Aid programs are increasingly called on to be flexible, adaptive and to ‘think and work politically.’ In DFAT, barely a program is approved without this terminology being peppered through the design document. But what do these ideas mean in practice? How can implementers, tasked with bringing designs to life, deliver on their promise meaningfully? And how do donors need to manage adaptive programs differently to conventional ones?

In a series of three blogs over the coming weeks, the Institute for Human Security and Social Change will set out some ideas about what it take to program adaptively. These are drawn from our experience of working alongside primarily DFAT and DFID funded programs in the Pacific, Africa and Southeast Asia that have sought to integrate adaptive ways of working. Most recently, this includes working with the PNG-Australia Governance Partnership and the Solomon Islands Resource Facility, but also extends to domestic work with organisations like the Central and Northern Land Councils.

Each blog will deal with a different component of the challenge – first adaptive implementation; then adaptive monitoring and evaluation; and finally the role of research and learning.

A lot has been written already on what examples of adaptive programming look like (see here, here and here, for instance). In requires hiring the right staff, putting in place regular sessions to reflect and redesign, increased risk appetites, and so on. But when the rubber hits the road, programs that seek to be adaptive run into several areas of confusion, which we try to clarify here.

- Adapt theories of change, not (just) activities

There is often confusion about the level at which adaptation is to occur. Often, programs point to changes in their activities as demonstrating adaptation. For instance, participant feedback indicates that some aspect of a training was not well understood and so the program adapts the curriculum. This is good practice but is really just problem solving. Hopefully programs were doing this anyway!

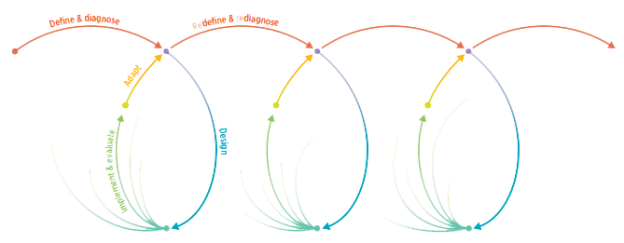

Adaptation is not about tweaking activities but about instilling a learning approach at the heart of programming. This means being open to the idea that your entire theory of change might need to adapt, not just the activities being rolled out in support of it (this is also referred to as double loop learning). Rather than focusing on activities, adaptive programming focuses on understanding how change happens, and adapting theories of change to reflect learning about this. An adaptive program is one that can shift from supporting one approach to change, to another. What changes is not simply program activities, but the underlying logic of how to make change happen.

- Don’t rely on results alone to trigger adaptation

This raises the question of how you know when to adapt and when to stay the course. There are dangers of constantly changing course and not sticking with strategies for long enough to see results. However, most programs tend to be reticent to change existing strategies because of sunk costs and risk aversion, among other things. A key problem is that programs rely on results as the trigger for adaptation. Intuitively, this makes sense, given that adaptive programming came about to deliver better results from aid spending. The problem is that results can be slow to emerge. If we wait for an evaluation to tell us whether strategies are working, adaptation will happen very slowly.

What is needed is a series of other, softer markers of progress along the way that can help determine if we’re on the right path. For instance, have we been able to secure meetings with the necessary counterparts to get traction? Where social media is an important political forum, are the coalitions we support building a following or gaining profile? These kinds of markers are not enough to determine success or otherwise, but they can help programs make decisions about whether the weight of evidence is on the side of staying the course, or changing strategy.

Other prompts for adaptation can be the team’s evolving knowledge (of people/groups and their interests, incentives and power), emerging opportunities or roadblocks. To be adaptive, programs need to find ways of routinely capturing these kinds of triggers for change.

