Does emphasising the benefits aid brings to Australia make Australians more positively disposed to giving it? Some politicians clearly think it does. On the other hand, groups like the Campaign for Australian Aid take a different approach. They advocate for aid on ethical grounds alone, ignoring what’s in it for us.

Both types of appeal are plausible. No one’s ever studied what actually works though. Earlier survey work has shown most Australians want government aid focused on helping people overseas. This is suggestive. But people’s preferences about how existing aid should be spent aren’t the same thing as the type of information that might actually change whether they support more aid or not.

Late last year we conducted a survey experiment to shed light on what types of appeal, if any, increase support for government aid. All of our findings are described in full in our new Devpolicy discussion paper.

The experiment involved a sample of over 4,000 Australians. Each participant was randomly allocated either to a control group who were only asked a set of questions about their views on Australian aid, or to one of several treatment groups.

Each of the treatment groups was provided with a short newspaper-like article about an Australian aid initiative – an initiative modelled on the Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security. (We didn’t use the Centre’s name, so as to avoid any connotations associated with the word ‘security’.)

One treatment group – which we called the ‘basic treatment group’ – were just provided with some very simple information on the aid initiative, and a broad endorsement from an academic. Another group – the ‘national interest group’ – was provided similar information and a similar endorsement but written in a way that emphasised how the initiative would benefit Australia by preventing epidemics from spreading here. A third group – the ‘altruism group’ – were told how the initiative would help people in developing countries. A final treatment group – the ‘global leader group’ – was given an article designed to appeal to Australians’ national pride by telling them how the initiative made Australia a global leader. (The exact wording of the treatments is in the discussion paper.)

Treatment allocation

Immediately after they’d read the newspaper article, participants in all of the treatment groups were asked the same questions about Australian aid that the control group had been asked. These included a question about whether they approved of Australia giving aid, and a question about whether they thought Australia gave too much or too little aid. Because assignment to the different groups was random, comparing responses between the groups captures the effects of describing the aid initiative in different ways on people’s views about aid.

Our full findings are in the discussion paper. But, most importantly, we found:

All of the treatments, including the basic treatment, increased general approval of aid giving (by roughly ten percentage points) and decreased the percentage of the population who thought Australia gave too much aid by a similar extent. Simply providing people with some tangible detail about what aid is doing, and coupling this with endorsement from an independent expert, is enough to have a substantial impact on support for aid. The specific way aid is framed – basic information, appeals to national interest, altruism, etc. – doesn’t seem to matter much for these improvements.

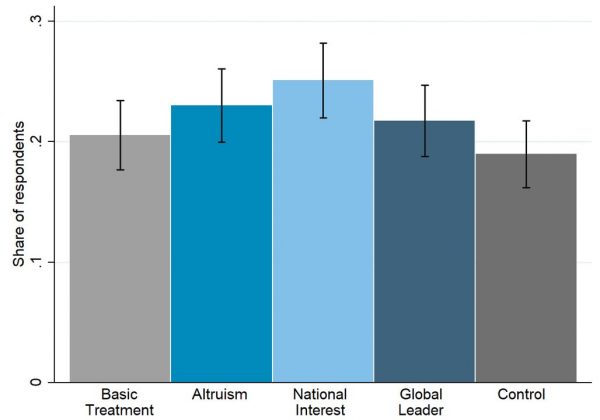

Increasing the share of Australians who thought Australia gives too little aid was more difficult though. Only the altruism and national interest treatments brought statistically significant increases, and the increases were only in the vicinity of about five percentage points. You can see this in the chart below.

Share of respondents who think Australia gives too little aid

You can also see that the national interest treatment appears to have had the largest effect. The difference in effect size between the national interest and altruism groups isn’t statistically significant though, so we can’t say that appealing to national interest is definitely the most effective. However, national interest not only appears to have a larger effect than the altruism treatment, it’s also the only treatment that has an effect that is statistically significantly larger than the basic treatment. Together these results suggest that emphasising national interest is likely the most reliable means of using an initiative like the Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security to boost support amongst the public for a larger aid budget.

That’s not the end of the story though. Participants were often cynical about the motives of the aid initiative described in the articles they were given. Regardless of the treatment, a significant share of participants in all of the treatment groups thought the project was designed primarily to help Australia. (For example, 45% of participants who received the altruism treatment still said they thought the initiative was designed to help Australia.)

When we limited our analysis to participants who believed the initiative was motivated by the purpose emphasised in the treatment they received, the altruism treatment actually performed the best. For these participants, its effect in increasing the percentage of Australians who thought Australia gave too little aid was at least as good, and possibly better, than the national interest treatment, and it outperformed all the other treatments in reducing the share of the population who thought Australia gave too much aid.

There’s still more to be learnt. For example, it’s possible that other types of aid projects might have different effects on support. For now though, our findings show that emphasising particular rationales for aid giving can change support for aid. They also suggest that appealing to the national interest is an effective means of boosting support. Appealing to people’s altruistic tendencies may be more effective still – but only if the public can be convinced that aid is really being given for the sake of helping others.

Read the full discussion paper here.

Aid is many things, but it is largely portrayed/seen as a charity, in a rudimentary manner. This portrayal is one-sided, self-serving, reductive. Perhaps a fuller and fairer description of aid is ‘benevolent self-interest’. As a form of helping hand, aid is an investment in people and countries, with the benefits of good aid projects also accruing to the investor in many forms, including economic, diplomatic, etc. If the benefits are not seen/felt in the short term, then certainly in the long term. Most people understand investment in the cold, hard, conventional, neo-liberal sense. Perhaps if Aid is explained, portrayed and sold as investment, there will be a greater level of public understanding/acceptance. Research on the return on investment should be prioritised and it should also be publicised. Reports on aid projects show spectacular failures, yes, but also some stellar successes.