abandonment of compliance systems; they acknowledged the crucial role they play. Instead, they argued for “a balance between what local partners can do in this context and how to ensure … minimum accountability requirements,” as said by one CSO member. They felt that this balance was currently lacking.

Not only can inappropriate compliance systems cause harm for local aid workers and organisations, they can also perpetuate unequal aid partnerships and create the perception of a lack of trust by international actors in their local “partners”. The knowledge and expertise of local aid organisations are often sidelined when compliance systems impose externally determined ways of working that are ill-suited to Myanmar’s volatile situation. This speaks to a disconnect between international approaches and the commitments made in frameworks like the Grand Bargain and the Charter for Change.

Many local organisations have developed contextually appropriate internal policies and systems to ensure accountability and compliance. However, international agencies too often deem these policies and approaches inadequate. This can force local agencies into prioritising what one CSO leader called the “capacity to comply” with internationally determined standards and criteria, rather than focusing on the “capacity to grow” their organisation and human resources based on local context and needs.

As highlighted by analysts like Hugo Slim, genuine localisation should enhance the agency of local populations in crisis situations to develop and lead their own humanitarian systems and approaches. Yet a “compliance-first” culture impedes the agency of local actors, reinforcing power inequalities in aid relationships.

It is vital that international agencies adopt a “do no harm” approach in relation to all compliance systems, ensuring that local partner and beneficiary security is always prioritised above other concerns, including financial risk management. They should also work with local organisations to develop systems that achieve a fair balance between their requirements and what is realistic in a context like Myanmar.

In developing and implementing compliance systems, they should “walk the walk” and not just “talk the talk” of shifting power to the local actors who are leading humanitarian responses on the ground.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Tamas Wells to this blog.