Australian aid NGOs have a male leadership problem. The problem isn’t that there are men running NGOs–there’s nothing wrong with this. The problem is that a disproportionately high number of Australian NGOs have men at the helm. And, worse, my analysis suggests this isn’t because of a shortage of capable women.

The two most recent ACFID annual reports provide the gender make-up of ACFID member NGOs’ staff, boards and CEOs or directors for the 2013/14 and 2014/15 financial years. Not all Australian aid NGOs are ACFID members, but most of the major ones are, and there’s no reason to think ACFID members are any less women friendly than non-members. The data in the annual reports come from ACFID’s member surveys. Both years had response rates of about 85%. There’s no reason to believe there was any gender bias in survey responses.

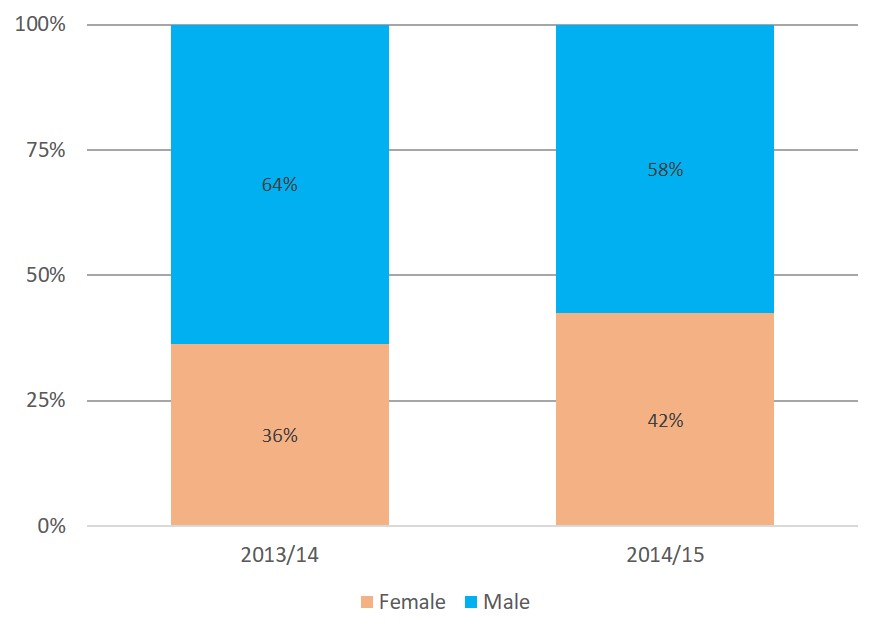

In the years of the surveys, a clear majority of NGO staff were women: 69% in 2014 and 66% in 2015. It seems reasonable to expect that this gender balance would be reflected in NGO leaders too. As the chart below shows, it isn’t. In both years about 60 per cent of NGO leaders were men.

Gender of CEO/director of Australian aid NGOs, 2013/14 and 2014/15

Why? One explanation could be that NGOs once employed more men than women. And, because it takes time to rise to the top, the current excess of male leaders is just a reflection of this by-gone age of man. Or it could be that women are hampered in their quest to become NGO leaders because they’re more likely to take time out of their careers to raise kids. If either of these explanations were true, women would be under-represented at the top simply because there haven’t been enough good female candidates.

Why? One explanation could be that NGOs once employed more men than women. And, because it takes time to rise to the top, the current excess of male leaders is just a reflection of this by-gone age of man. Or it could be that women are hampered in their quest to become NGO leaders because they’re more likely to take time out of their careers to raise kids. If either of these explanations were true, women would be under-represented at the top simply because there haven’t been enough good female candidates.

It’s possible these explanations may be partially true. But they’re not the main problem. Not, because a shortage of good women candidates is something that ought to affect all NGOs equally. And, if this was the case, the distribution of male and female NGO leaders would be more or less random–it wouldn’t be correlated with any other NGO traits. Yet there are correlations.

Fortunately, the correlations I found also highlight the type of NGO that needs to worry about this problem the most, and a good way of starting to resolve the issue.

