In the Pacific region, only a handful of countries have embraced temporary special measures (TSM), that is, measures designed to increase women’s participation in politics. These include Samoa and New Caledonia. In Papua New Guinea (PNG), the Autonomous Region of Bougainville parliament has three reserved seats for women.

The topic of TSM has been on and off the political agenda in PNG for well over a decade, since 2009. The initiative has gone through the leadership of three different prime ministers: first Sir Michael Somare, followed by Peter O’Neill, and currently James Marape. This is the first of two blogs that map the TSM journey through a changing and often murky political landscape in PNG. Here I focus on the ups and downs of the journey to the end of 2019. In the second post I bring the story up to date, with continuing uncertainty surrounding TSM as the 2022 election looms.

PNG has, on paper, led the way in special provisions for women’s representation in decision-making bodies. The 1995 Organic Law on Provincial and Local Level Government (OLPLLG) specifies that women members be appointed to subnational-level decision-making fora – two for each rural local-level government (LLG), one for each urban LLG, and one for each provincial assembly. However, the law’s effectiveness has been limited by under-resourcing, power games, lack of commitment and poor leadership. Many LLGs and provincial assemblies have failed to appoint women to the special seats.

These appointed seats could have provided a strong platform for building grassroots leadership and meaningful engagement in decision-making by women at the subnational level, and this is a lost opportunity. To date, the impact of these early special measures has not been properly monitored and documented.

The Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare was supportive of the push for TSM in 2009. With Dame Carol Kidu as the minister leading the reform, the agenda was introduced as an option utilising Section 102 of the Constitution to appoint a small number of women to parliament. However, the change was not supported by the needed two-thirds majority of MPs. Soon after, with Somare’s ill-health and a lengthy absence for medical treatment, there was a change in leadership with O’Neill taking over as prime minister in 2011.

Shortly thereafter, the next attempt was made, this time to establish new reserved seats for women. The initial plan was to introduce 22 reserved seats, one for each of the 22 provinces, but the proposal was watered down and became a provision for “women’s electorates”, without specifying the number.

The Equality and Participation Act was passed by parliament and certified on 28 December 2011. Earlier that year, at the 27 May parliament sitting, Prime Minister Peter O’Neill made the following statement while presenting the Bill on Equality and Participation for debate:

Mr Speaker, more women in Parliament will bring more perspective to the House. We must start by ensuring that the voices of women are heard and represented here in Parliament. Mr Speaker, this Amendment Bill provide for a new category of seats in National Parliament. The National Parliament will now be comprised of the following members: open members representing an open electorate, provincial governors representing provincial electorates and women representing women’s electorates in the regional seats. (Hansard, 2011: 53)

Section 101 (1) of the new Act refers to “a number of women elected from a single-member women’s electorates as defined under an Organic Law”.

Although the Act was passed, the initiative faced stiff opposition, from the public as well as the political leadership. Both failed to understand that improving women’s representation in parliament is integral to good governance and democracy. Resistance from the political leadership was not a surprise. The earlier TSM campaign had the potential to have up to 22 women in parliament, a direct assault on male dominance in national politics. The enabling legislation required by the Equality and Participation Law was defeated in parliament in 2012.

After a long wait, the Constitutional and Law Reform Commission review of the OLPLLG in 2018 again brought the TSM agenda to the fore. Nationwide public consultations led to a fresh proposal to be considered by the government, still under Peter O’Neill. But in November 2019, a change in leadership saw James Marape become prime minister.

At a workshop supported by UNDP, and convened by the Integrity of Political Parties and Candidates Commission in November 2019, PM Marape clearly stated in his opening keynote address that his government did not believe in TSM as the way to promote women’s representation in parliament.

