My research has an urban focus and I undertook my PhD fieldwork in the ATS settlement in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. My thesis is available online at the ANU open access theses collection.

During my PhD research, I discovered that academic writing is a difficult, long, and rigorous process because of the need to engage with scholarship, the review process, and because knowledge and expertise are contested concepts. I sought to share my research and ideas through various platforms available to me at the time. These included policy briefs and blogs (my favourite!), conference presentations, seminars, and panel discussions. When opportunities arose to write peer reviewed articles or book chapters I would grab them. These bite size portions of sharing allowed me to test some of my ideas and enabled me to boost my confidence. I also received important feedback that improved the thesis. These modes of sharing are an important part of the process of research itself.

The most challenging, and most fun, part of sharing my research was at the end. As my PhD drew to its end, I started to think about how to share this research with the people and community who had generously shared their knowledge with me. I was nervous. I had occupied a privileged position to write for so many years. I had pulled together and synthesised data – words, observations, maps, photographs, literature, newspaper articles, emotions, experiences, numbers and other data – into a body of work that actually drew on many people. Ultimately, however, I felt accountable for it.

Had I consulted all the necessary and relevant sources and literature? Did I act ethically? Will my research lead to conflict? Did I understand what people were saying to me? Had I interpreted them accurately? Did I portray people’s lives honestly? Had I reflected my own positionality, which may have shaped my values and my interpretations? Importantly, given time limitations, how would I work through the rather large document that the thesis had become whilst ensuring that it would be accessible.

In addition, my field site of urban Papua New Guinea is also an increasingly contested space. Increasing land values, evictions, legal battles, inequality and other social, cultural, political economic forces means that the research touches on important issues in Port Moresby. We also research during a time when social media like Facebook, Twitter and blogs have helped to break down the barriers between researchers, the general population, and research participants. Mainstream print media is readily available in Port Moresby and the population has a higher education level. All these mean that debates can be intense. In addition, I am not an outsider to the fieldwork site. I lived in Port Moresby for a long time and have family and friends there who might be interested in what I had to say about home.

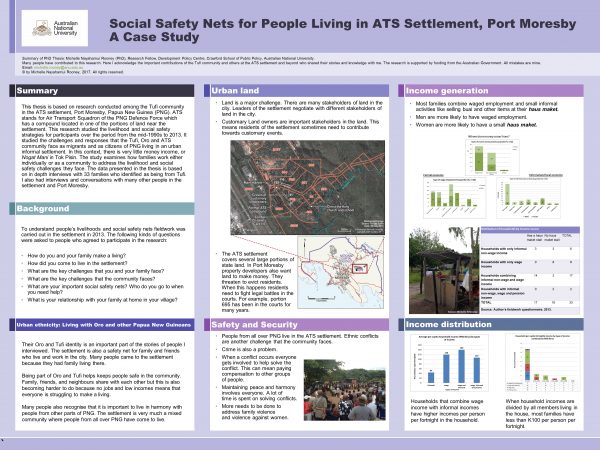

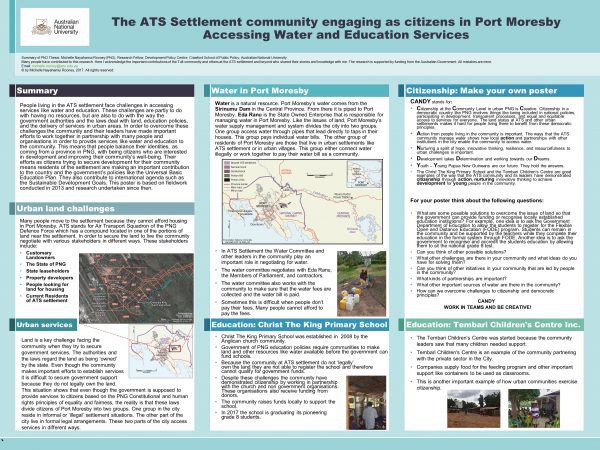

To assist in the process I prepared two posters (see posters 1 and 2 below) to summarise the research, and printed several hard copies of the thesis. Over two days in two different parts of the settlement, I made copies of the posters and the thesis available for people to browse. I explained the PhD process and apologised for the very long time it took to complete it and return to share it. I left three copies of the thesis and sets of posters with three leaders in different parts of the settlement for people to read in their own time.

Poster 1

Poster 2

Two days was not enough time for people to fully absorb the thesis and engage in its findings. It is likely that this process will unfold over the next few years. However, I was glad to note that some people asked me if they could use the posters and the thesis to engage with authorities as they strived to bring development into their community. Research and the knowledge it generates is a process that occurs between researchers and participants as well as with the broader panel of supervisors and advisors and the many people who engage with the researcher. One of the leaders reminded me about this point when I tried to apologise for any errors in the thesis. He had helped to guide and support my fieldwork. In response to my apology, he pointed out that the community had supported me by sharing their time, stories, and knowledge and therefore the outcome was our mutual responsibility.

