As I stared glumly at Australia and New Zealand’s lowly rankings in the 2016 OECD aid generosity tables, I started searching for an explanation. Or, to be more precise, an excuse. Neither Australians nor New Zealanders seem like tight-fisted people, so perhaps there was a good explanation as to why our countries languished at 17th and 19th out of 30 donors in the OECD’s donor club at the end of 2016.

Maybe, I thought, it was because we’re poorer than the average donor. Obviously, neither Australia nor New Zealand is actually poor. But we are poorer than countries like Norway and Luxembourg, which give a lot of aid. And it seems reasonable enough that poorer donors give a lower share of their Gross National Income (GNI) as aid. After all, running a country and taking care of its people involves fixed costs that aren’t any lower for less-wealthy nation-states. You often hear opponents of aid saying that we need to take care of our own first. Perhaps that was the explanation: that we’re simply not rich enough to be as kind as most other OECD countries are.

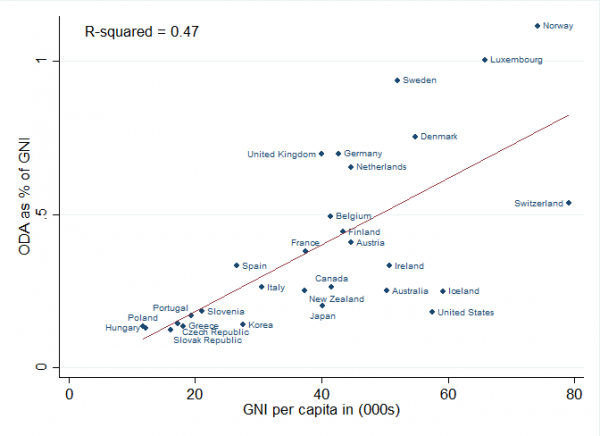

As this chart shows, there is indeed a surprisingly clear relationship between economic health, as measured by countries’ GNI and the share of their GNI that their governments give as aid. (All of the data in the following charts is for 2016.)

GNI and ODA/GNI

Unfortunately, the relationship doesn’t offer Australia or New Zealand any excuses for being miserly. The red line on the chart plots the average relationship between GNI and aid effort. Countries above are comparatively generous given the size of their GNI. Countries that are below the line are under-performers — and that’s where we find Australia and New Zealand. We aren’t as cashed-up as some countries. Yet we’re wealthy enough to be doing more. The only countries with a higher GNI than New Zealand that are less generous are Iceland, Japan and the United States. The only countries with a higher GNI than Australia that are less generous are Iceland and the United States.

As I started thinking of other possible excuses I latched onto another: The Debt. This seemed like a good contender. The political rationale for the 2015/16 aid cuts in Australia was the need to bring the deficit under control and in New Zealand the standard excuse for why we can’t give more is our fiscal ill-health. True, as far as excuses go, debts and deficits are tenuous ones. Aid is too small a share of government spending in Australia and New Zealand to actually make much difference. But let’s set such scepticism aside for a moment, and enjoy another chart, this one of the relationship between net debt as a share of GDP and ODA/GNI. Once again, it turns out that there is a strikingly clear relationship. More indebted countries are much less generous donors, on average. (There are slightly fewer dots than the chart above because IMF debt data was not available for all donors.)

Net Debt and ODA/GNI

Obviously, Norway’s an outlier — blessed with both oil and common sense. (Negative net debt being savings.) But, while removing it reduces the R-squared, even without Norway the slope of the line of best fit stays almost identical. And once again Australia and New Zealand are well below the line plotting the average relationship between debt and aid generosity. Almost all of the countries on the chart are more indebted than either Australia and New Zealand, and many are more generous donors. Indeed, no country with net debts as low as Australia and New Zealand’s gives less ODA as a share of GNI. (If you’re wondering whether matters would change if I looked at gross debt or deficits instead, I provide data for you to do the tests yourself in the next paragraph. But the short story is no — we look bad regardless of the measure you use.)

One final excuse is might be that our real issue is a combination of debt and comparative poverty, maybe we’re quite indebted and quite poor, and those factors taken together are a sufficient excuse for being tight-fisted.

Sadly the answer is no. When I run multiple regressions including both debt and GNI as predictors of aid effort at the same time, Australia and New Zealand still come out poorly. (To see the regression results, data, and information on where the data came from, download this spreadsheet.) With two independent variables it isn’t possible to show Australia and New Zealand’s comparative performance using a scatter plot. But the bar chart below conveys the message. It shows donors’ actual aid efforts compared to their predicted aid efforts based on the average relationship between GNI, debt and aid. Negative values mean a lower than average aid effort given indebtedness and GNI.

Expected versus actual aid effort on the basis of GNI and debt

Comparative poverty and indebtedness do seem to be associated with lower aid generosity amongst OECD donors. However, they give Australia and New Zealand no excuse. Our aid effort is much worse than it should be, even taking our economic situations into account.

Comparative poverty and indebtedness do seem to be associated with lower aid generosity amongst OECD donors. However, they give Australia and New Zealand no excuse. Our aid effort is much worse than it should be, even taking our economic situations into account.

Terence Wood is a Research Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

The idea of New Zealand increasing foreign aid spending under the existing frame work is insane! Throwing away tax payer dollars at a ill-defined goal (economic development) without better measurements of success is not a good idea. Merging aspects of the defence and foreign aid budgets would provide a way forward. Putting the infrastructure in place to put the PPP on a more sustainable/active basis would be a achievable/measurable goal.

Have you compared ODA as a % of central government spending across OECD countries? Would be interesting to see.

Look on the bright side Terence: President Trump would be pleased with us as we will soon meet our fair share of defence spending at 2.0% of GDP https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/minister/christopher-pyne/media-releases/budget-2017-18-defence-budget-overview.

Terence,

A terrific piece but very depressing. I am not surprised by the data but it is still depressing to read it. I agree that Australians are not overall selfish people but we need to improve the information flow to them about the real situation. This data might help.

Thanks Bob. I agree that the data don’t fit well with either country’s preferred narrative of itself. Definitely depressing.

Terry, so far you haven’t found the explanation. I whether you could explain Australia’s policy in relation to international aid.

Is it ignorance? greed? laziness? fear? Enlightened self-interest would entail a more generous policy, so from any perspective it seems difficult to understand.