The first entry of this series of blogs on New Zealand aid read from an ODI report [pdf]: “By 2025 global poverty will be concentrated in fragile, low-income states.” That could have been more precise, because the report also pointed out that by 2025 global poverty will be an overwhelmingly African problem. It noted that in 1990 about 15% of the world’s poorest lived in Africa. Today, over 50% of the poorest live in Africa and by 2025 this will have risen to over 80%. This post will take a closer look to see how New Zealand aid is facing away from this challenge and why this is a problem.

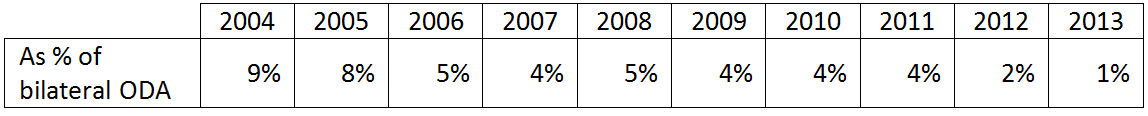

The first striking feature of New Zealand aid to Africa is that it has been going the way of Maui’s dolphin; plummeting from 9% of the total bilateral ODA to 1% (Table 1).

Table 1 Proportion of New Zealand ODA to Sub Saharan Africa

Source: OECD (2014), plus data provided by MFAT

Source: OECD (2014), plus data provided by MFAT

It is not surprising that New Zealand is now nearly disconnected from Africa. The National Party came to power in 2008 with a desire to re-direct most aid to “the realm of New Zealand”, as its parliamentary inquiry called it in 2010. Overall, these changes have been well documented in this NZADDs working paper [pdf].

What is a surprise, however, is that a closer look at New Zealand aid to Africa reveals that the gradual cutting of ties with Africa has not been a particular objective of conservative National Party governments since 2008. New Zealand’s disengagement with Africa was actually initiated and steadily implemented by successive Labour governments in the preceding years from 2005 onward.

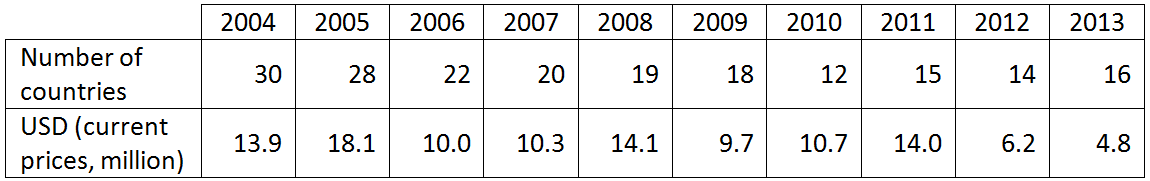

The second feature of New Zealand aid to Africa over the last ten years is – not unsurprisingly – that the number of countries with whom New Zealand maintains relations has been halved from 30 to 16 countries, as the dollar value of aid also drops to USD 4.8 million (Table 2).

Table 2 New Zealand ODA to Sub Saharan Africa: countries and volume in USD (million)

Source: OECD (2014), plus data provided by MFAT

Source: OECD (2014), plus data provided by MFAT

Obviously, there is the argument that a small volume of ODA spread over 30 countries leads to fragmentation and selectivity. However, these problems are overcome – without loss of networks or knowledge – by adhering to OECD principles of harmonisation and alignment, or by supporting regional programmes.

The third feature of New Zealand aid to Africa is that the minimal and diminishing amounts are mostly spent in richer and/or more stable countries. Eight of the 16 countries with whom New Zealand maintained aid relations in 2013 are ranked as ‘very high’, ‘high’, or ‘medium’ on the UNDP’s human development index or as stable states (i.e. Tanzania and Kenya). These eight richer and stable countries also receive 60% of New Zealand’s aid for Africa.

New Zealand aid to Africa has nearly ceased. What little remains is going to places where New Zealand companies have a commercial interest. For example, in funding for a Kenyan geothermal company, or for a public-private partnership with New Zealand companies in avocado oil production in Kenya. It succinctly embodies the current government’s desire for an “alignment of trade and aid policies”.

After a decade of Labour and National governments, New Zealand has re-directed its aid programme to become a bigger player in the South Pacific – in support of commercial interests. Conversely, New Zealand aid pulled out of Africa – with its fragile states and challenging environment of extreme poverty.

This disconnect from Africa has not only been at the level of official aid. New Zealand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs also ‘motivated’ NGOs in 2011 to close their African programmes. In contrast, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs ‘encouraged’ in 2011 a consortium of four Dutch NGOs to increase their operational presence and establish a ‘knowledge network’ in six fragile states in Africa by offering them the equivalent of NZD 99 million.

Arguably, New Zealand risks impairing its capabilities as an international player in various spheres.

In the diplomatic sphere, New Zealand risks losing its reputation as a knowledgeable international player. Its ambitions to participate on the international stage, for example in its current bid for a seat on the UN Security Council, will come to naught if many or major players think New Zealand has no expertise or networks where it matters. As one analyst noted: “The United Nations Security Council, 60 or 70 per cent of the business if we get on it will be about African peacekeeping or African conflict resolution.” Right. What does New Zealand bring to this UN table?

In the commercial sphere, New Zealand risks marginalisation at two levels. First, a loss of diplomatic and development cooperation with the world’s more active powers in Africa will eventually affect international trade cooperation too. Bad news for ”a country ever-hungry for more trade deals” – as one business-minded editorial noted. Second, as is China today, so too may be Africa tomorrow. MINT countries are replacing the BRIC countries as the economic giants of the 2020s. Nigeria, as the MINT’s ‘N’, is becoming the continent’s powerhouse. As things currently go, New Zealand’s business people will be Johnny-come-latelies in Africa in 2025.

Finally, in the sphere of development aid, New Zealand’s aid professionals risk being reduced to roles of travelling sales representatives in the South Pacific, who would be out of their depth when confronted with poverty in a region where neighbouring fragile states will affect their business – as it did in Kenya in 2013.

As New Zealand leaves Africa, New Zealand impairs itself. When the UN waves us in, when opportunity knocks at the door, or when the proverbial hits the van; New Zealand may not see, hear, or duck.

Gerard Prinsen teaches at Massey University and at Victoria University, concentrating on project management, aid policies, participatory research, and decentralised education and health services. Before coming to New Zealand in 2003, Gerard worked as manager, trainer or researcher for Dutch development agencies in several African countries, including an appointment as Dutch Honorary Consul in Mozambique.

Leave a Comment