When we look back at the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the efforts of local responders are likely to dominate our collective memory. As national borders closed across the world, local actors, including government and non-government employees and millions of volunteers, stepped up to meet the urgent needs of those affected by COVID-19 in their own countries. From maintaining essential health services and promoting COVID-19 prevention and control measures, to providing food and psychosocial support to compatriots in lockdown, the response to the pandemic was primarily locally led.

For advocates of localisation, the central role of local and national responders during the pandemic presented a unique opportunity to shake up the humanitarian system. Would the renewed focus on national and local NGOs urge donors and humanitarian agencies to further their commitments on localisation articulated in the Grand Bargain? Would evidence of strong local leadership hasten reforms to the humanitarian system around trust, legitimacy and unequal partnerships between local and international actors? COVID-19 response guidance and strategy produced by humanitarian agencies in 2020 acknowledged that the changing loci of humanitarian operations and new delivery modalities could serve as a blueprint for longer term change.

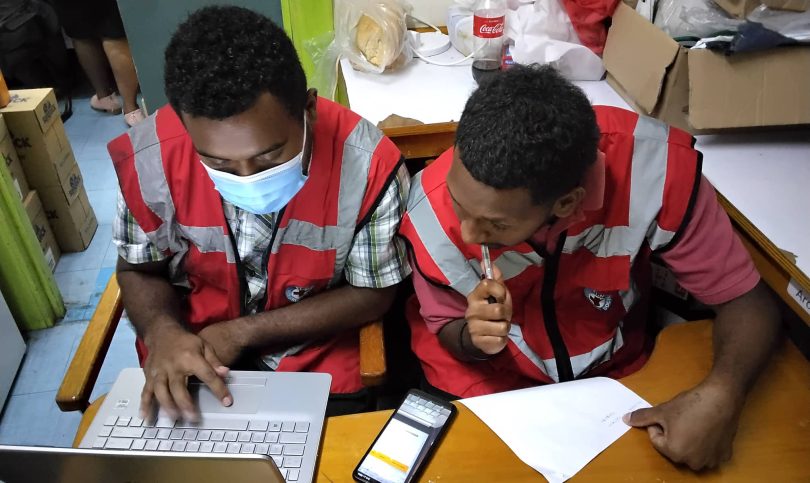

Two years into the global COVID-19 response, the Australian Red Cross approached six national societies in the Asia-Pacific region to better understand how their organisational sustainability was impacted by the pandemic. The findings, drawn from interviews with staff from the Red Cross societies of the Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Indonesia, Mongolia, Myanmar and Vanuatu, and IFRC head or regional offices, are presented in a new Australian Red Cross report.

The research showed that the pandemic certainly shook things up. It was (and is) true that all six Red Cross national societies played a leading role in their countries’ preparation and response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, despite strong local leadership and large inflows of COVID-related funding, key barriers to greater localisation remain undisturbed. Two years on, the struggle to cover basic operating costs, familiar to all NGOs, has persisted, and the challenge of scaling up to respond to the increasing demands of the humanitarian landscape is even further out of reach.

The researchers asked national societies about the effects of the pandemic itself. Unsurprisingly, they reported the pandemic had a significant impact across nearly all aspects of their operations. All national societies reported struggling to retain staff and volunteers due to a combination of health concerns, low pay and job insecurity. Mongolia Red Cross Society reported one-third to one-half of staff and volunteers contracted COVID-19, with remaining staff and volunteers working up to 15 hours a day, seven days a week, to respond to the double emergency of extreme cold weather and the pandemic.

National societies also described the challenges of adapting to changing government restrictions and transitioning to remote operations. This extended to fundraising efforts, which were significantly constrained and, combined with contracting economies, resulted in a sharp decline in locally generated revenue.

Even with these significant limitations on national society operations and extremely high demand on their services, most international donors, including multilaterals, remained rigid in their approach to restrictively earmarked, project-based funding. While such funding allowed national societies to fund activities for specific pandemic-related purposes, for example COVID-19 preparedness and support to vaccination campaigns, it did not offer the flexibility they needed to rapidly respond to their changing operating environments, nor cover day-to-day operating expenses. A group of Pacific national society staff explained:

We know what needs to be done but we can’t get the money to do it. We give them a master plan, but they still do things their own way. They like to tie funds to specific activities, they don’t want to give us money to spend on what we know we need … We don’t have enough autonomy.

A critical aspect of every organisation’s sustainability is its ability to cover core costs, such as essential overheads and staff. The perfect storm of limited local fundraising opportunities and increased demand on national society services meant that covering core costs became a major struggle for all national societies during the pandemic. This could have been mitigated by more flexible funding from international donors. Instead, heavily earmarked funding (with business-as-usual budget caps on overhead costs) and burdensome reporting requirements exacerbated the situation – which resulted in reduced opportunities for organisational growth, and sometimes led national societies to make risky cost-saving decisions.

Informants expressed particular frustration at this inflexibility, and being unable to leverage international support to cover core costs or repurpose resources to meet higher priorities. Most informants put donors’ rigid funding approach down to a lack of trust in local organisations’ ability to meet their high standards. As an Indonesian Red Cross colleague told us:

It is much better for donors to invest more trust in local teams on the ground instead of trying to manage everything. Locals know what is needed and they can manage more efficiently. Accountability must be considered, of course, but more delegation on the ground is essential. What is needed is more delegation and more trust.

Far from the blueprint envisaged by localisation advocates, the pandemic has revealed the extent to which unequal relationships relating to funding, trust and accountability can hinder change. With local organisations at the frontline of the pandemic response still unable to cover their basic operating costs, and looking ahead to yet more boom-and-bust cycles of international funding, the core localisation commitments of Grand Bargain 2.0 are as urgent as ever. Without breakthrough approaches to untied, multi-year funding partnerships that take trust in local organisations to heart, systemic inequalities will keep on limiting us from being truly effective – no matter how devastating the next shock is.

Read the Australian Red Cross report The long tail of COVID-19: impacts on the sustainability and resource mobilisation of national Red Cross and Red Crescent societies in the Asia Pacific region.

Disclosure

The report from which this blog draws, and the work of the Australian Red Cross in supporting local actors (Red Cross and Red Crescent national societies) in their role as humanitarian leaders, are financially supported by Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views are those of the author only.

Leave a Comment