For some there was a lot of pain in the Australian federal budget brought down this week and anyone interested in a more generous foreign aid program would have been particularly disappointed. Statements by Joe Hockey and others, including the Prime Minister, that Australia should not be borrowing from overseas to send it overseas as foreign aid suggest that the cuts to the aid budget are a reflection of the government’s tight fiscal position. While this view will be the subject of a follow-up blog, it does signal that aid funding is in a new era. So how bad is Australia’s fiscal position?

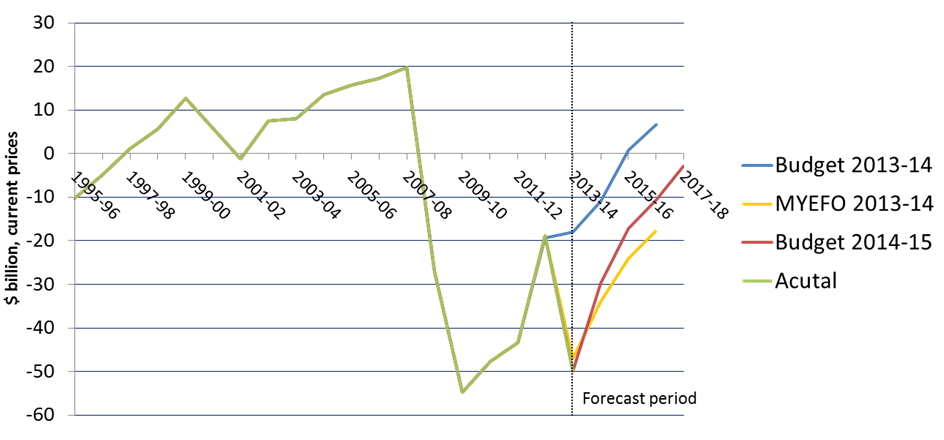

Figure 1: Underlying cash balance

The budget has been in deficit since 2007-08 and is projected in this year’s budget to remain in the red until at least 2018. This is indicative of significant structural issues with the budget both over the short to medium term, including the period covering the forward estimates, but also well beyond into the future. While many factors have led to the current fiscal position, the underlying problem has largely been driven by low revenue.

The budget has been in deficit since 2007-08 and is projected in this year’s budget to remain in the red until at least 2018. This is indicative of significant structural issues with the budget both over the short to medium term, including the period covering the forward estimates, but also well beyond into the future. While many factors have led to the current fiscal position, the underlying problem has largely been driven by low revenue.

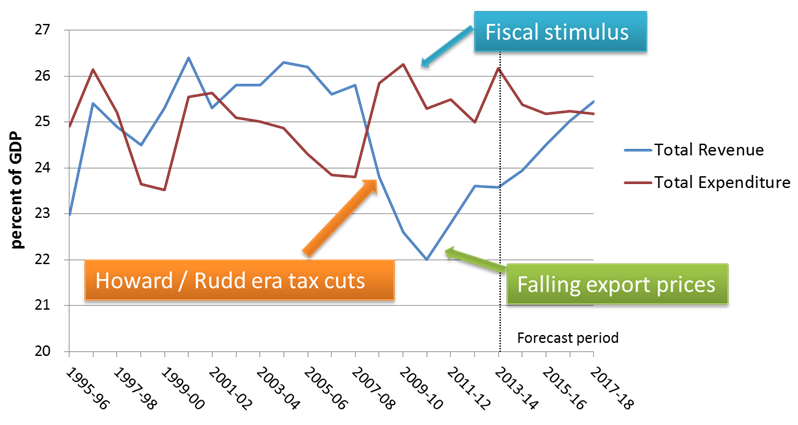

Figure 2: Total revenue and expenditure share of GDP

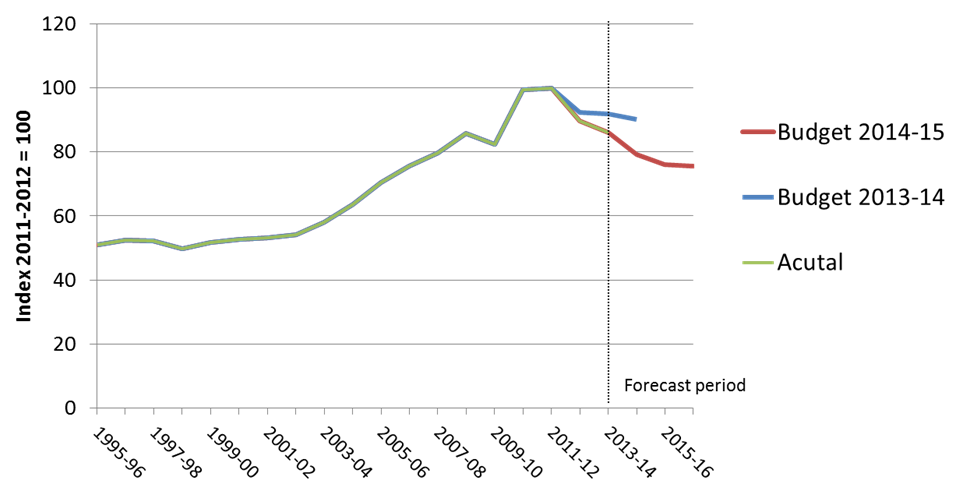

The income tax cuts of the Howard and Rudd era, freezing the indexation of fuel excise, and a declining importance of the GST base have all contributed to low levels of revenue. The GFC also contributed to the budget deficit not through a substantial slowing of the economy but via an overly large and protracted fiscal stimulus spending. Strong Chinese economic growth looked after Australia during the GFC but the end of the resources boom, where Australia’s terms of trade has only fallen since 2011, has contributed to the slow recovery of revenue.

