The book My Land, My Life: Dispossession at the Frontier of Desire by the Australian National University’s Associate Professor Siobhan McDonnell provides an important new addition to Vanuatu’s land history on the island of Efate, home to the capital Port Vila.

The book My Land, My Life: Dispossession at the Frontier of Desire by the Australian National University’s Associate Professor Siobhan McDonnell provides an important new addition to Vanuatu’s land history on the island of Efate, home to the capital Port Vila.

With a focus on large-scale, speculative land sales, McDonnell traces the land leasing and subdivision journeys of north-western Efate from 2000-2014, and includes detailed case studies of leases, documenting sales and gathering personal narratives of custom landowners about the decisions taken, as well as impacts on the surrounding communities. McDonnell describes how local “masters of modernity” – and they are always male, she notes – facilitated major land subdivisions and sales in collaboration with various Ministers of Lands and private investors, feeding international desire for “a piece of paradise” while simultaneously dispossessing their own families and communities of access to customary land.

The book, published by the University of Hawaii Press, asks how customary land tenure systems and state laws can better interact to facilitate development without alienating people from their customary rights to land. In a substantive contribution to the global scholarship on legal pluralism and collective indigenous resource rights, McDonnell traces the multi-stakeholder efforts of the early 2000s that culminated in the passage of the pioneering and controversial Customary Land Management Act (CLMA) in 2013 under the leadership of then Minister for Lands Ralph Regenvanu. That landmark legislation arrived after more than a decade of extensive consultation led by a wide group of Vanuatu stakeholders – Malvatumauri National Council of Chiefs, Vanuatu Cultural Centre, Ministry of Lands, youth, women and the private sector. McDonnell’s insights as a legal drafter highlight the challenges of designing legislation to engage with pluralistic land tenure arrangements, and the strategies employed to manage land transactions between customary groups, investors and government officials, and between middlemen and their communities. The removal of ministerial powers to overrule customary tenure is a particular legacy of the legislation.

