In 2008 a change of government brought major changes to the New Zealand government aid programme. It’s now more than eight years since this transformation began, and what was once new is now normal for New Zealand aid.

In 2015 the Development Policy Centre conducted the first ever systematic survey of New Zealand aid stakeholders (contractors, NGOs and other stakeholders that work regularly with the New Zealand government aid programme). We ran the survey to gauge the current state of New Zealand aid by gathering the views of people who have first-hand experience of its performance. We have just published the report [pdf] based on the data that emerged from the stakeholder survey. The report sheds light on New Zealand aid’s ‘new normal’.

In short, the results are mixed, highlighting both strengths as well as room for improvement.

The survey itself was run in two phases. The first targeted senior managers from New Zealand aid NGOs and contracting companies that undertake aid work funded by the aid programme. The second phase involved self-selection and was conducted to obtain the views of a broader group of New Zealand aid stakeholders. Participants in the second phase included less-senior NGO and contracting company staff, the staff of multilateral organisations, academics and a small number of employees of developing country governments. 62 people participated in the first phase of the survey, and 74 participated in the second phase.

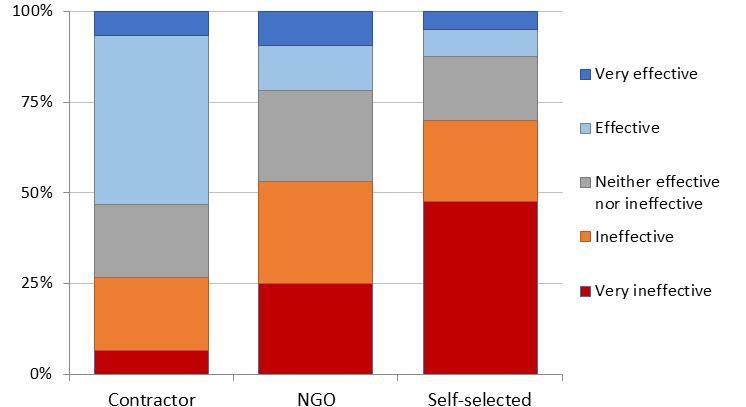

In most of the areas the survey covered, there was also a clear division between respondent groups. On average, contractors from the first phase of the survey provided the most positive responses to questions, while NGOs from the first phase were less positive, and the least positive responses came from participants in the second phase of the survey.

One clear example of this was the sharp divide in opinion about Foreign Minister, Murray McCully, the minister who has presided over the aid programme since 2008. On average, private sector contractors appraised the minister’s leadership of the aid programme positively, while NGOs tended to have a negative take on the minister and participants in the second phase of the survey were more negative still.

Stakeholders’ opinions were divided about the foreign minister

Figure notes: The categories contractor and NGO come from the first, targeted, phase of the survey.

The category self-selected is derived from responses to the second, open, phase of the survey.

The question asked was: “How effective do you think New Zealand’s current Minister of Foreign

Affairs is in managing New Zealand’s aid programme?”

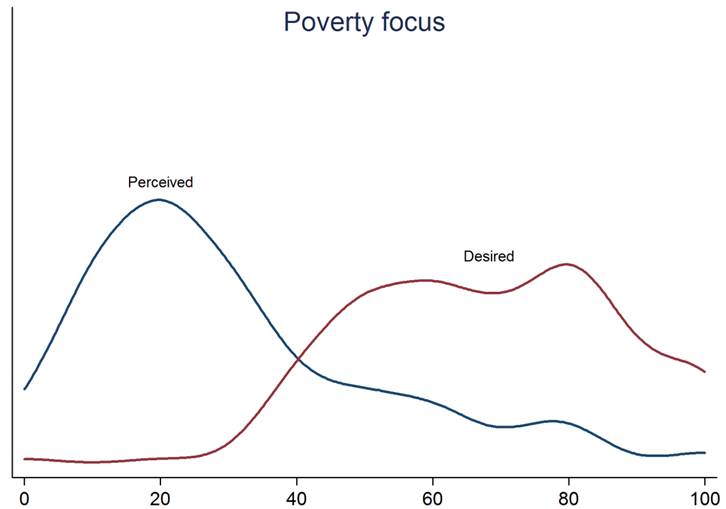

There were some areas where the different respondent groups were in agreement. In some instances, these highlighted areas of concern. For example, worryingly, most stakeholders – whether they were from NGOs, contracting companies, or participants in the second phase of the survey – thought that the main focus of New Zealand aid was not helping poor people in poor countries, but rather advancing New Zealand’s interests. The majority of respondents in all groups thought more focus should be placed on tackling poverty.

