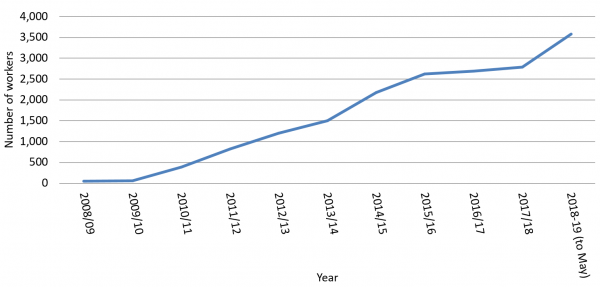

Pacific observers often ask why Tonga has been so successful in the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP), despite the country’s small population (105,000), and its remoteness requiring costly travel to Australia. Since the inception of the SWP in 2008, tiny Tonga has supplied almost half the scheme’s workers (46 per cent to be precise). Although Vanuatu now sends one-third more workers to Australia than Tonga, it has a much larger population (almost three times the size). And, as you can see from the graph below, Tongan SWP numbers are growing again, after a slow couple of years.

Tongan SWP workers

Source: Department of Home Affairs

An important part of this success is the role of Tongan intermediaries. These range from labour hire firms run by Tongans resident in Australia, to intermediaries based in Tonga, and to return workers who act as informal recruitment agents.

Tongans resident in Australia own and manage the two largest firms engaging Tongan workers. They accounted for nearly two in five of all SWP workers from Tonga in 2018. Both these top two approved employers are labour hire firms. Another major labour hire firm, accounting for nearly one in ten SWP workers from Tonga, has a close working relationship with two Tongan-Australian growers who do their own selection of workers. These three approved employers with close Tongan connections account for near to half of the Tongans employed on the SWP in 2018. They actively promote Tongan workers to Australian growers.

The labour hire operators and growers have formed close working relationships with agents, known officially as ‘third parties’ in Tonga. At least one Tongan agent, who is an Australian resident, moves between the two countries, and is a recruiter for one labour hire company. This intermediary also provides pastoral care services for up to four small and medium-sized growers who are approved employers. In total, about three in five workers in 2018 were employed through a close Tongan connection.

Return workers are the other intermediaries who play a key part in growers’ continuing preference for workers from Tonga. Australian visa statistics show that from 2013-14 to end April 2019, two thirds (66 per cent) of SWP visas granted to Tongans were to return workers. Return workers are not only highly desirable because they self-select to come back. In addition, the employer chooses to invite back only those who have shown themselves to be more productive. Employers also use return workers as informal agents, asking group leaders or other return workers to select other workers they can vouch for.

Help from the diaspora, while important for Tonga, is not essential for SWP success. This can be seen from the example of Vanuatu which, as mentioned, has now overtaken Tonga as the biggest supplier of SWP labour, even though Vanuatu has a much weaker diaspora in Australia.

A deeper factor underlying the SWP success of both Vanuatu and Tonga has been these countries’ private-sector oriented approach to the scheme. Both countries have allowed employers to recruit workers directly, including through agents, without interference from government. Neither country relies on a government-selected work-ready pool to recruit workers. Vanuatu doesn’t have a work-ready pool at all, and in Tonga employers are not required to use it. The liberal approach taken by the two countries has allowed Tonga to exploit its diaspora advantages, and Vanuatu to leverage its early experience in the New Zealand seasonal work program to grow rapidly in Australia.

The diaspora has not been an unmixed blessing for Tonga. It is reported that, for the period December 2017 to August 2018, about 100 Tongan workers absconded from their employer, or about 5 per cent of all SWP visas for Tonga approved over this period. The main factor appears to be the entreaties of relatives resident in Australia.

Employer worries about absconding workers may have contributed to the slow growth in the number of Tongans recruited between 2015-16 and 2017-18. However, Tonga has taken remedial action. These include stopping absconders and their families from accessing both the Australian and New Zealand seasonal work programs, a greater emphasis on community selection of new workers, and placing a liaison officer in Australia.

For the current financial year, based on the first 11 months, the number of workers from Tonga has reached 3,600. This suggests that the corrective actions by Tonga may have helped, and that it is once again on a growth pathway.

Tonga’s experience speaks to the advantages (and also some of the problems) of the diaspora when it comes to success in the SWP. More fundamentally, what Tonga demonstrates is that success in the SWP requires facilitation but not control. Governments should definitely allow employers to recruit workers directly, including via agents. But the experience of Tonga also shows that governments have an important role to play in providing safeguards, monitoring compliance and stepping in when things go wrong. With success, the role of government in the SWP actually becomes more not less important. This is the challenge that Tonga is currently facing.

Leave a Comment