Late in 2015, my team and I were asked to delve into the world of Virtual Reality (VR) to produce a series of 360-degree films for the World Bank focused on the issue of conflict across East Asia and Pacific. More than six months of production later, The Price of Conflict, The Prospect of Peace series is now online, with stories from Solomon Islands, Bougainville (Papua New Guinea) and Mindanao (Philippines).

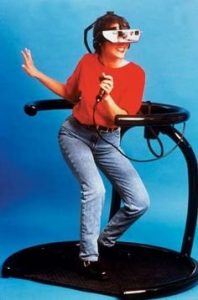

Yet jumping back to when I was initially asked to work on this, my initial reaction to this project was to try and talk people out of it. I had vague memories from the early 1990s of plastic helmets where people would awkwardly walk around a pixelated floating room, doing not much else besides provide amusement/bemusement for those watching from the outside.

Yet jumping back to when I was initially asked to work on this, my initial reaction to this project was to try and talk people out of it. I had vague memories from the early 1990s of plastic helmets where people would awkwardly walk around a pixelated floating room, doing not much else besides provide amusement/bemusement for those watching from the outside.

It wasn’t just these memories – nor the countless VR rollercoaster apps now flooding the App Stores – that clouded my opinion. Because clearly technology has made massive progress in the 20 years since, and many tout VR as the new frontier for how we will be entertained and informed. I’m first and foremost a believer that to tell a story truly well, the medium or technology should never be the most important thing; story should always come first. If the viewer/reader/consumer is thinking about the novelty of the cool tech they’re experiencing, then isn’t it actually just distracting them from the most important element; the story?

Seeing The Displaced in a Samsung Gear VR headset flipped my opinion. It opened my mind to the potential of VR storytelling. Yes, my initial minute watching this film was spent aware of the technology and the experience of having a 360-degree story told in front, behind and above me. But that awareness largely disappeared soon enough. I was quickly – to use the most frequently-used adjective associated with VR – immersed. I wasn’t just engaged because the events in the film were happening in a 360-degree format. I was more engaged, because within minutes I’d forgotten about the medium: I was integrated into it. I was ‘in’ the scene, floating up through those marshes in South Sudan.

The Displaced, and similar films such as Clouds Over Sidra, Waves of Grace, The Source or Collisions shows the potential for storytelling in this new medium, particularly for documentary and real-life storytelling. They’ve demonstrated that the VR medium can deepen the understanding of the viewer by putting them in the scene; bringing them closer to the reality than the traditional storytelling mediums we’re accustomed to.

More specifically, it’s the area that I work in – aid, development and humanitarian response – that gets me most excited about the potential of VR. Aid organisations are generally fairly skilled at bridging the gap between the work on the ground – the communities, conflicts or disasters they work in – and your average person living in a developed country. Yet it’s an incredibly crowded market. Each day thousands of organisations are competing for their share of air time on countless issues and causes. Consumers are justified in feeling tired or cynical.

VR and immersive 360-degree storytelling provides a way to cut out the noise and put consumers closer to reality on the ground in some of the world’s toughest and most extraordinary places than they’re ever likely to have the opportunity to do. We can never truly understand what life is like for a Syrian, Ukrainian or South Sudanese refugee child, but The Displaced helped people to connect with that experience in a profound way.

But it’s now the next step – beyond connecting people and creating empathy – that’s the key challenge: how do we ensure the immersive experience of VR inspires genuine action? Initial results across the sector are encouraging. UNICEF has reported that when Clouds Over Sidra has been screened as part of its face-to-face fundraising efforts, it’s seen a conversion rate from donors go from one in 10-13, to one in five or six. charity:water, with its VR film The Source, likewise has reported similarly impressive returns.

Our The Price of Conflict series is primarily targeted at senior government and institutional decision-makers, and the precedents in this space are similarly exciting. In a recent video on the UN’s push into VR, the UN’s Gabo Arora, the founder of UNVR Lab, says the impact of Clouds Over Sidra on the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2015 and the recent International Pledging Conference on Syria was significant; the latter seeing twice the funding to what was projected:

“When the film debuted in Davos, it was a sensation to everyone we showed it to. They come out of it very deeply moved. I’d say half the people who watch Clouds Over Sidra cry. …The film was then integrated with the Secretary General in the Kuwait pledging conference for Syria. He made everyone at the reception of the pledging conference watch it. And it really made a big difference in getting people to pledge more, to care more, and to be more involved.”

While time will tell on the impact of our films, the initial response to screenings of The Price of Conflict have been encouraging, with viewers repeatedly telling us the experience has changed their perception of conflict and recovery from it:

“I felt like I was right there… [with] the participants, learning about what the problems they’re experiencing were, and how our interventions could support real change in their lives,”

said one delegate.

“It’s as close to being on a field trip as I’ve ever been. It’s bringing you there,”

said another.

This last comment from one of our viewers is important to consider, given the potential outlay for producing VR content is likely a challenge for development communicators to get over the line, as recognised by UNICEF’s David Cravinho. Yet when compared to the cost of potentially taking donors on field visits, the value stacks up quickly, even before security and other logistical challenges are taken into consideration.

The final challenge ahead, however, seems to be the biggest hurdle: actually getting people to take the time to watch VR films in their genuine 360-degree VR form; to get them into the space, cut out the noise and normal distractions and commit to the film in its true experience. Samsung deserves credit for pushing their Gear VR headsets so strongly to help spread 360-degree content, and Google Cardboard (and now, Google Daydream) offer a relatively cheap solution for anyone with a new-ish smartphone.

With the VR 360 medium continuing to push further into the mainstream, the challenge for us, as content makers, is to make must-see content that audiences will want to take the time to completely cut themselves off from the outside world to watch. Because once they do, then VR’s impact has the potential to be life-changing.

Tom Perry is Team Leader – Pacific Communications for The World Bank. This post was first published on Medium.

The first three ‘The Price of Conflict, The Prospect of Peace’ VR films are now online, and best viewed through the YouTube app on iPhone or Android:

For more stories from behind the films, visit the website here.