In the past few weeks the Devpolicy blog has been highlighting the sobering trend of recent declines in foreign aid spending, both on a global scale and domestically with the case of Canada. Australia is one exception to this trend (see relevant budget posts here); the UK is another. But how is the UK progressing in its effort to scale up aid while in recession?

UK aid to date

Net ODA/GNI ratios (expressed as percentages), UK & OECD DAC average

Source: House of Commons library briefing available here [pdf].

As can be seen in the chart above, up to 2000, UK aid as a ratio to national output (GNI) was similar to the DAC average. From 2000, however, the UK began a major scaling up of its aid program, reflecting its 2000 commitment to the Millennium Development Goals. Apart from a dramatic fall in 2007, due to high levels of debt relief in 2005 and 2006, aid has consistently risen since 2000 both as a ratio of GDP and in absolute terms.

The UK should also be credited for the ‘International Development Act’, which was passed into law in 2002, that enshrines poverty reduction as the core focus of DFID’s work, and effectively outlaws tied aid. The UK is also one of the few countries in the world that retains a cabinet minister for international development, a recommendation the Australian Aid Review (p. 28) discussed but ultimately dismissed.

The march towards 0.7

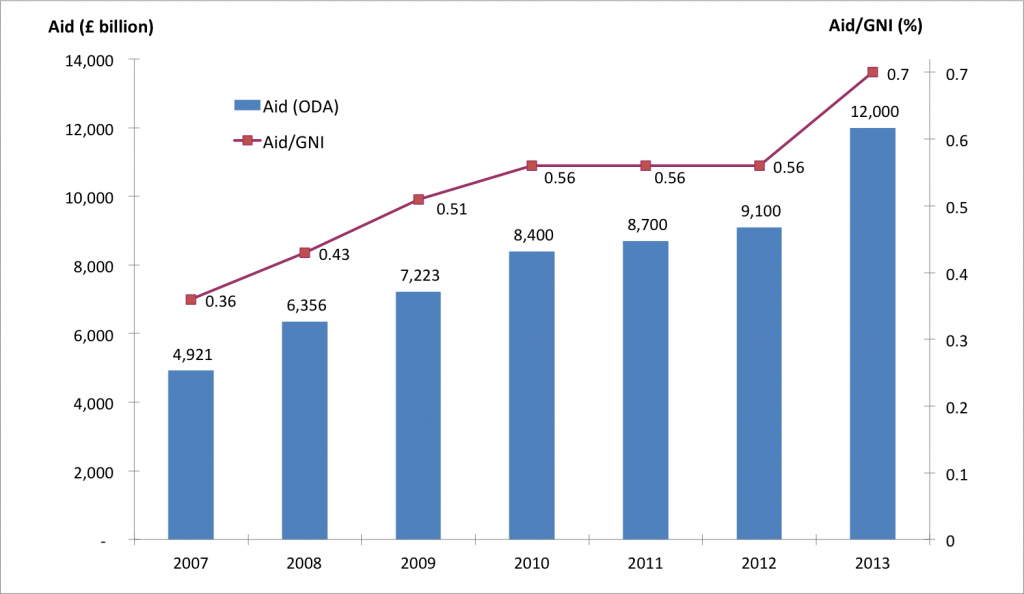

The Blair Government set a clear timetable for increasing ODA to 0.7% of GNI by 2013 as a part of their 2005 General Election platform. The Coalition Government, which came to power in 2010 promising, and implementing, severe austerity, has so far quarantined the scaling up of the aid budget. The last three budgets have held ODA/GNI steady at 0.56%. The Coalition Government has also constantly reaffirmed the multi-party commitment to reach its 0.7% ODA/GNI target by 2013.

The big challenge lies ahead

While quarantining the aid budget from austerity is in itself an impressive achievement, the big challenge for UK aid is clearly still to come.

The scale-up to come

Sources: Figures to 2010 from DFID’s 2011 Annual Report here [pdf], p. 111. Figures from 2010 onwards taken from the 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review here [pdf], p. 60. Updated forward estimates, but recorded in financial year (April-March) terms found in the 2011 Annual report here [pdf], p. 10, also verify this trajectory. Note that although the UK budgets April-March it also produces calendar year estimates of ODA as this is how all donors report to the OECD.

As can be seen above the Coalition Government has a monumental task ahead of it when it brings down next year’s federal budget. The trajectory of the scale-up, as outlined in the 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR), has left the heavy lifting for the final year. The CSR document shows that ODA in next year’s budget will rise by an astounding 32%, or around £3 billion, to match the Government’s commitment.

Besides the obvious concern of the political feasibility of such a large increase, how DFID will be able to effectively spend that amount, and sustain that spending beyond 2013, is another big question. The difficulty of answering these questions may be cause enough to delay or postpone next years scale-up, and recent events have drawn concern from campaigners across the UK that the 0.7 target may be in jeopardy.

The failure to legislate 0.7

The Coalition Agreement between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats included an agreement to legislate the 0.7 target. However, the Queen’s recent speech to Parliament, which outlines the legislative agenda for 2012-13, included no reference to this. Also, a recent House of Lords’ inquiry into aid advised against a 0.7 bill.

Postponement of the 0.7 bill has been hinted at for months, with the official line being that there is simply not enough time in the legislative agenda as the Government continues to focus on the economy. The Bill, however, is ready for submission and supported by all three major parties so would take up little time.

This failure to legislate, combined with the major surge required in next year’s ODA budget to reach the 0.7 target, is due cause for concern. With the majority of the painful austerity cuts still to happen a backdown, or at least a postponement in relation to the 0.7% target, would not come as a surprise. After all, this is just what Australia has done.

But it is important to put this uncertainty in context. Unlike Australia, since 2010 the UK has planned on managing their scale-up with this final year spike, with forward estimates consistently incorporating the surge in consecutive budgets. There is also still a clear bipartisan commitment (by the Coalition Government, grumblings of dissent in the backbench aside, and Labour) despite polling suggesting public opposition. This is in itself quite remarkable given the UK’s difficult economic and fiscal position.

The bottom line: expect further increases in aid in the UK, but don’t hold your breath for 0.7 next year – unless UK’s politicians hold their commitments to the world’s poor to a higher standard than our own.

This blog is part of a series on 2012 Aid Budgets. For other blogs in the series, see here.

Jonathan Pryke is a Researcher at the Development Policy Centre.