Last week I asked the question, ‘is economic development an appropriate core focus for an aid programme?’ It’s a big question so, to answer it, I broke it in two, focusing last week on whether economic development leads to improvements in the things that really matter, like poverty-reduction and health. The answer being yes – more or less.

“Yes,” because on average across countries economic development is associated with better outcomes in these areas. “More or less,” because there’s considerable variance around those averages. Some parts of the world have done much better than others in turning wealth into health and reduced poverty. And some countries have managed to achieve respectable outcomes despite not being particularly wealthy.

Nevertheless, the average impacts alone provide a pretty good case for focusing aid on economic development — if aid can be shown to be an effective tool for bringing it about. The case is stronger still when one considers that economic development ought to ultimately contribute to countries becoming independent of aid (being wealthy enough to fund their own social programmes). Given the capriciousness of aid donors, this has to be a benefit.

Yet even if economic development is a good thing, there’s no point focusing aid on it if aid can’t bring it about. Which leads to my second question, ‘is aid an effective tool for promoting economic development?’

The good news for those of us seeking answers on aid’s impact on economic development is that this is something that economists have been studying avidly for decades now, making use of the most sophisticated tools of their trade. Unfortunately, the bad news is also that this is a question that economists have been studying avidly for decades now, making use of the most sophisticated tools of their trade.

So our question has an answer, but it also has another answer, and another. Some studies find aid having a major positive impact on economic development, some find it having a small positive impact, some find it has no significant impact, and some find it having a negative impact.

The problem here is that the primary tools that economists have used in their examinations have been cross-country growth regressions. These seem like an excellent tool for measuring aid’s impact on economic development, and they do provide apparently authoritative results. But when you take into account the vast number of potential control variables, the patchy (and often inaccurate) data, the inadequacy of available instruments for dealing with reverse causality, and the lack of any particularly good way of distinguishing good aid from bad, what you’ve actually got is a fraught tool. And also a tool that can be put together in all manner of ways, which partially explains why it’s produced all manner of results. (For a good discussion of some of these issues see here.)

For what it’s worth, of the two most recent high-profile studies of the aid growth relationship, one (Rajan and Subramanian – gated/ungated) finds no statistically significant relationship and the other (Arndt, Jones and Tarp – gated/ungated) finds a small positive relationship.

This is not a particularly heartening result. However, it’s not evidence – despite what aid’s critics may claim – that aid doesn’t work.

First, if Arndt, Jones and Tarp are correct and the impact of aid is small but positive, this isn’t to be sniffed at. Over time even small improvements add up.

Second, the underwhelming findings themselves may simply be a result of the methodological challenges of aid growth regressions. Indeed, both studies have already been critiqued (see here and here). Although the underwhelming regression findings are lent credence by the absence of any compelling examples of aid having transformed the economic fortunes of particular countries.

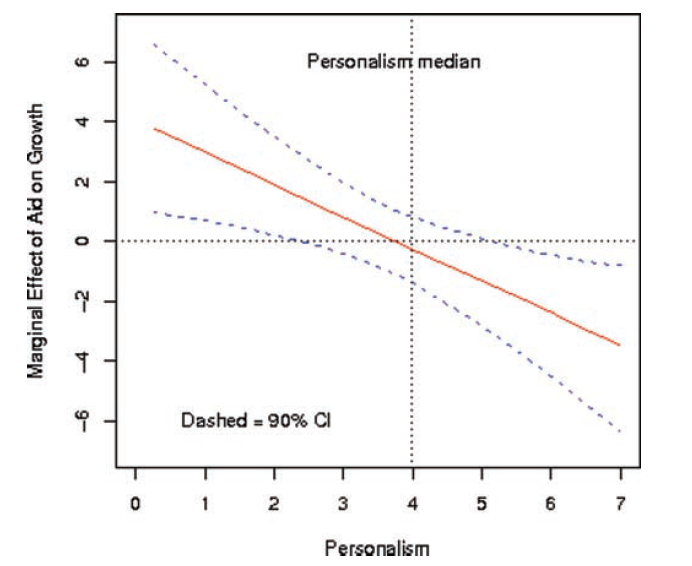

Third, aggregate findings of a small or non-significant relationship between aid and growth may themselves mask the differing impact of aid in individual countries. This possibility has been tested for previously using governance indicators but with the results typically being found to be insignificant or methodologically wanting. However, one recent study by Joseph Wright (gated link here) appears to have revived the fortunes of such work, apparently showing that the impact of aid on economic development varies depending on the political characteristics of recipient countries. It’s a chart from this paper that heads this post. If the paper’s findings are correct (and they may not be) aid has a significant positive impact on growth in countries with political systems that are only weakly personality driven, while its impact in personalist polities is negative.

