This year, 2021, marks ten years since I started teaching at the University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG).

Regardless of what kind of state it is in today, UPNG’s history and continuity fascinates me. As a student of politics, I look to the institutions of PNG when trying to understand the process of nation-building. National institutions and landmarks are permanent fixtures in national narratives and tangible realities to all generations.

Several years ago, a commentator on one of PNG’s popular Facebook discussion groups posted an anecdotal survey. He requested respondents to rank in importance PNG’s celebrated national icons. What he had in mind were PNG’s famous political leaders. His list comprised current Members of Parliament, former prime ministers, and past statesmen. For me, this is an erroneous way of celebrating our collective national memory. Human personalities, with their imperfections, are not the appropriate embodiment of any national narrative. Their deeds may be exaggerated and future generations may end up with misconceived notions of the actual lives of these characters.

Think about the controversies surrounding some of the Founding Fathers of the United States. Thomas Jefferson may be an American icon, but to millions of American citizens of African descent, he was a slave-owner, who did not practice the high ideals he wrote about.

For this country, UPNG is an enduring institution. Countless generations of Papua New Guineans will continue to use it. Their knowledge and appreciation of the university will depend on their receptiveness to its history and place in our nation. This is the very same space that was once graced by the likes of Narokobi, Kiki, Jawaodimbari, Kaputin – some of the brilliant minds and architects of the nation. The university has a long tradition of infusing critical voices into national discourse and protesting unpopular government decisions.

For instance, the popular Waigani Seminar series was truly regional and global in its appeal. Student-led movements in the university also reflected a growing consciousness of PNG’s place in the region and beyond. A case in point was the nuclear free Pacific and decolonisation agenda of the Melanesian Solidarity movement. Much as it has since its inception, the university must continue to play its nation-building role, a constant physical reminder to future generations of where we came from and where we are headed as a nation.

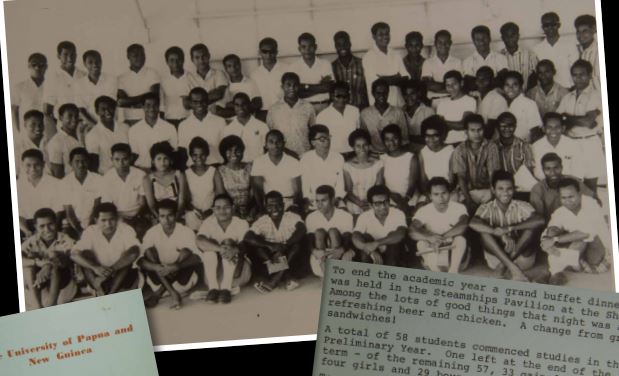

The creation of UPNG was a result of a series of recommendations contained in the so-called Currie Report of 1964. The nation’s first university was to facilitate the localisation process of Papua New Guineans in public service. More importantly, the university became a space for young Papua New Guineans to interact.

From the far-flung corners of the soon-to-be-independent nation, young Papua New Guineans converged onto campus, staying for extended periods of time away from their communities, building relationships that became important cornerstones of the early leadership of this country. Some of the first students at this university had barely been out of their villages or provinces of origin.

UPNG was not only the hub of intellectual pursuit, but earlier on it became the mediator of PNG’s socio-cultural diversity. In the infamous Port Moresby riots of July 1973, where the ugly face of inter-territorial antagonism between New Guineans and Papuans was witnessed, UPNG students became mediators in the riots when they created the Melanesian Action Front and staged a “peace and unity” march through the streets of the capital.

At a personal level, the university is the place where my parents first met. From different provinces in PNG, my parents came to study at UPNG, and ended up marrying, resulting in me being born. For many Papua New Guineans, UPNG is intertwined in their own personal life stories.

Commentators continuously make the case that the process of nation-building remain a challenge in PNG. Hugh White and Elsina Wainwright observed a while back that “the absence of a sense of nationhood is the foundation of many of Papua New Guinea’s problems”. Sinclair Dinnen has also argued that PNG’s law and order problems are in part a result of the lack of any “sense of common identity”, in a country that had a “relatively short and uneven experience of central administration”. We are said to possess linguistic and socio-cultural complexities, even the absence of any shared pre-colonial history or mythology.

To deal with this dilemma, White and Wainwright even suggested that nationalism be fostered through having a national rugby league team in the Australian National Rugby League. Knowing Papua New Guineans’ passion for the sport of rugby league, a national team would instil national pride and nationalism – so the argument goes. But is a rugby league team the best medium for communicating the nation’s narratives across generations?

A program aimed at documenting and restoring our foundational national institutions and landmarks is important for education purposes. There are success stories in the restoration of national icons and institutions of value to PNG. The National Museum and Art Gallery (NMAG), with support from Australian aid, successfully initiated a refurbishment exercise in 2018. According to its Director, Dr Andrew Moutu, the “NMAG remains a source of national pride for Papua New Guineans as the country’s leading cultural institution”. Other examples of national institutions with enduring relevance include the PNG Institute of Public Administration (Administrative College), Sogeri National High, Sir Hubert Murray Stadium and others.

The challenges facing UPNG are well-documented, and the divisive elements of regionalism or provincialism constantly threaten to destroy its reputation as a national “melting pot”. But if it is to remain relevant, the university should be treated, and should treat itself, as a national asset worth protecting, and not just some milking cow, employer of convenience or a place for the mass-production of degree qualifications. The university’s national significance makes its reform and restoration all the more urgent.

Disclosure

This research was undertaken with the support of the ANU-UPNG Partnership, an initiative of the PNG-Australia Partnership. The views represent those of the author only.

Leave a Comment