This post explores the implications of the August Economic Statement [pdf] for Australian aid, and for aid to PNG. The use of aid to fund the PNG resettlement solution – the part of the statement which in fact raises the most questions – is explored in this companion post. Some graphs highlighting the latest aid budget developments are provided at the end of the article.

Pushing back the scale up

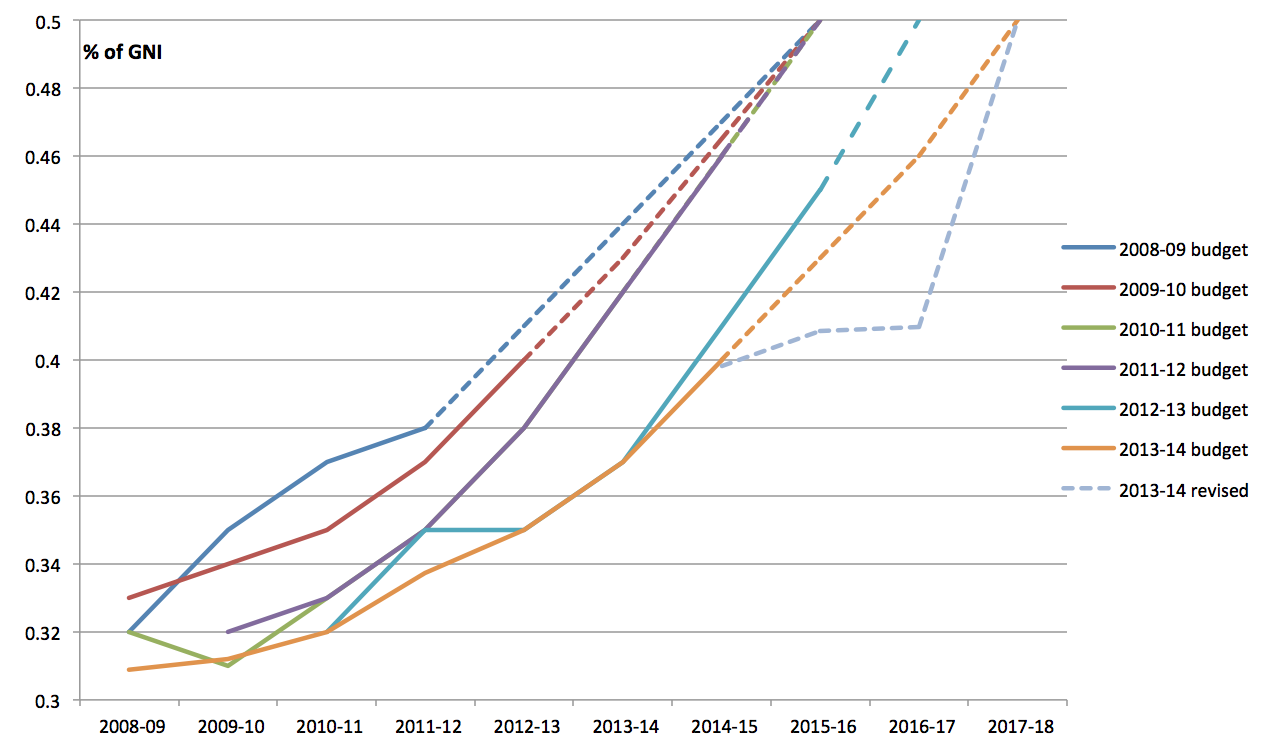

Once again, the Government has pushed back its promised scale up of aid to 0.5% of GNI. This is the fifth time it has done this since the 0.5% target was first promised, for 2015-16, five years ago in the 2008 budget. It has delayed the target date twice (in the 2012 budget to 2016-17 and in the 2013 budget to 2017-18) and changed the trajectory (increasingly back-end-loading it) without changing the target date three times (in 2009, 2010 and now in this August Statement).