One woman who was also an important collaborator who guided and supported the research asked an important question: “What’s next?” This question lingers with me and I am sure with her. It brings home the obligation we as researchers have to thinking through the implications and outcomes of our research. Without responding to this question, the research remains just a document. I like to think that it will generate conversations, add to the debates, and help people, including policy makers, think through the issues in the thesis. However, I do still think about how I might more concretely respond to my collaborator’s question.

Not everyone gets the same opportunity to return to host communities to share research. I am very lucky that I have a job that enables me to return to PNG and hence to the community. But, even without such a job, I feel that we live during a time when the internet, social media, platforms like blogging make it much easier to make research available to the wider public. I also shared the research with the National Research Institute, colleagues at the University of Papua New Guinea, and the funders of the research.

I decided to make my thesis available online. It is by no means perfect, and I remain circumspect about how the findings may shape debates and impact on the community, as Port Moresby continues to change rapidly. At times I feel overwhelmed by the thought that my research is now available publicly, but I am more confident after returning to the community.

I encourage others to reflect on how they want to share their research. Being open with communities and participants about the nature of research, the power you hold, and your own limitations in representing research is important. Communities and individuals are very generous when it comes to supporting research, and we need to be accountable to them. We also live in a time when the divide between researchers and researched is increasingly blurred.

Post-PhD, my researcher and personal identity are in many ways entangled and constantly changing with life and relationship changes. For me the sharing process is an important part of being accountable and acknowledging that our research outcomes are grounded in collective efforts. The process is not over. Completed research also takes on a life of its own as researchers, communities, other stakeholders, and the wider public begin to engage with the ideas, findings, and debates. This is the organic and mutually constructed nature of research.

Nice piece. I have thought about the exact issue – sharing my research findings with the study participants, and have started sharing my findings as short public health information on my Facebook page. Thanks a lot.

Thank you Dr Rooney for this interesting blog post.

I also shared my PhD findings with the people of the two key villages in Madang Province of Papua New Guinea where I conducted my research. For each village, I printed a bound version of the thesis and also asked the printers to create a hard cover box for the thesis in the same colour, to protect it in the village setting. I also took and left in each village the various publications, newspaper articles and so on that had mentioned the research. In each village, I gave an oral presentation, explaining the process and the findings in Tok Pisin, and introducing and passing around the various materials.

The villagers were delighted that I had “brought the name of our village to the world”, as they said it in Tok Pisin. I think they were thrilled to see their ideas and photographs of the village in print.

Thanks again for this blog post. I will share it with the students in the research methods course that I am currently teaching at the University of Papua New Guinea.

Dr Amanda H A Watson

Really interesting reflections on an often-overlooked part of the research process: returning the findings to those they came from. Thanks for your open and honest sharing about challenges, positives and principles of this process. It’s something close to my heart as a researcher and helpful to learn from how others have approached this.

Thank you Alice. I hope it helps. The more people I speak to I realise that this is something many researchers think about so it’s good to know we are not alone.

Brilliant Michelle, many thanks for sharing this solution. I too have agonized about whether I have my Zambian mining mining impact research story right and how to share the findings to those involved who are not big readers. It also picks up on an aspect of a paper I wrote for the last Dev Bull, No. 79, Jan. 2018, about the problems of research. This inspires me to do some more work on this aspect when I finally finish the seemingly endless editing.

Thank you Margaret. It was interesting to read that some of the challenges you discuss in the Zambia context- research fatigue, helicopter researchers with preconceived ideas, and over researched communities – resonate with the PNG context. Thank you for sharing it.

Thanks for sharing this article. As a researcher myself posters are always an effective tool for sharing ones research. Did you translate the posters into the local language? From my experience in presenting posters, large blocks of text in posters tend to stifle passers by. If they are confounded with any statement or diagram they will stop viewing the poster. Simple annotated diagrams are key (the ones in your poster are excellent). Was the poster that you presented to the community a toned down version of one that would be used at a conference? As a last point, can you share where you obtained the Port Moresby GIS maps? Thanks in advance.

Hi Oliver,

Thank you. I agree with you that simplicity is best. Glad you like these ones although I do wish I had the time to translate it as well as more time to workshop the research findings. I left several copies with different people and at the school and hope they will be used.

I also left lots of paint and canvases at the school and hopefully the students might do some of their own posters – this, I would have loved to spend more time with. The Port Moresby GIS maps were prepared by the very excellent ANU CartoGIS team. Cheers, Michelle

Tankyu tumas Michelle for candidly sharing about your PhD research process and the importance of closing the loop with those who were part of that collective journey. The perseverance and considered approach to working with our Melanesian communities is an inspiration to us all. Looking forward to seeing more from you!

Thank you Anna for your kind words. Still so much more we researchers can do to share our research with communities. Tenkiu tru