In part one of this series of posts, I examined the considerable role that scholarships play in the Australian aid program and highlighted some important questions around effectiveness, recruitment and value for money. Here, I share some initial results of the research that I have conducted into scholarships in three African countries: Kenya, Mozambique and Uganda.

To its credit, in the 2012 round of the Australian Development Research Awards Scheme (ADRAS), the Australian aid program called for applications focused on scholarships. Along with colleagues, I secured funding to examine scholarship outcomes for recipients in Kenya, Mozambique and Uganda. While the research was funded by DFAT, the research team was independent and the findings and views expressed here are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the Commonwealth of Australia.

My perspective on scholarships was driven by my own experience teaching scores of “AusAID scholars” as they were known, and still call themselves (despite the recent name change), in the Masters of International Public Health program at the University of Sydney. In general, the scholarship beneficiaries have been wonderful students who have contributed tremendously to our program and the education of their peers. They have been some of the most dynamic, intelligent, thoughtful students I have encountered in my ten-plus years of interacting with university students.

I have stayed in touch with many of the students and noted that while some did fantastically well on their return – shooting up the ranks of their ministry in many cases – others struggled to settle back in professionally and personally. This seemed to me to be due to gender differences, whether the individual worked for the public sector (as opposed to the non-government or the private sector) in their home country, and the development status of their country. We wanted to see if these anecdotal reasons were just that or if they represented something more.

As part of our ADRAS project, we conducted an internet-based survey among individuals from Kenya, Mozambique and Uganda who graduated in 2000-2012 and studied for a masters level qualification at an Australian university. In addition, we conducted qualitative interviews with scholarship alumni from those countries who graduated with a health-sector degree from an Australian university. Full findings from the quantitative survey will be available soon.

We received 111 responses to the 373 valid email addresses that we sent the survey to (30% response rate[1]): 40% from Mozambique, 36% from Kenya and 24% from Uganda.

Overall, the results from the survey and interviews paint a very positive picture of scholarships. Of course, the respondents are biased by the fact that they themselves have been beneficiaries of the program. Those who responded are possibly more likely to be the ones who felt that they got the most out of the scholarship program, while those who did not thrive or did not enjoy the experience might have been less inclined to respond. Such cases of respondent bias and social desirability bias are common in these types of surveys. Nevertheless, of those alumni who did respond: their impressions of Australia, what they had learned, and their experiences on their return were very favourable.

When participants were asked to rate how they felt about Australia on a scale of one to five – where five was ‘most positive’ and one ‘most negative’ – 83 (81%) respondents felt most positive about Australia, followed by 18 (18%) who gave a rating of four. No participants rated how they felt about Australia as lower than three out of five.

By and large, respondents believed that their scholarship had contributed to positive change in their community, place of work or country. A majority of respondents received a promotion (82%), an increased salary (83%), supervised more staff (76%), had greater financial responsibility (74%), had greater technical responsibility (87%) and had a greater role in policy making (77%). In general, most participants identified their scholarship as an important contributing factor to their increased workplace responsibilities and remuneration. The vast majority of respondents (84%) felt that the content, knowledge and skills they gained during their award studies were highly relevant to their current job.

