Can our wireless gadgets, our vibrating, buzzing, whirring tools, transform democracy? Lead to good governance? Motivate transparency or support humanitarian response? Or is the idea that our weapons of the wired are a digital game-changer going to prove so much empty tweet: 140 characters of nothing much at all?

For somebody who has spent so much time online, stewarding websites and monitoring the comings-and-the-goings of the electronic ether, I am not your standard digitopia sceptic. But when it really comes to the crunch, I have become an unlikely advocate for the idea that whatever the merits of our socially-networked world there is, at least in a place like Myanmar, much good reason to think of old fashioned tools first and foremost. I have in mind things like shovels, and pens, and stethoscopes, and garbage cans, and, yes, guns.

For now, the mobile and Internet revolution remains tentative in Myanmar, with every chance its implications will not lead to the types of positive outcomes that we tend to have in mind.

To put these comments in their right context, let’s begin with some quick history. I recall a very recent time when the only way to regularly get “international” news in Myanmar was to get your hands on over-priced copies of Thailand’s Nation or Bangkok Post. Of course you could also entertain yourself with what was often a scratchy image from the official television news. Men in uniform were, and remain, standard fodder. In those days a mobile phone in Myanmar was typically a tycoon’s toy, the exclusive preserve of millionaires and their minions. Priced in the thousands of dollars, the government had no interest in proliferating a technology which, they feared, would help mobilise street mobs and lead to the anarchy of the masses. Instead, the country’s flimsy mobile phone system was designed with a certain isolationist and unconnected nonchalance.

To put these comments in their right context, let’s begin with some quick history. I recall a very recent time when the only way to regularly get “international” news in Myanmar was to get your hands on over-priced copies of Thailand’s Nation or Bangkok Post. Of course you could also entertain yourself with what was often a scratchy image from the official television news. Men in uniform were, and remain, standard fodder. In those days a mobile phone in Myanmar was typically a tycoon’s toy, the exclusive preserve of millionaires and their minions. Priced in the thousands of dollars, the government had no interest in proliferating a technology which, they feared, would help mobilise street mobs and lead to the anarchy of the masses. Instead, the country’s flimsy mobile phone system was designed with a certain isolationist and unconnected nonchalance.

The Internet wasn’t much better, with expensive, erratic connections quarantined to dingy hotel foyers and teenage-boy infested Internet cafes. The teenage boys, as anywhere, spent their time playing Counter Strike or one of the FIFA-inspired soccer games. Until, say, 2008, both the Internet and mobile phones were too expensive and too limited in their range to be taken seriously as popular and political tools.

That has changed very quickly and nowadays, all over Myanmar, you can pick up stray Wifi signals on every second street corner. Internet use has skyrocketed and somewhere between 5 and 10 percent of the population now have a mobile phone. They are relatively cheap, with prices comparable to the international norm, and the government has recently released batches of bargain basements SIMs, at barely a few dollars a pop. All of this is circulating through a telecommunications market that was almost non-existent even half a decade ago. People are justifiably proud of their new connections.

That has changed very quickly and nowadays, all over Myanmar, you can pick up stray Wifi signals on every second street corner. Internet use has skyrocketed and somewhere between 5 and 10 percent of the population now have a mobile phone. They are relatively cheap, with prices comparable to the international norm, and the government has recently released batches of bargain basements SIMs, at barely a few dollars a pop. All of this is circulating through a telecommunications market that was almost non-existent even half a decade ago. People are justifiably proud of their new connections.

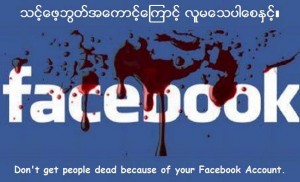

We should ask: what are they doing with them? Well, if you hang around in Yangon they’re on Facebook, at least the core demographic of 16-30 year olds. Constantly updating, friending, poking and all the rest: their efforts are part of a newly popularised effort to get online. Most of the traffic is of the flirtatious, gossipy, look-at-me kind, beloved of Facebookers around the world. When the big issues of the day, like ethnic political conflict, start to intrude on the Facebook scene, then the temptation is to get inside a partisan, sectional echo chamber. The Facebook system is designed to encourage this but at least in Myanmar, given the political history, the ramifications are not benign.

On Facebook, for instance, and depending on who you have as friends, your list might be peppered with the Kachin Independence Army flag; the default option for those wanting to trumpet their Kachin nationalist bonafides. The flag represents an ethnic sub-nationalist group that went toe-to-toe with the Myanmar armed forces from June 2011 to May 2013 in a war that probably killed 4,000 people. Kachin partisans on Facebook have made their feelings known. Yet such relatively subdued Kachin advocacy stands in some contrast to the situation elsewhere on the Myanmar Internet. When violence between Muslim and Buddhist groups has sparked over the past year, we have witnessed the unedifying spectacle of old hates running amok in fields of digital freedom. Nasty, vindictive and utterly anti-social talk spreads quickly, gets virulent responses, and ends in cycles of recrimination and unease.