- Make sure your staffing and workplace culture are fit for purpose

The reliance on the team’s evolving knowledge and networks has implications for staffing and program culture. While programs usually hire staff for their technical skills and experience in meeting the donor demands, adaptive programming calls for valuing other skills and attributes. You need staff with political nous, local knowledge, networks and connections. The technical is not unimportant but is also not sufficient. Adaptive programs recognise that the key constraint to developmental change is rarely a lack of technical knowledge or capacity but the constellation of political incentives. You need staff, then, who can navigate this.

What’s more, you need a work environment in which those staff are routinely encouraged to critically reflect, question and speak up. This can be institutionalised in moments of reflection and redesign (be they strategy testing, reflection and refocus, etc.) but should also be reflected in the wider organisational culture. Otherwise reflection sessions will fall flat, or only capture dominant voices. Your staff – particularly local staff – need to know that they, their knowledge and networks, are valued and relevant in navigating the path to change. They are not simply there to deliver on implementation plans. This can be done through management practices, but also through HR policies – do pay, conditions, security policies and the like demonstrate that local and international staff are equally valued in their contribution to supporting change?

- Donors: let go of the reigns but stay engaged

Adaptive programming does not only require implementers to change their ways of working. Donors, equally, need to recognise that adaptive programs require different management to conventional programs. Implementing partners – be they NGOs or private contractors – are just that: partners. They are on your team. You are navigating the path to developmental change together. As a result, they require a reasonable degree of trust and room for manoeuvre. If the political economy within your own donor organisation militates against this, then you need to think and work politically within your own organisation. As much as possible, slow the pressures coming from your own political economy to create space for change in the country you’re working in. Change happens in that environment – not through cables or reporting to donor headquarters.

None of this means donor staff need to be disengaged. Donor staff possess important information, ideas and relationships that can be brought to bear on development programming. In an ideal world, the donor-implementer relationship would be such that donor staff would participate in reflection and redesign sessions – not for accountability purposes, but to contribute to the melding of minds required to figure out how to support change.

- Be realistic about the tools you have available

Donors and implementers need to be realistic about the scope of adaptation that is possible given the tools available (there are also a whole host of political realities that play a constraining role that we won’t get into here). If your program is a technical assistance facility, for instance, you face the challenge of having already decided on the tool before you know what the problem is that needs to be fixed. This means the room to adapt is restricted – you likely can’t all of a sudden become a community grants program, for instance. But you can still be creative within the space available. While technical assistance, in its worst forms, substitutes rather than builds capacity, there are a range of potential roles that technical assistants can play in different contexts – from advising, to convening, to building coalitions, to joining the dots between different reforms.

Similarly, if you are operating a community grants facility, you can encourage adaptive ways of working amongst local partners, and/or use grants strategically to support multiple approaches to change, investing in learning about what works and why. Working adaptively will therefore look different and face different constraints depending on the nature of the program. Being upfront and realistic about the scope of adaptation that is possible will moderate expectations, and help others understand what adaptiveness means in practice for your program.

This is the first in a three-part series on adaptive aid programming. Part two will look at adaptive monitoring and evaluation, and part three at the role of research and learning. A pdf of all three posts can be found here.

A useful piece Lisa, and looking forward to the next two. On MEL you might want to take a look at our recent summary of a discussion on a related topic: https://asiafoundation.org/2018/09/12/monitoring-evaluation-and-learning-in-adaptive-programming-expanding-the-state-of-the-art/

or at this blog summary from Arnaldo Pellini: https://arnaldopellini.org/2018/06/21/mle-or-mel-in-adaptive-programming/

or Chris Roche’s take: https://oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/simplicity-accountability-and-relationships-three-ways-to-ensure-mel-supports-adaptive-management/

thanks, Sam

Hi Lisa, great piece and looking forward to reading the other two articles.

I agree that aid programs are moving from conventional programming to adaptive programming, and also captures political economy analysis (PEA) or thinking and working politically. I work in this space in PNG for a while now and can attest this change.