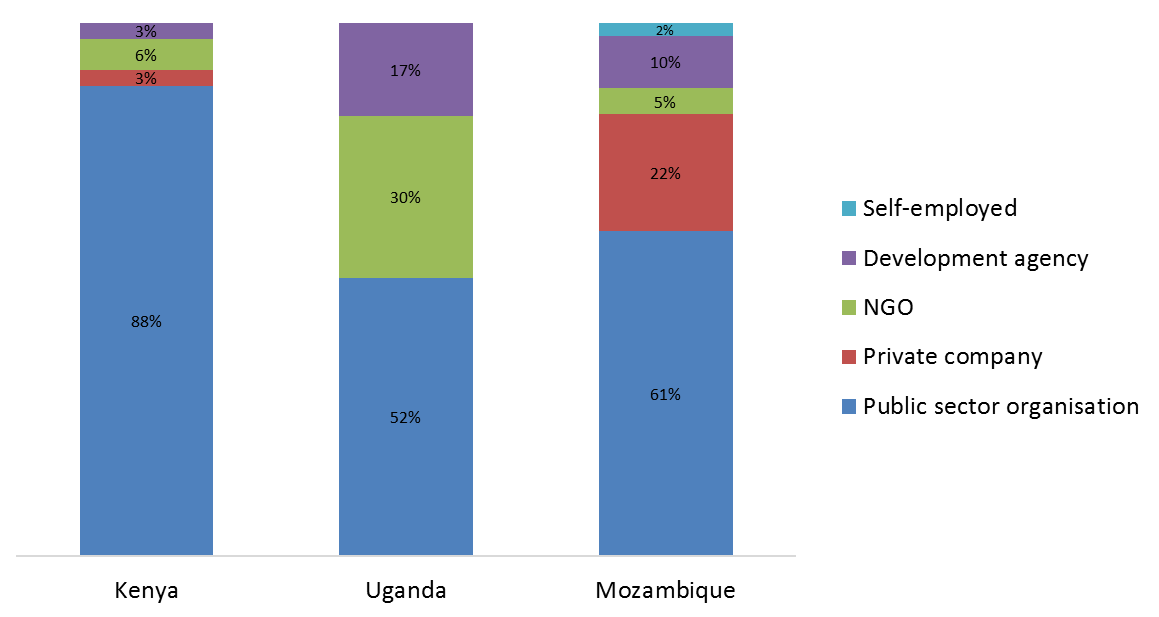

Responses to the survey showed very different scholar selection approaches. Almost all Kenyan respondents were nominated by their employer (the government of Kenya) while only 7% of Mozambican respondents were nominated by theirs. Related to this, all Kenyan alumni came from the public sector, compared to about two-thirds of respondents from Uganda and Mozambique. This stems from bilateral aid agreements between Australia and the governments of those countries; where different scholarship recruitment models were agreed upon.

In addition to the above, 82% of all respondents returned to their employer after the scholarship – some were bonded and some were not – and two-thirds were still working in the public sector.

Current employer

Overall, 86% of respondents were still living in their home country. Only 5% had returned to live in Australia, and 4% were living elsewhere in Africa.

Overall, 86% of respondents were still living in their home country. Only 5% had returned to live in Australia, and 4% were living elsewhere in Africa.

Despite the favourable impression, ongoing links to Australia were poor. Alumni were not in contact or working with Australian academics or institutions, though they remained in contact with other scholarship alumni in their own country. This represents a significant loss of opportunity, especially given that building linkages is a key objective of the program.

We endeavoured to ascertain whether those who received Australian government scholarships were members of their country’s ‘elite’ or whether the scholarships were awarded to individuals who would not have otherwise had the opportunity. While this is difficult to assess in a quantitative survey, we used a proxy question: the highest level of education attained by either parent. The responses give a sense of prior opportunity and some sense of the socio-economic background of the individual. The results showed that Ugandan respondents were much more likely to have a parent whose highest attained level of education was tertiary (64%) than Mozambicans (28%) or Kenyans (22%), whilst Kenyan respondents were more likely to have a parent who did not have any kind of education.

Initial findings from the qualitative interviews (our analysis is not yet complete) suggest that the recipients themselves see the scholarship experience as critically important to their intellectual development and career progression. At the same time, hearing their stories, it was clear that many of the individuals were already quite accomplished before the scholarship and it is perhaps not surprising that they succeeded subsequent to their time in Australia. When asked, it was difficult for many of the individuals to attribute their achievements to their time in Australia.

Many alumni highlighted not the technical skills gained during the scholarship – which many asserted that they could have learned anywhere, including domestically – but rather the soft skills and attitudes that they developed by spending substantial time in the Australian context. The ‘soft skills’ that the alumni highlighted included professionalism, attention to detail and cross-cultural learning. They also remarked on seemingly “little” things, such as buses running on time with friendly drivers, as key points of difference and elements that allowed them to advance their careers.

Based on these initial findings, part three in this series will include some personal thoughts on future directions for the scholarship program.

This is the second post in a three part series on the effectiveness of scholarships in the Australian aid program, collected here.

Joel Negin is a Senior Lecturer in International Public Health at the University of Sydney.

[1] This response rate is similar to comparable studies by the World Bank (19% response rate) (World Bank Institute. Joint Japan/World Bank Graduate Scholarship Program (JJ/WBGSP). Tracer Study VIII. 2010) and the Canadian International Development Agency (21% response rate) (Canadian International Development Agency. Evaluation of the Canadian Francophonie Scholarship Program (CFSP), 1987-2005. December 2005 [pdf]).