Our new report, Pacific Possible: labour mobility, provides a new way of quantifying the benefits of labour mobility. Normally, this is done by looking at remittances, but remittance data is very poor in most countries, including in the Pacific. And, more importantly, remittance data doesn’t capture the most important benefits that labour mobility provides – the benefits to the migrant. We need to think about benefits not to countries but to populations. A Pacific migrant doesn’t stop being part of the Pacific just because they migrate.

To capture this, we use new OECD data on the stock of Pacific migrants. This shows that there are some 420,000 Pacific migrants in OECD countries around the world, 4.4% of the Pacific resident population. To convert this into an income figure, we need to know how many of these migrants are working, and what income they are earning. Since detailed data are unavailable, we simply assume that migrants enjoy the average GDP per capita of the country that they have moved to. We also assume that they lose the net income (GDP per capita) of the country they leave behind. That is the opportunity cost of migration.

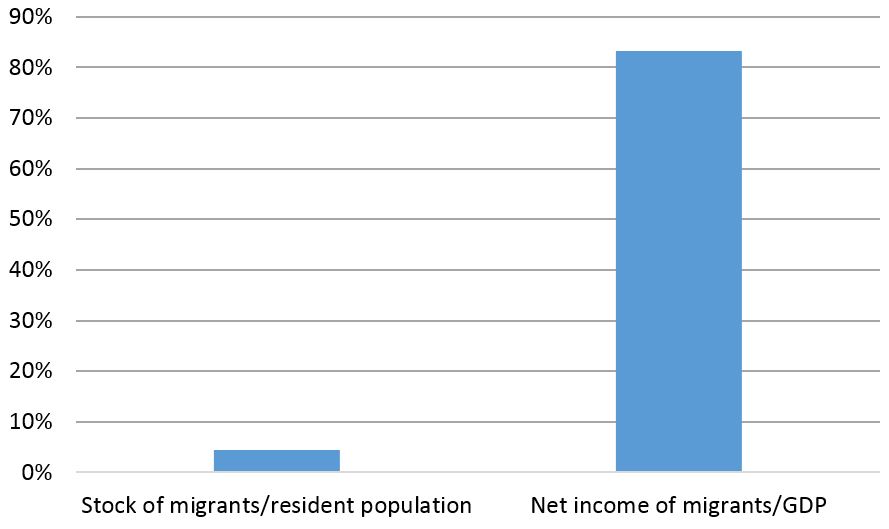

These assumptions are obviously very rough and ready, but they give us a good sense of the magnitudes involved. Using this method, the average net income of a Pacific migrant is $28,000, and the total net income of these migrants is $11.8 billion. That is 83% of Pacific GDP, which is $14.2 billion.

Figure 1: Pacific migrants relative to population and Pacific migrant income relative to Pacific GDP (2013)

Of course, that overseas income is not included in GDP, which is a figure that measures the value of domestic output. But how do 4% of the Pacific resident population enjoy an income equivalent to 83% of Pacific GDP? Because on average they earn so much more. Average GDP per capita in the Pacific is $1,500 (2005 prices). Average GDP per capita in the OECD is almost $30,000, or 20 times as high. 4 times 20 is 80. It’s the simple but powerful arithmetic that makes labour mobility such a game changer in the Pacific. Increasing the stock of migrants by one percentage point will generate an additional 20 percentage points of GDP. No other reform can bring comparable benefits.

