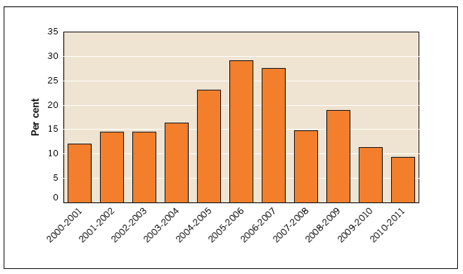

In 2003, Australian aid was in a state of flux. The Pacific seemed to be collapsing. Aid wasn’t working. Something new needed to be done. The solution was WoG, or “Whole of Government”. Private advisers were ineffective. Government officials would come in and fix things up. By 2005-06, the share of the aid budget allocated to departments other than the official aid agency, AusAID, has risen dramatically to 30%.

Today, those heady days seem a long time gone, as the graph below shows. The Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI) continues, but is being downsized. The other whole-of-government flagship, the PNG Enhanced Cooperation Program is a shadow of its former self. In 2010-11 departments other than AusAID spent less than 10% of the aid budget. Whole-of-government has been downgraded from the instrument of choice into a useful arrow in the aid quiver.

On Friday January 22nd, Foreign Affairs Minister Kevin Rudd released a new report, the APS (Australian Public Service) Adviser Review, or, in full the “Review of terms and conditions for Australian Government officials deployed as advisers under the Australian Aid Program”, completed in September last year. It follows a 2010 review of private sector consultant salaries, which in turn followed some high publicity cases of high-paid private aid-funded advisers. What these media stories never picked up on was that, no matter how much the private-sector consultants were paid, Australian government advisers were, on average, being paid more (as long acknowledged, for example, here).

It is to the Minister’s and AusAID’s credit that they took the lead in reviewing Australian government adviser remuneration, which earlier had been a matter left to each sending department. The report just out certainly reveals some very generous perks. Four in particular that stuck out to me were:

- A cash payment to Enhanced Cooperation Program (now Strongim Govman Program or SGP) staff in PNG equivalent to the cost of six return trips a year, compared to the entitlement for AusAID staff posted overseas to take one trip every two years (with no provision to cash the entitlement out).

- A $10-20,000 bonus for (non-AusAID) Australian government advisers working in Jakarta.

- The common practice of paying public servants at the next level up from their actual range.

- The provision of vehicles to Australian public servants, including for private use, at no charge.

The APS Review eliminates the last three of these perks, or at least recommends their elimination (I return to this distinction later.) Travel entitlements for SGP advisers in PNG are reduced from once every two months to three times in two years, still three times as generous compared to what most AusAID staff obtain (once in every two years).

There will always be those who complain that tightening conditions will make it harder for departments to attract the staff needed to work overseas. But conditions of overseas service are still very generous due to their tax free status, and a line has to be drawn somewhere. In my experience, many of those who work overseas really enjoy it, and are quick to queue for a second go.

While the APS Review is therefore a highly commendable step forward, three limitations also need to be recognized.

First, the review only covers a minority of APS advisers. Importantly, it does not cover staff serving with the Australian Federal Police, which is the source of many more overseas aid-funded advisers than any other department. According to its website, the AFP International Deployment Group has 450 staff deployed overseas. By contrast, according to the Aid Review there are only some 64 non-AFP public servants working as aid-funded advisers.

The review says this is because the AFP is covered by the Federal Police Act of 1979. But this sounds like a fig leaf. The AFP now has a monopoly on the provision of policing assistance through the Australian aid program. It should not be allowed to charge whatever price it likes. After all, the APS Review does not go to the issue of base salaries – the pay provided by sending departments to their domestic staff – but rather addresses only those perks (provided in addition to base salaries) associated with aid-funded, overseas positions. At a minimum, one would expect the AFP to be transparent and to set out the terms and conditions for its overseas advisers in the same way that AusAID and other government departments have now done in Attachment C of the APS review.

Second, there is only the briefest mention in the APS Review of that biggest perk of all: the tax-free status of adviser salaries. DFAT and AusAID staff typically continue to pay tax while they serve overseas. Why other government public servants shouldn’t (or shouldn’t be paid net-of-tax salaries) is not clear. Private-sector advisers also receive tax-free salaries, but have to compete for contracts, and now face salary regulation following the 2010 adviser review. I used to work for the World Bank, which also offered tax-free salaries, but at least the benchmarking of Bank salaries was against the net-of-tax salaries of tax-paying comparators.