The income tax cuts of the Howard and Rudd era, freezing the indexation of fuel excise, and a declining importance of the GST base have all contributed to low levels of revenue. The GFC also contributed to the budget deficit not through a substantial slowing of the economy but via an overly large and protracted fiscal stimulus spending. Strong Chinese economic growth looked after Australia during the GFC but the end of the resources boom, where Australia’s terms of trade has only fallen since 2011, has contributed to the slow recovery of revenue.

Figure 3: Terms of trade index (2011-12=100)

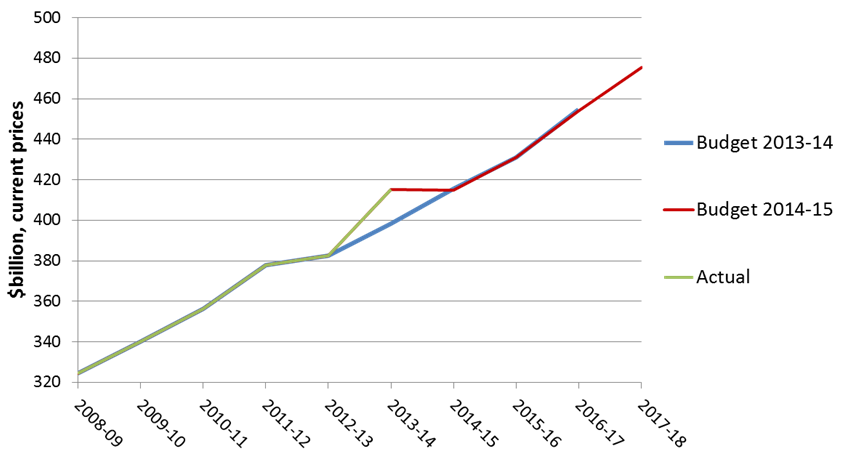

The projected improvements to Australia’s fiscal position reflect some effort to increase revenue (such as through the deficit levy and indexation of fuel excise) but in large part reflect the effect of inflation on income tax receipts through bracket creep. Despite the hard talk by Hockey on cutting spending, total expenditure has essentially remained unchanged relative to last year’s budget. Projected expenditure is really a reprioritisation of government spending with a focus on new infrastructure over social security, education and health spending.

The projected improvements to Australia’s fiscal position reflect some effort to increase revenue (such as through the deficit levy and indexation of fuel excise) but in large part reflect the effect of inflation on income tax receipts through bracket creep. Despite the hard talk by Hockey on cutting spending, total expenditure has essentially remained unchanged relative to last year’s budget. Projected expenditure is really a reprioritisation of government spending with a focus on new infrastructure over social security, education and health spending.

Figure 4: Total expenditure

While revenue has been and will continue to be a problem over the short to medium term, there needs to be serious reform to taxation policy in order to deal with longer term structural issues with the budget. Over the coming decades the fiscal effects of an aging population will hit hard. The rising cost of health provision and the age pension will place substantial strain on Australia’s fiscal position and this will have major implications for the aid budget. Successive Australian governments have cut income taxes in lieu of bracket creep but this may not be affordable or desirable given the demographic change around the corner.

While revenue has been and will continue to be a problem over the short to medium term, there needs to be serious reform to taxation policy in order to deal with longer term structural issues with the budget. Over the coming decades the fiscal effects of an aging population will hit hard. The rising cost of health provision and the age pension will place substantial strain on Australia’s fiscal position and this will have major implications for the aid budget. Successive Australian governments have cut income taxes in lieu of bracket creep but this may not be affordable or desirable given the demographic change around the corner.