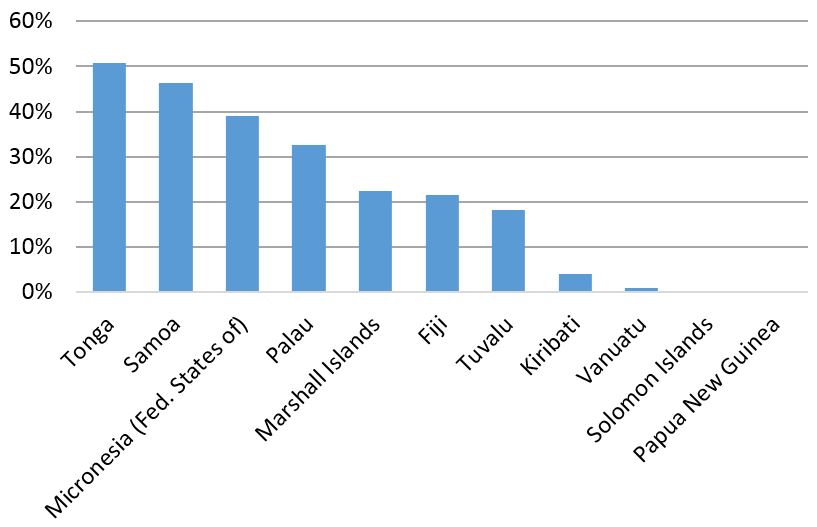

What is also clear from the data is the highly unequal distribution of the benefits of labour mobility within the Pacific. The figure below orders the Pacific countries covered by our report (those countries which are World Bank members) from highest to lowest in terms of population abroad. Tonga has the equivalent of half its domestic population abroad. PNG has just 0.2%, making it one of the most isolated countries in the world.

Figure 2: Pacific migrants relative to resident population (2013)

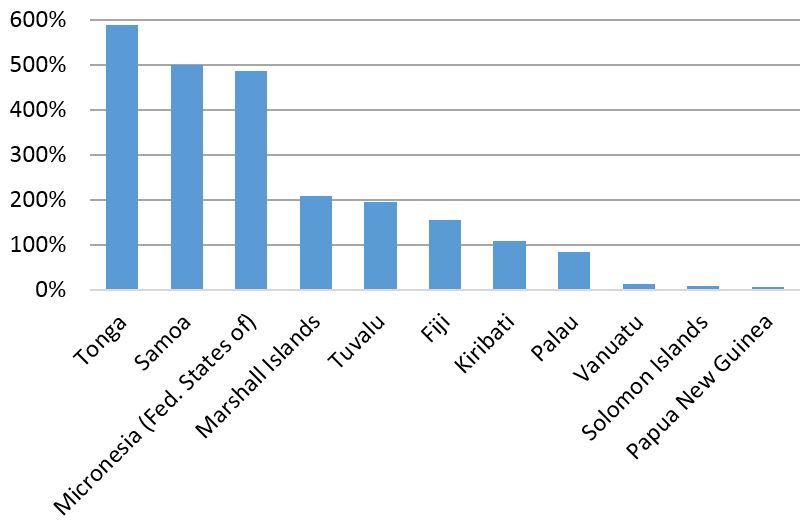

These differences are manifested in a huge range of ratios of net migrant income to GDP, which range from 600% (Tonga) to 6% (PNG).

Figure 3: Pacific migrant income relative to Pacific GDP (2013)

In our report we propose a number of reforms that could lead to modest increases in the number of Pacific migrants abroad, and significant increases in net overseas income. The aim is not just to increase total labour mobility earnings, but to spread opportunities to nations where labour mobility options are the most limited. The focus of our report on unskilled and low skilled labour mobility pathways ensures it is not only the highly educated that will be able to migrate.

You can read our report (and subsequent blogs) for the details of those reforms, and for a quantification of their impact. What we’ve tried to do in this post is demonstrate the importance of labour mobility for the Pacific. It’s not just about remittances. It’s about the income earning opportunities which give rise to those remittances. Much effort is exerted and much aid spent on boosting Pacific GDP. But poverty rates remain stubbornly high, especially in the low mobility countries of PNG, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, and in the atoll nations of Kiribati and Tuvalu. Let’s not forget the opportunities for Pacific islanders abroad, which even today are worth some 80% of Pacific domestic GDP.

Stephen Howes is the Director and Matthew Dornan the Deputy Director of the Development Policy Centre. Richard Curtain is an independent consultant and Visiting Fellow at the Development Policy Centre. Jesse Doyle is a Social Protection Economist with the World Bank and a Development Policy Centre Associate.

Read the full Pacific Possible: labour mobility report here, and a four-page summary here. You can also listen to podcast of the report launch at ANU here.

Leave a Comment