Third, the nature of the report’s recommendations is unclear. Under each of the report’s seven recommendations is listed “Agency Feedback.” According to this feedback, agencies agree with most but not all recommendations. But what then is the status of the report? Is it, in the end, up to the departments to decide whether or not advisers should have to pay for the personal use of their vehicles, which seems to be one of the more contentious issues? Is AusAID not in a position to issue rules on perks for departments wishing to access aid funds, only guidelines?

This last point goes to the issue of the status of AusAID. Recently, AusAID was upgraded to an “Executive Agency,” one of only six. But Executive Agencies are normally very small outfits (the National Archives, and Old Parliament House are two of the other five). AusAID, by comparison, is one of the government’s biggest spending agencies. Why not make it a department, so that it is equivalent in status to the departments it is trying to pull into line? Making AusAID a department would enhance its status and authority, help give it the clout it needs to set the basic parameters for engagement by all departments and agencies in the aid program, and perhaps help eliminate in the future the sort of ambiguity evident in the status of the APS Adviser Review recommendations.

Stephen Howes is the Director of the Development Policy Centre.

Santif, This comment is completely wide of the mark. The proposal in the APS Adviser Review is simply that public service advisers who would not be entitled to a car in Canberra but who have been given one overseas would have to pay $250 a month if they make extensive private use of their vehicle. It would be left to individual agencies to decide whether cars should be allocated to advisers. If you want a meaningful debate, you need to be well informed.

I think there are a number of wrapped issues here but all I am concerned with at the moment is the PNG context.

– Firstly let me say that that the provision of a vehicle in Canberra is a very poor proxy for whether a vehicle should be issue in another country – you are comparing apples and oranges;

– Secondly – let me ask how do you define “extensive private use” – maybe going to the cinema (isn’t one) going for long country drives (not likely) ducking across to Lae (sorry the road doesn’t go across the ranges) nightclubbing (crazy if you do). Much is made of the provision of a vehicle as if it is some sort of massive fringe benefit when the reality is that it is an essential component of ensuring a secure environment..

The problem I have with this particular issue is not so much that people make a contribution to the private use of provided motor vehicles it is that this is the same stream of thought process that has seen the non-APS adviser community largely stripped of the provision of motor vehicles without consideration of the full implications. The debate is narrowly focussed without full consideration of the implications.

Well informed? Yes I wish some were!

Some elements of insanity regarding the discussion surrounding vehicles for advisers going to PNG;

You will pay at least twice as much for a comparable vehicle in PNG than in Australia. The environment and exchange issues mean that maintenance costs are highly inflated when compared with Australia and repairs can take much longer than in Australia (added vehicle hiring costs). Then add the risks of vehicle loss and litigious nature of the society means insurance and associated risk are disproportionately high.

Anyone considering a job in PNG should consider the above. Spending $10,000+ (anything less is a mobile coffin) upfront for a job with questionable security attached will come as a rude shock to many who have never been to PNG. Think also about how you will sell – if you can! And remember that these costs are additional to your existing vehicle wherever home is (unless you plan to play the buy and sell game there as well!).

I will not be surprised when someone gets killed because they tried to get around in questionable public transport system and paid the ultimate price – and just to put “questionable” into context we are talking vehicles that are not roadworthy, drivers who have questionable skills (may be unlicensed), drivers who have been known to be the perpetrators of crimes on passengers, telegraphing on movements to the criminal element and the list goes on. [This is not paranoia – this is the reality of living in POM and you are fooling yourself if you ignore it.]

What about hire cars – consider A$2,500 per month for an old second hand car on long term hire arrangements (probably a lot more by now). Short term hire A$150/day. These are rough estimates from some time back – but consider taking A$2,500 of your monthly salary and you might think twice about the decision to take the job.

There are a host more associated issues and the unfortunate aspect of the debate is that people who make criticism of the provision of vehicles and/or associated compensation in lieu too frequently demonstrate a distinct lack of understanding of the operating environment.

My suggestion – stop developing positions based on personal bias and undertake some true analysis of the situation then the debate can approach a meaningful level. Now let’s get real instead of emotional.