Most stakeholders want the aid programme to focus more on poverty than it currently does

Figure notes: This chart shows the distribution of responses to a question that asked stakeholders to allocate relative weights (out of 100) for various aid goals. This chart focuses on the extent to which stakeholders thought aid was focused on poverty (blue) and the extent to which they thought it should be (red). Peaks in the lines are where responses were most frequent.

On the other hand, there were areas where findings were quite positive, even taking into account the differing opinions of different groups. For example, when asked how effective they thought the aid programme was overall, the majority of contractor and NGO respondents from the first phase of the survey thought the aid programme was effective. And while respondents from the second phase of the survey were less upbeat in their assessments, positive responses were still more frequent than negative.

Most stakeholders thought the aid programme was effective

Figure notes: The question asked was, “How would you rate the effectiveness of the New Zealand aid programme?”

In addition to high-level questions, we asked about specific aid programme attributes. By and large those attributes that were rated most highly by stakeholders had to do with high-level aspects of the aid programme’s operation, such as its strategic clarity and results focus. The aid programme tended to score worse in procedural areas such as speed of decision making and avoidance of micromanagement. The aid programme scored poorly with respect to staff continuity, but quite highly for staff expertise.

As with high-level questions, contractors were more positive in their appraisal of most of the specific aid programme attributes we asked about. NGOs and Phase 2 stakeholders tended to have a somewhat less positive take.

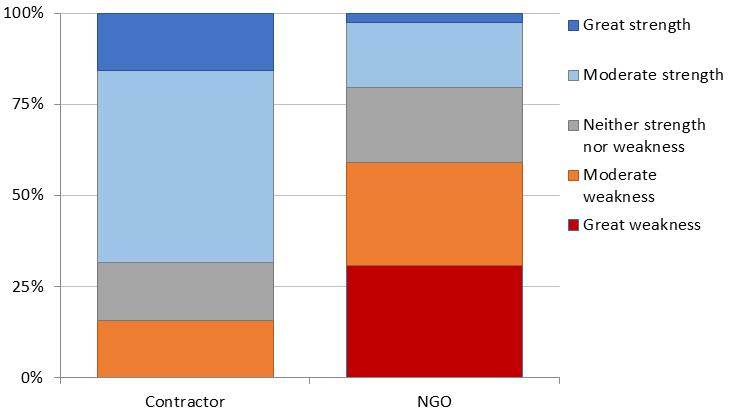

The more negative appraisals offered by NGOs are probably, at least in part, the product of the problems that have plagued the aid programme’s NGO funding mechanisms since they were overhauled in the wake of the 2008 election. Reflecting these problems, when they were asked about funding predictability, few NGO stakeholders thought it a strength, while most contractors did.

NGOs are more likely than contractors to see funding predictability as a weakness or great weakness

Figure notes: The question asked was effectively, “Please indicate the extent to which you believe the New Zealand aid programme as it currently stands possesses predictability of funding.”

When we restricted our analysis to the first, most robustly sampled, phase of the two countries’ surveys, for most of the attributes we asked about, the New Zealand government aid programme rates as more effective by New Zealand stakeholders than the Australian government aid programme was appraised by Australian aid stakeholders. (Even with Phase 1 and Phase 2 data combined New Zealand scored better on more attributes, although the difference was less.)

Although some of the difference between the two countries may simply be a product of the Australian aid community still coming to terms with the major changes that have occurred to Australian aid, part of New Zealand’s better performance is likely to be the result of the New Zealand government aid programme having been spared major budget cuts. Another probable reason, suggested by New Zealand’s better scores in areas such as strategic clarity and staff expertise, is that the New Zealand government aid programme has remained a coherent group within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, whereas the Australian government aid programme has been much more fully integrated into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Aspects of the 2015 New Zealand Aid Stakeholder Survey, such as the generally positive overall assessment of the effectiveness of the New Zealand aid programme, are quite encouraging. And New Zealand’s aid programme functions reasonably well in a number of important areas. At the same time there are also areas of concern, and there is scope for improvement. The challenge now for the New Zealand aid programme, and the New Zealand development community more broadly, is to take advantage of the opportunities that present themselves and make sure this improvement occurs.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow and Camilla Burkot is a Research Officer in the Development Policy Centre. The 2015 New Zealand aid stakeholder survey report is available here [pdf] and the underlying survey data are available here [zip]. You can also read more about the New Zealand and Australian aid stakeholder surveys on the Devpolicy website here.

Leave a Comment