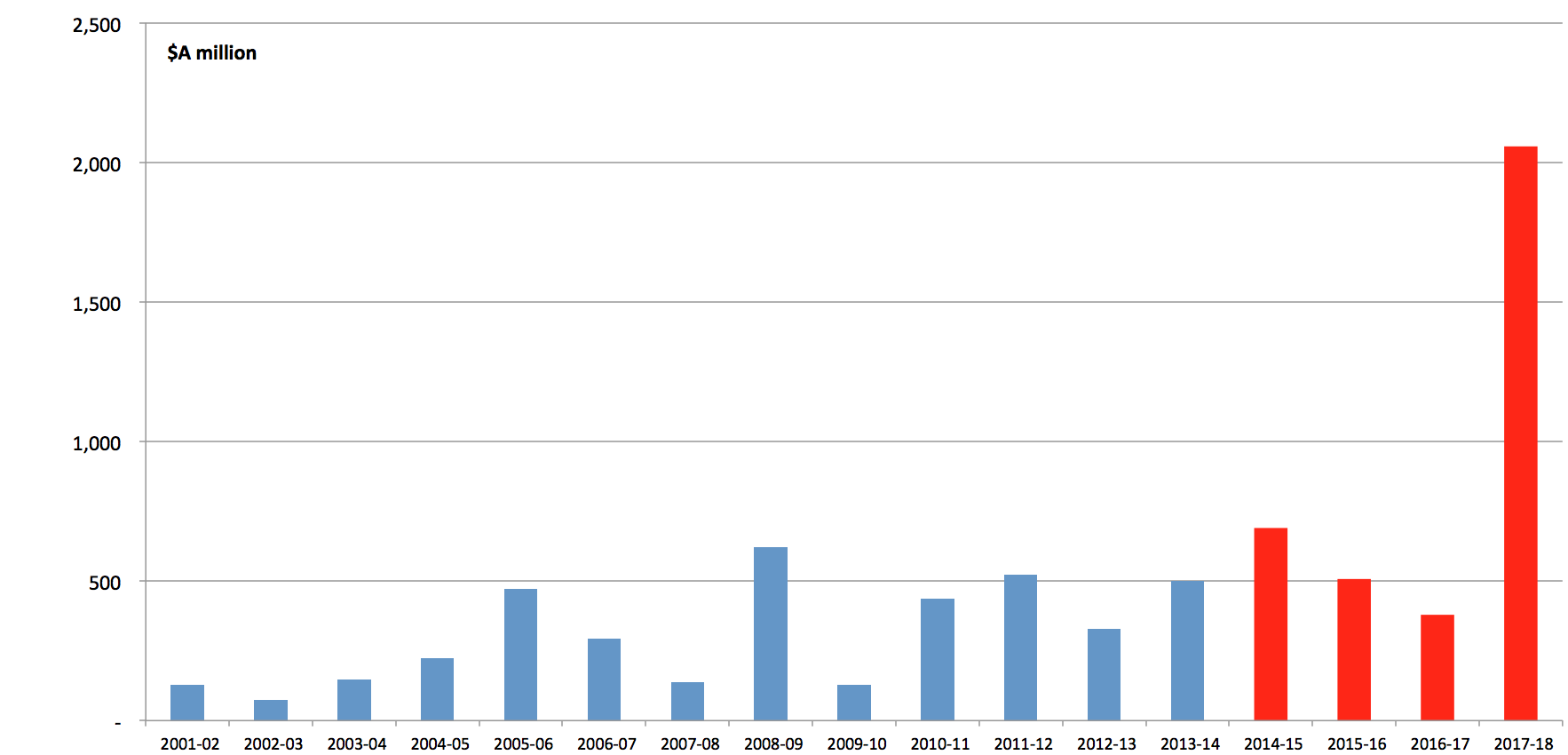

To get to 0.5% of GNI, aid will now need to be increased by $2 billion in 2017-18 (the first year outside the forward estimates, and so not subject to the current budgetary pressure). The largest aid increase ever in Australia is $620 million (2008-09). The average under Labor is $425 million. A single-year increase of $2 billion is not impossible. The UK increased its aid by £2.5 billion this year to get from 0.56 to 0.7% of GNI. But against a backdrop of repeated postponements, it is fanciful to think the Australian aid budget will be increased by $2 billion in 2017-18.