The theory of change that follows conventional programming approach centres on ‘planning from the outside’ for a client, and in nearly all cases does not involve the client(s). If it does, it reflects those who are not immediately affected. It involves very little PEA, and also very little of Thinking and Working Politically. I believe that is where the problem lies and the issues of sustainability, capacity building and all else with reforms.

The planning for adaptive programming approach takes the best of both worlds- conventional and adaptive. The Theory of change for an adaptive approach considers the ‘context’, and within that ‘context’ are ‘local solutions to address local problems’ with involvement of local actors, driving the change. This is something pertinent to PNG, and I am sure others as well. The adaptive programming approach, with involvement of PEA and inclusion of thinking and working politically, I am sure will make a difference in how donors work, and especially in PNG.

I hope your other articles capture aspects of the above.

Many thanks for your comments John – yes indeed, adaptive programming fundamentally requires a ‘thinking and working politically’ approach, informed by good political economy analysis. I’m not sure that all programs that claim to be adaptive live up to that in practice (would welcome your thoughts on that in the PNG experience!) but certainly that’s the intention…

Hi Lisa, I agree. Not all programs claiming to be adaptive are using TWP and PEA analysis. Those who are using those tools are doing so at various degrees and levels. My experience shows that those who are using those tools more often are driven by the need to understand the ‘local context’, and I also believe that those programs are in the front this work in PNG.

Hi Lisa, Thanks for this piece, and we are looking forward to the next two as well.

I did want to comment on your remarks on technical assistance, and the claim that the worst form of TA is one of capacity substitution. My experience is the opposite. The use of “advisors” to pursue the old holy grail of “building capacity” more often fails than succeeds. Much better that the expensive experts actually do something useful – especially in fragile states when they are typically “substituting” for non-existent capacity (and when they often have no-one interested in their advice).

I’ve written about this quite a lot in the PNG context, and I’d invite anyone interested in the subject to read my blog: https://devpolicy.org/shifting-in-line-in-png-20150806/.

Relatedly, I do think there is a danger that we put too much under the adaptive rubric. Whether it is better to hire people to provide or build capacity has nothing to do with whether a particular program is designed adaptively.

Regards,

Stephen

Thanks Stephen – my TA line was a bit of a throw away and not well explained. I agree that there are instances where substituting capacity may be necessary (and where the importance of getting a task done immediately outweigh that of longer term capacity building). But the Australian aid program remains quite TA heavy and I think there is also a danger that TA are too often the default answer. My wider point, however, is that even if you are in a program with lots of TA (which may constrain your ability to adapt to some degree) there are a variety of roles that TA can play that you can adapt the program to as is appropriate.

The issue of whether there is too much TA in the Australian aid program (surely, yes) is quite different from whether enough of that TA is spent on actually doing useful things (surely, no). The problem with suggesting that there are other “fancy” things TA can do (like “joining the dots” as you suggest) or of giving approaches to TA labels such as adaptive is that this simply legitimizes further reliance on TA with little or no return. It becomes a form of whitewashing.

Yes, that may well be true Stephen! My argument is about trying to make the most of what we’ve got (trying to get TA to work better, given there’s so much of it), but you are right that this approach does run the risk of continuing to legitimise its use in the longer term.

Thanks Lisa for this nice piece.

Aid programs need to follow conventional methods of flexibility, adaptability and working politically to appease both the donor and recipient countries so that both are on a winning curve. The Australian Aid program to the Pacific and elsewhere followed this method of aid program. The implementing parties and the recipient governments are guided in this principal to make good use of aid funding or other form of assistance.

However, two important factors that you have not discussed here are sustainability and managing risks. Aid is external support with a fixed timeframe, the aftermath of the aid program is all about sustaining the program itself or integrating it into existing country’s program – sustainability. How the direct and associated risks which emerge as a result of aid programs is managed, is another key question. Without sustainability and a risk management plan, one would hardly anticipate adaptability of aid program in a country’s development or strategy.

Currently in PNG and Pacific countries, Australian aid program emphasis more on sustainability and risk management of aid program than adaptability.