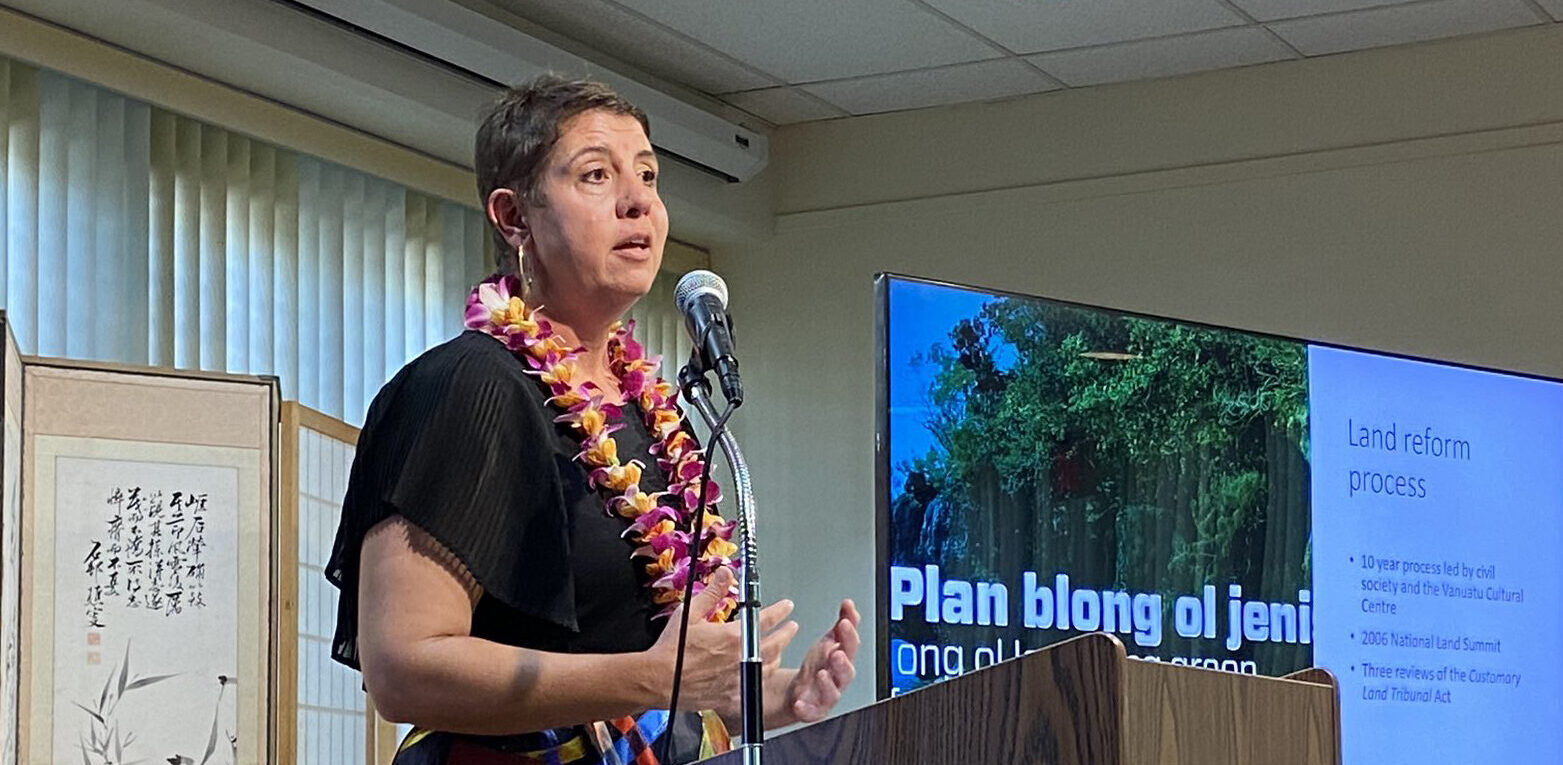

A decade after Vanuatu adopted major land law reforms, at the ANU Crawford School of Public Policy launch of My Land, My Life in Canberra on 10 October, Ralph Regenvanu, now Vanuatu’s Special Envoy on Climate Change, noted that while the intense land speculation of the early 2000s had abated under the new legislation, “there is still some way to go in strengthening land administration processes to fully deliver on the intent of the law.” Indeed, in late 2023, the National Customary Land Management Office came under intense public scrutiny following allegations of corruption and numerous appeals alleging manipulation of customary land systems.

The future of Vanuatu land policy and management is also tied up with how our country faces the challenges of climate change. The tensions between modern (often international) legal frameworks and customary land management systems will again be in the spotlight, not only in relation to climate adaptation and relocation planning, but also as the Vanuatu Government pursues carbon credit initiatives.

While carbon credits offer potential environmental and economic benefits, there are significant challenges to address before implementation. To be effective, beyond the requisite policies, laws and safeguarding regulations, green carbon credits require ready access to Vanuatu’s customary land. With 97% of land in Vanuatu under customary tenure (notwithstanding a significant amount under lease), the engagement of customary landholding groups in any land transaction is essential and legally mandated by the CLMA. While Vanuatu is still in the process of establishing how carbon credits will be managed, traded and monitored, the government will also need to consider how approvals for schemes are granted, how benefits are distributed and the balance of power between customary land groups and state authorities. Without giving appropriate attention to these foundational issues, the government risks exacerbating land conflicts and marginalising its customary landholders, undermining the potential benefits of carbon credit initiatives.

My Land, My Life is a cautionary tale of why it is important that land dealings respect the rights and requirements of customary groups. While the rich accounts contained in the book are unique to Efate, the portrayal of “masters of modernity”, investors and government officials could also describe their behaviour on other islands in the archipelago. This concept reflects not only the desires of foreign investors, but increasingly also the desires of Vanuatu’s home-grown investors (including politicians and local businessmen), which highlights the urgency of getting land administration right within the law to protect customary rights and promote genuine investment and public goods. This urgency is even more apparent as Vanuatu considers a new carbon credit regime which will require access to considerable tracts of customary land and forest.