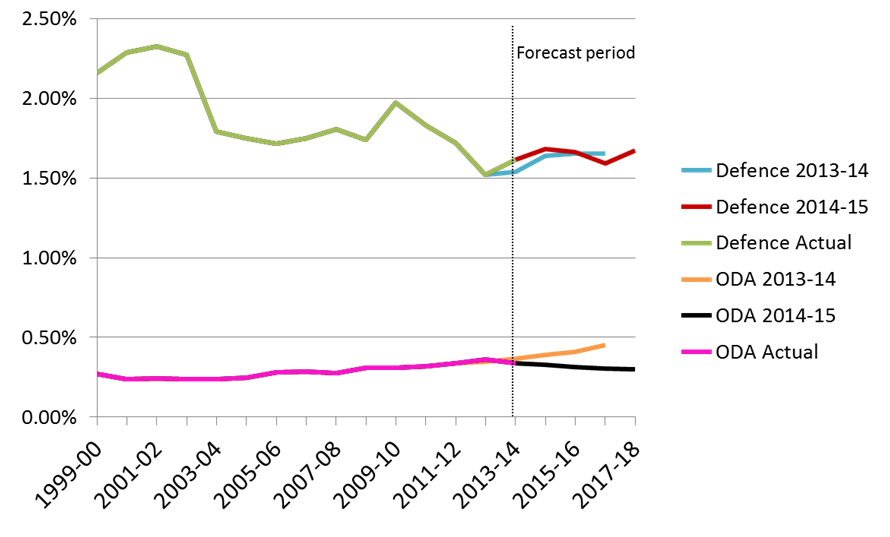

Similar to most other sectors, the aid community will need to lobby hard if it is to achieve increased budget allocations; indeed, it is unlikely that the current government will reaffirm its 0.5% of GNI target for ODA. In contrast, the government has reaffirmed its commitment to increasing spending on defence to 2% of GDP over the next decade. While defence spending has increased in this budget, whether the 2% target is credible remains to be seen.

Figure 5: ODA share of GNI vs. defence share of GDP

In summary, Australia’s fiscal position is difficult and is likely to remain so for quite some time. Under current policy settings, the implication of this is not good for the aid budget, at least in terms of the quantity of aid spending. This is especially the case when cuts to the aid budget have been proportionately higher than elsewhere. Indeed, as Stephen Howes points out, in real terms government expenditure on aid is set to fall by 10% between 2012-13 and 2017-18 despite the Coalition promise in September last year to deliver annual increases in the aid budget in line with inflation. However, government spending on everything else is set to rise by 10% over the same period.

In summary, Australia’s fiscal position is difficult and is likely to remain so for quite some time. Under current policy settings, the implication of this is not good for the aid budget, at least in terms of the quantity of aid spending. This is especially the case when cuts to the aid budget have been proportionately higher than elsewhere. Indeed, as Stephen Howes points out, in real terms government expenditure on aid is set to fall by 10% between 2012-13 and 2017-18 despite the Coalition promise in September last year to deliver annual increases in the aid budget in line with inflation. However, government spending on everything else is set to rise by 10% over the same period.

Anthony Swan is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

Whether Australia actually meets Defence spending of 2% GDP or not the future that is still 50% below the traditional levels of last Century where 3% was the expected norm. The likely cost increases due to fluctuations in exchange rates will probably take up significantly more funds than what is budgeted for future Defence spending.

Foreign aid spending levels are very ephemeral in nature since they have never really been related to realistic long term and sustainable goals. Boomerang aid projects come to mind as well. The point Hockey makes about why we give aid to countries who then give aid to other countries is well made. If we are to try and give 0.5% of our GDP to other nations we need to establish some ground rules about how the money is spent and what bang we get for our buck and whether the end result is what we want?

At the risk of raising the ire of the foreign aid fraternity, current protestations are just that. What is actually required here is a genuine and accountable formula for providing aid that makes a real difference to those we give it to and not just to line the bank accounts of those who are possibly using the money to indirectly stay in power while at the same time absolve themselves of the responsibility to properly govern their country.

Most Australians have no idea about where their foreign aid goes but moan about extra taxes that actually provide the funds for foreign aid. What is required is a more transparent allocation system that provides feedback answers to everyday Australians about what their taxes actually are being used for. The objectiveness of many aid projects in other countries may well not sit well with the Australian people if they were aware of what they are actually funding and how sustainable these projects have been in the past.

A black hole indeed!

Thanks for your comment Paul. About the 2% defence spending target, I know that there are some in the defence community that are in favour of additional spending but would rather not have the target. The rapid increases in spending associated with the target (if they eventuate) can undermine strategic planning and significantly reduce bang for buck. It is interesting that you raise the issue of bang for buck in relation to aid spending but not for defence, especially when the 0.5% target for aid is not on the agenda. I think that the cuts to aid are partly driven by push back from those that think the ramp-up to the 0.5% target was either excessive or not value for money. There is a lot that the defence community can learn from this experience.

On Hockey’s statement, I’d rather save my ammunition for a later blog but I do note that it seems to resonate with a large number of people. I agree with your view about a more transparent and accountable approach to aid but recent changes do not seem to be positive in this regard (for example, see Stephen Howes’ budget blog). DFAT has taken on a big responsibility as managers of the aid program despite never having managed spending of this magnitude. DFAT can value add on a number of fronts in relation to aid effectiveness but transparency, open debate, reduced insularity, rigorous monitoring and evaluation, risk taking, and evidence based approaches need to be further developed in the department.

Tony, This is insightful analysis. It’s clear that aid has become a soft target for politicians looking for cost savings. I wonder what it would take to make it more difficult to cut aid. Protest? Lobbying? The ‘aged lobby’ has been successful in raising pensions in the past; perhaps there are some lessons to be learnt from their efforts? Until there is a more concerted effort to push back against aid cuts, I’m afraid the Australian aid industry will face further downsizing.