With such matters echoing around my head I will turn to three analytical points worthy of future consideration.

First, there is the assertion that, overall, the Internet and greater connectivity, including through mobile phones, will ultimately have a positive influence. I accept this assertion, to a point. Since 2006 I have run a website that deals with sensitive political and social issues in the mainland Southeast Asian region. I’d like to think it has made a positive impact but I am aware that in many cases its role has not been judged benign. The challenge of these technologies is to harness their constructive and productive power. The ever-present danger is that they will be best mobilised and most rabidly deployed by those whose interests militate against democracy, accountability and humanitarianism.

Second, there are the negative influences that inter-connection can bring, and I have flagged those already for the Myanmar case. For its Internet denizens, festering sectarian or communal hatreds have been given new voice in the online sphere. If you spend your time trawling Burmese message boards then you get accustomed to the vitriol and hate. Of course it’s no different in Thailand, or Australia for that matter. The obliteration of moderate public space and its opportunities for critical, but considered, dissent is an online tragedy. Some people probably like to pretend that it doesn’t matter that hateful rhetoric, often anonymous, comes to dominate online. But I think it does.

Second, there are the negative influences that inter-connection can bring, and I have flagged those already for the Myanmar case. For its Internet denizens, festering sectarian or communal hatreds have been given new voice in the online sphere. If you spend your time trawling Burmese message boards then you get accustomed to the vitriol and hate. Of course it’s no different in Thailand, or Australia for that matter. The obliteration of moderate public space and its opportunities for critical, but considered, dissent is an online tragedy. Some people probably like to pretend that it doesn’t matter that hateful rhetoric, often anonymous, comes to dominate online. But I think it does.

Third, there is the link between these technologies and the array of political powers that seek to control them. In Myanmar the subversive potential of blogging, tweeting and texting kept the old military regime on a hair-trigger. The generals did, for a time, get in the habit of stalling the country’s Internet traffic, just to make sure that not too much anti-government material could circulate too fast. In the years ahead the idea that Myanmar’s Internet will be switched off will become a hazy memory to be replaced, in all likelihood, by the targeted blocking and sanctioning of specific web outputs. In Myanmar this may initially focus on pornography, but there is every chance that it will spread to other categories of content, including social and political criticism.

Finally, the challenge we all face online and in our lives today is that the Internet changes the equation for all political and social space. For a country like Myanmar the winds that will buffet its online shores will come from far away, including from the Qatari and Norwegian companies building the new telecommunication systems.

For those wishing Myanmar well as the country’s political and economic transformation continues, I think it is reasonable to share concerns about the Internet’s role. Developing cultures of considered online exchange and interaction is not easy and I think in a place like Australia we have tended to fail, with few exceptions, when it comes to raising the level of online discussion. Attacks on vulnerable communities online, especially women and minorities, are a deeply regrettable hazard of our Internet culture.

For Myanmar I am not convinced there is any solution to these imperfections, and that instead we may all need to come to terms with the destructive character of some 21st century inter-connectivity.

Dr Nicholas Farrelly is a Southeast Asia specialist in the School of International Political and Strategic Studies, ANU College of College of Asia and the Pacific. In 2012 he received an Australian Research Council fellowship for a study of Myanmar’s political cultures “in transition”. This article is an edited version of a talk presented at a recent Development Policy Centre seminar. The accompanying slides are available here and an audio recording of the event is available here.

The answer to your first question, of course, is “no”, tools on their own can’t transform democracy, just like a hammer on its own can’t build a house. It’s people using tools productively that do any of those things.

It’s not clear what you’re suggesting here – are you saying we should in some way try to restrain Myanmar from gaining access to the tools many of the rest of us use to improve our lives? Other countries can handle tech, but not Myanmar? Naturally, some people say nasty things online. Some people also use the tools for good. Since in Myanmar, some people stir up ethnic hatred in online forums, are you arguing that we should make sure the rest of the country doesn’t get access to these tools, because they might do the same thing?

Maybe I just wasn’t getting what your argument was, but what you present seems to be an argument for a more open discussion about the internet and more coordinated efforts to help people learn information literacy. Of course, everyone shares concerns about the internet’s role in everything these days. Of course it can be a tool for destructiveness. But the answer to that is fostering positive usage and productive online behavior. There’s no putting the genie back in the bottle.