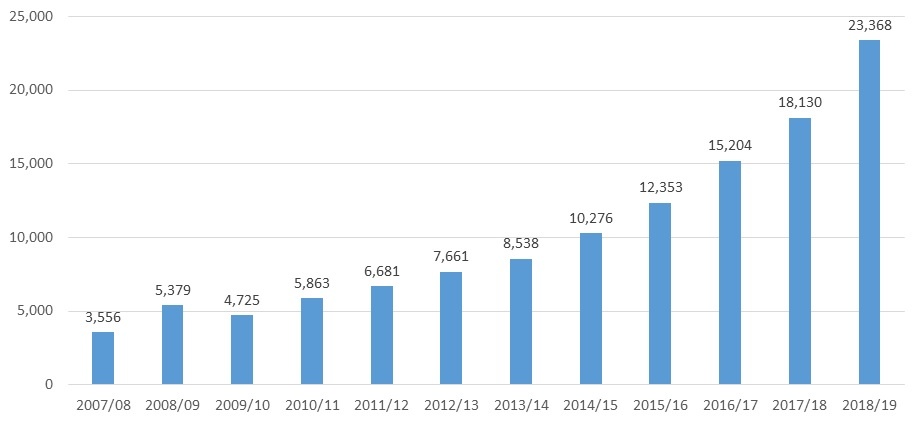

Seasonal labour mobility – temporary Pacific migrants working on Australian and New Zealand farms – is becoming big business in the Pacific. Or it was until COVID-19 came along and closed international borders. In fact, however, COVID-19 has increased the profile of the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP) in Australia and Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) scheme in New Zealand and we expect the number of workers in both countries to continue to grow once borders are reopened.

Research on the SWP and RSE has focused so far on the benefits of the schemes to both farmers and workers. In our new report, we shift the focus to the governance of labour mobility in general, and the SWP in particular. The report we are releasing today, Governance of the Seasonal Worker Programme in Australia and sending countries, is the culmination of years of research, including fieldwork undertaken over nine years in 11 countries. It analyses the management or governance of the SWP, and recommends ways to improve it, with the ultimate objective of promoting the sustainable growth of seasonal labour mobility from the Pacific to Australia.

While the report encompasses both Australia and sending countries, we focus in this blog on the latter. We encourage everyone to read the full report or, at least to download the executive summary which includes our recommendations.

Our starting point is that the SWP is not an aid program. There are no country quotas, and which countries get to send more workers is entirely up to the employers who use the scheme.

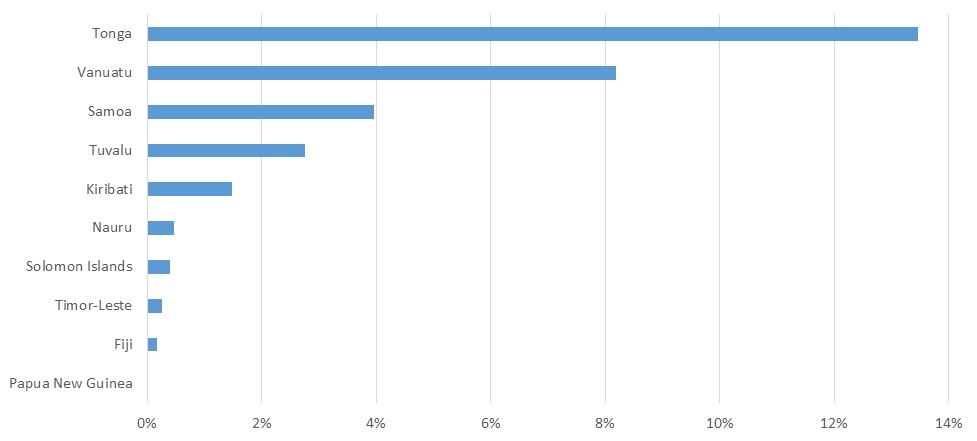

If countries were all equally attractive to employers, or if selection was random, then countries would participate in seasonal labour relative to their population. Papua New Guinea (PNG) would dominate, and tiny Tonga would send hardly anyone. Instead the picture is very different. Based on data from 2017-18, almost 14% of Tonga’s male population aged 20 to 45 years travels to work on Australian and New Zealand farms every year. Vanuatu is next with 8% and Samoa sends 4%. At the other end, Timor-Leste and Fiji send less than 0.5%, and PNG sends virtually no one at all.

Proportion of seasonal workers by male population aged 20-45, by country

Why have some countries done so much better under the SWP than others? Part of it is luck: some countries had a first-mover advantage. But SWP market shares are not stable, and Vanuatu and Timor-Leste have expanded in recent years at the expense of Tonga, which dominated the SWP in the early years.

A striking feature of SWP governance arrangements is how they differ across countries. Neither of the two biggest senders, Vanuatu and Tonga, rely on a “work-ready pool” – a government-run, pre-selected group of workers, which employers are required to recruit from. But Timor-Leste, the third biggest sender, and several other countries do. Vanuatu and Tonga are different in other ways. Vanuatu has a system of licensed agents; Tonga relies much more on direct recruitment by employers, who use informal intermediaries.

Our report tries to make sense of the great range of arrangements in place across sending countries via a categorisation of countries into “government-central”, “government-light” and an intermediate “in between” category.

Vanuatu and Tonga typify the government-light approach. Both countries have relied heavily on the private sector not only for the selection of workers, but also to assist with various regulatory functions, such as pre-departure briefings. On the other hand, we label as government-central those sending countries that rely exclusively on a work-ready pool, and whose governments take on the regulatory duties themselves. This category includes the smaller senders of Kiribati, Nauru, PNG, and Tuvalu, as well as, of late, Timor-Leste. The intermediate category – in which a work-ready pool is a significant, but not compulsory part of the recruitment process (or in which employers can at least add workers to the work-ready pool) – includes Samoa, Fiji, and Solomon Islands (and until recently Timor-Leste).

Our report rejects the argument that there is a “best” model of governance. Rather there are limitations of each approach that need to be taken into account. The problem with the government-central approach is that employers have made it clear through surveys that they dislike being forced to use work-ready pools. The returning worker is crucial to the success of the SWP. Employers want to be able to ask returning workers and other trusted intermediaries to select new workers when they need them. Timor-Leste has done well in the past by allowing for that flexibility. Its recent decision not to allow employers to nominate workers into the work-ready pool threatens its success.

The other problem with the government-central approach is that it gives the government an easily abused monopoly over the selection process. It can also run into capacity constraints. If governments are unable to manage the recruitment process to meet the deadlines of employers, employers will look elsewhere.

At the same time, the government-light approach is not a panacea either. Having licensed agents has worked well – though has been far from unproblematic – for Vanuatu, but it is a model that was tried and abandoned by the Solomon Islands. What is clear though is that, if a country does succeed and grows its numbers, it then needs to put more resources into SWP governance, including to troubleshoot the problems that invariably arise once workers are dispersed over farms across Australia. As government-light countries provide better resourcing to their labour mobility arrangements, they will inevitably move away from the end of the spectrum towards a more intermediate position.

Vanuatu and Timor-Leste have both recently announced that they will move, in different ways, in the direction of a government-central model. This highlights how unsettled labour mobility governance arrangements still are in the Pacific. While we are aware that some of what we describe in our report may soon become out of date, we hope that the documentation and analysis we provide will be useful, and we are confident in our conclusion that neither extreme of government-central and government-light is sustainable.

You can download the full report “Governance of the Seasonal Worker Programme in Australia and sending countries” and executive summary here. View the webinar here.

Leave a Comment