When I ran logistic regressions I found that, controlling for other traits, religious NGOs were much less likely to be run by women. I also found that organisations with men heading their boards were much less likely to have female CEOs or directors. These findings were true when I looked at all NGOs and when I limited my analysis only to larger organisations. NGOs with more men on their boards were also less likely to have a female CEO or director, but this result was more fragile than the other two. (Regression specifications, the control variables I used, and the alternate specifications I used as robustness tests can be found in this spreadsheet.)

The chart below shows the average differences associated with religion and male board heads. On average, controlling for other variables, there’s a 47% chance a secular NGO will have a female CEO. There’s only a 24% chance a religious one will. There’s a 55% chance an NGO with a female board head will have a female CEO. There’s only a 34% chance an NGO with a male board head will.

Predicted probability of having a female CEO/director based on regression results

All I’ve shown is correlation, of course, not actual causation. In the case of religion, I’m pretty sure it’s not a belief in a god per se that is the issue. My guess is that the culprit is an unobserved trait that just happens to be more common amongst some religious NGOs — perhaps a particular world view. In the case of the gender of the chair of NGOs’ boards, a causal relationship is more likely given that board chairs are often the people who lead the recruitment of directors and CEOs. But it could still be some other unobserved trait, like world views, which causes both board chairs and CEOs or directors to be men.

Regardless of causality, my results point to a group of NGOs — religious ones — that need to pay the most attention to getting more women running their organisations. My results also suggest a good way all NGOs can start rectifying the imbalance in male leadership: get more women chairing their boards, and get more women on their boards. Even if issue isn’t simply men chairing boards being more inclined to appoint men as CEOs or directors, getting women into senior governance roles on boards is still likely to help with organisations’ world views and culture, and to make them more pro-women.

To be fair to Australian NGOs, they’re better than the private sector, and comparing the two years’ data suggests a possible trend of improvement. But my guess, given the concern for women’s empowerment which is–rightfully–so strong in the sector, this is a problem that people will want to tackle sooner rather than later. If that’s the case, my advice is to start with the board.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. Terence’s research interests include aid policy, the politics of aid, and governance in developing countries.

Thanks Ash and Garth,

I definitely like the idea of annually reviewing. I also think you explanations may be part of the story Ashlee, and they definitely warrant being looked into further. But they still don’t explain the religion and board gender correlations. These correlations suggest other issues afoot. Though I’m not 100% sure what they are.

There’s a great mixed-methods PhD in this for an aspiring researcher.

Terence

Yes, great post Terence. And I think Ashlee’s comments are also very relevant. Perhaps Devpol could do an annual review of the gender situation in NGO management to keep reminding people.

Great post Terence! I have a few other ideas of what could be part of the issue, obviously just anecdotal but I’d be interested what others think. One is that work-related travel – both domestic and international – is still often difficult for women with children, yet often needed to progress in this space and definitely needed in those leadership roles. Two could be burn-out – I have had several of my mid-career female friends leave the sector or go freelance/consultant because of the huge and unreasonable workloads expected of them in full-time positions in some NGOs – trying to balance that with family or other commitments sometimes becomes too much. It seems there is sometimes an idea that if you are willing to work in a not-for-profit, you are will to sacrifice pretty much everything for the cause, which is pretty problematic. Three, we should remember that DFAT still has issues getting women in leadership as well, and high-level public servants who have worked on aid would also be strong candidates for these NGO leadership roles. And four (like a recent study on the Aust public service highlighted), perhaps the more ‘sexy’ policy/advocacy/international program roles still tend to go to men, while women (anecdotally, obviously massively generalising) often seem to more predominantly work in areas such as communications, program admin, fundraising or as sector specialists in areas like health, education or gender — perhaps this kind of experience isn’t taken as seriously as that policy/advocacy experience when it comes to appointing NGO leaders? There also does seem to be a bit of a culture nowadays of bringing on outsiders – people from outside the development sector – for some of these leadership roles, so that could be another factor.