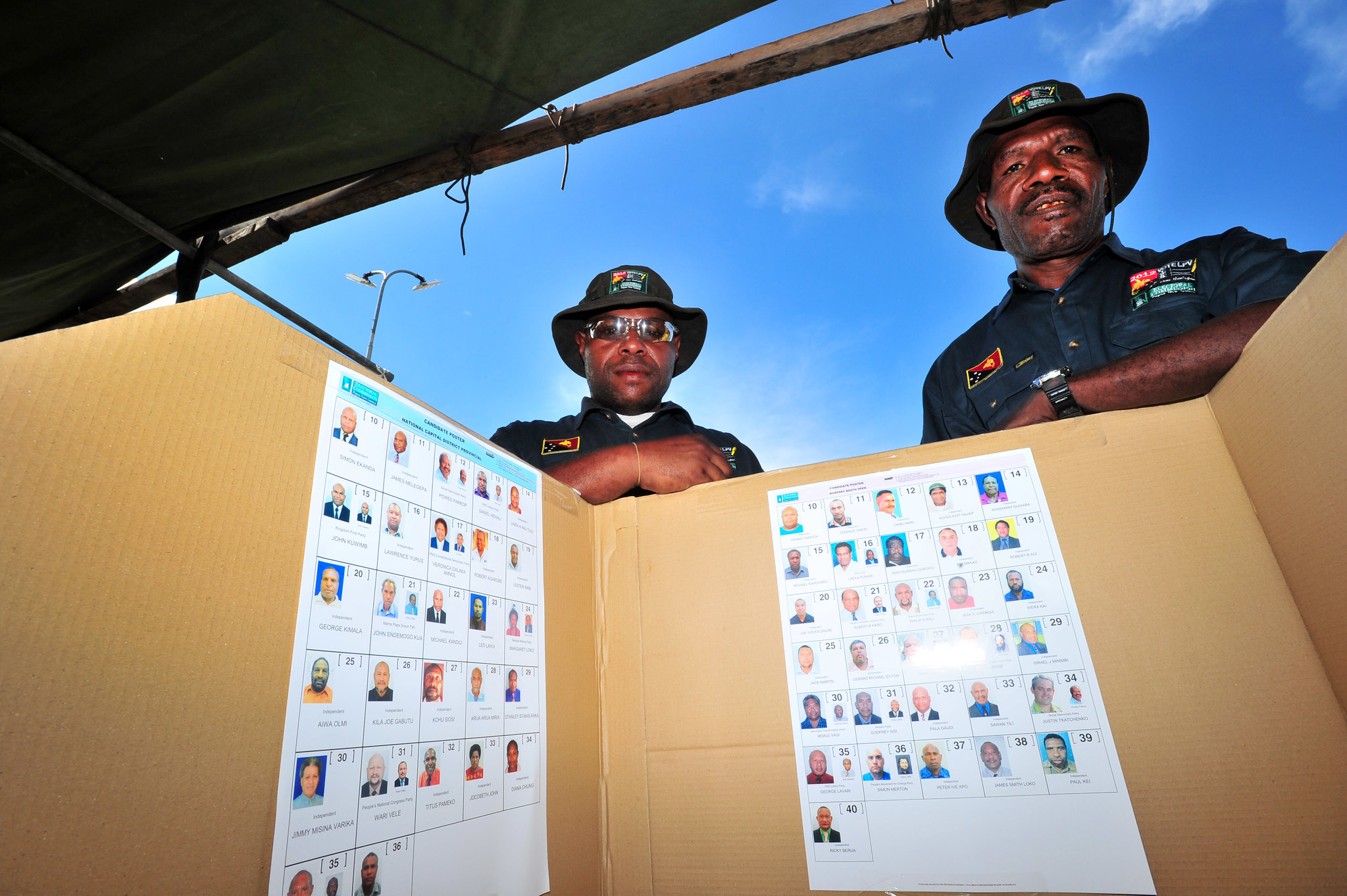

Marape’s approach, he said, was rather to address the uneven playing field by improving election administration so that women were elected on merit. But is this possible when election fraud and malpractice, and violence, especially in the Highlands region, have become entrenched in PNG elections?

Fortunately, it would seem, Marape may have had a change of heart. The next blog takes up the story.

This is the first blog in a two-part series on #Temporary special measures in PNG. You can read the second blog here.