The increases promised over the forward estimates are still impressive. In my analysis [pdf] following this year’s budget in May, I suggested that the 0.5% target was no longer credible, and that both sides of politics should coalesce around a more doable target, such as a $500 million increase in aid every year. Interestingly, that is what the Government is now promising us for the next three years with increases of $670 million, $510 million and $380 million respectively, an average of $520 million per year. This gets us to 0.4% of GNI next year, and then keeps us there.

Is 0.4 the new 0.5?

Aid to PNG: expensive police, and other interesting details

PNG features prominently in the August Statement. It is promised $420 million more in aid over 4 years, an increase of about 20% over the current annual aid allocation of $500 million (plus any aid-eligible resettlement costs, on which see the companion post). PNG’s budget was set to increase in any case. This increase insulates it against a smaller or slower overall aid expansion, but should be seen in the perspective of a growing aid budget. Over the next three years, PNG is set to get about 20% of the overall aid increase. Another way to put the increase into perspective is to recognize that Australian aid to PNG has already increased by $100 million over the last five years.

Some interesting detail is released in the statement’s Box 3 about various PNG aid initiatives:

- The deployment of the 50 police to PNG is costed at $132 million over four years, which works out at $660,000 per police officer per year. The AFP refused to participate in a cross-departmental exercise a couple of years ago to rationalize the costs of Australian government advisers working on the aid program. $660,000 per officer seems expensive, especially when you consider that AFP police serving as long-term advisers will receive tax-free salaries in PNG. The statement also clarifies that these police will only be engaged in “advisory and mentoring roles in local police stations.” This is because, unlike the police who arrived in PNG in 2004 (under the ECP), they won’t have diplomatic immunity. But it also means they probably won’t be very effective in improving law and order. They certainly won’t be “visible,” as claimed by Rudd, if they don’t leave the police station.

- For the three capital projects, which are at the heart of the new aid deal (and a departure from traditional Australian aid practice, as argued here), construction is only committed to in the case of the Lae hospital. Only scoping studies are promised for the Madang-Ramu highway and the Moresby courthouse. Presumably, construction costs for these projects will follow. The price-tag for the resettlement deal may far exceed the amount announced so far.

- For the first time, the commitment to fund universities is made concrete with an undertaking to spend $62 million on the rehabilitation of the University of Papua New Guinea. UPNG is an important national institution in PNG, and has a reforming Vice-Chancellor. It is good to see it receiving support, though ironically, the day of the August Statement release (Friday 2 August) also saw protests by UPNG students against the asylum-seeker deal. Apparently students are boycotting classes, and more protests are planned for next week.

Some aid graphs

This graph shows aid/GNI ratio in successive budgets since 2008-09, which was the first budget to implement an expansion towards a 0.5% target. Solid lines are historical and budget years; dashed lines are forward estimates and, if required, projections beyond the forward estimates period to get to the 0.5% target. Revisions over time of the historical numbers and back-end-loading and postponement of the 0.5% target have both led to current and projected aid being much lower than earlier projected.

This graph shows aid increases (in current prices) since 2001-02. The blue lines are historical and this year’s budget figure. The red lines are calculated from the August statement.

Note: These figures combine 2013-14 and earlier budget aid/GNI figures, the revisions provided to aid forward estimates in the August Statement, and the August Statement’s nominal GDP growth figures.

Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre.

Correction: Garth Luke has pointed out to me an error in these calculations. In fact, the estimate for the aid increase in 2016-17 should be $547 million (not $380 million), giving an average increase for the three years in the forward estimates of $577 million (not $520 million), and leaving a required increase of $1.9 billion in the final year (not $2.1 billion). Thanks Garth.