Fourth, even if aid isn’t effective in promoting economic development there’s good evidence to suggest that aid does work in other areas, at least in certain instances. In fields such as health and education aid has had successes. Not always, but it’s helped in some countries make schooling accessible, has rid the world (or nearly rid it) of illnesses like Small Pox and Polio and helped with a range of other health concerns. There’s some evidence to suggest aid has succeeded in areas such as democratic strengthening too.

The third and fourth points above are the crucial ones. Developing countries may all be poor, but they are not all alike. One only has to contrast the culture, political economy, geography and industry of India and Tonga to see this. And aid isn’t so powerful a tool that it will be able to perform the same tasks everywhere. Given this, and given that there are numerous means through which aid may potentially meaningfully improve people’s lives, it is a mistake to limit that potential through a restricted focus. Far better to make decisions based on context, on need, and on what aid might potentially be able to do.

In general, at least for poor countries, economic development is good. But development is difficult and aid can’t do everything – in such circumstances mandated myopia is mistaken.

Terence Wood is a PhD student at ANU. Prior to commencing study he worked for the New Zealand government aid programme. These blog posts are based on a working paper he wrote for New Zealand Aid and Development Dialogues. You can read it here [pdf].

Hi Alec,

Thanks for your comment, and good to hear from you. Could you post a link to the ODI paper? I would be very interested in reading it, as the findings sound quite different from those in most the studies of economic growth and poverty reduction.

The chart from the Kraay paper, which I discussed last week, provides a bunch of examples of growth episodes being associated with poverty reduction (all those dots in the bottom right quadrant). The chart is here: https://devpolicy.org/should-aid-focus-on-economic-development/poverty-growth/

It’s not just neoliberal’s who are pro-growth, it’s almost everyone from the neo-liberals to their critics like Stiglitz, Rodrik and Wade. And this is for good reason, in very poor countries, economic development really does seem to be associated with improved welfare. As I wrote last week, it’s not everything and it’s not the only thing but, on average, it helps.

Poverty and inequality are not the same thing. There are some good reasons to be opposed to high levels of inequality but it’s still possible for unequal countries to reduce poverty through growth.

It looks like you are considering both developed and developing countries. However, it is still worth asking (as this is what really matters here) is ‘Where in the developing world has economic growth led to poverty reduction?’ The most industrialised country in Africa, South Africa, has the highest inequality rates, globally (Gini co-efficient… seemingly exchanging this unfortunate ‘top-slot’ with Brazil every time these figures are released). In any case, what you are suggesting is essentially the history of so-called ‘development’ in the post-war era (eg US Pres. Truman’s address). It is modernisation theory…industrialism for growth and poverty reduction. But as you seem to indicate in your paper, many economists are firm believers in neo-liberal models to lift countries out of poverty, despite a lack of evidence linking economic growth to poverty reduction, as pointed out in a recent ODI paper.

oh and a couple of papers for those interested in quantitative analysis of aid effectiveness.

“Aid and Growth: What Meta-Analysis Reveals,” Tseday Jemaneh Mekasha and Finn Tarp:

http://www.wider.unu.edu/publications/working-papers/2011/en_GB/wp2011-022/

I think meta-analysis does little more than aggregate the problems of individual aid/growth regressions, but, nevertheless it’s interesting to see the much touted Doucouliagos and Paldam findings being challenged.

Also, “The Politics of Public Health Aid: Why Corrupt Governments Have Incentives to Implement Aid Effectively” Simone Dietrich, World Development Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 55–63, 2011, Gated link here: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X10001166

Which looks to be a very interesting example of certain types of aid working well in environments when others struggle.

Thanks Owen – I definitely agree, the interesting question is “‘which’ aid works and for what”?

And – consistent with what I’ve said above – I think it’s the height of folly to focus an aid programme on economic development when we don’t really know which aid does work for what. Far better to keep our options open at a mandate level, I think, and then let context, experience, research and M&E drive what we do.

I’m not a great fan of cross country growth regressions, whether they are used to ‘prove’ or ‘disprove’ the effectiveness of aid.

But if I had to summarise the literature, I would say this: almost every time somebody reports looking for a linear relationship between aid and growth, they haven’t found one. Almost every time somebody reports looking for a non-linear relationship, they find a small but statistically significant relationship.

The interesting question is not ‘whether’ aid works but ‘which’ aid works and for what.