Basic medicines are essential for an effective health service, yet Papua New Guinea’s health facilities typically go without drugs for half of the year. Why has the situation got so bad and what can be done?

In April this year, the PNG Department of Health announced that it has begun a serious effort to confront the dysfunction that has plagued the country’s medical supply system for a decade or more. Central to this reform are efforts to confront the reported widespread and entrenched corruption in the procurement and distribution of medical supplies in PNG. AusAID is supporting this effort.

This is a welcome initiative. Medical supplies are essential to the core infrastructure of an effective health service. Improvements to quality of service through training; supervision; innovation and partnership are almost nonsensical if basic inputs (including medical supplies) are not in place.

But reform will not be easy. A new Policy Brief from the Development Policy Centre on ‘Medical Supplies Reform in Papua New Guinea: Some conceptual and historical lessons’, draws on a number of conceptual and historical lessons to offer insights into factors which may facilitate or constrain the achievement of reform.

Conceptually, the Brief draws on the work of Lant Pritchett on the mechanics of “persistent implementation failure” and “capability traps”. This work–well summarised by Richard Curtain for the Development Policy blog–argues that there is a tendency for fragile, poor performing countries to “mimic” external organisations through the adoption of “best practice”, based on the assumption that function will follow form. Actors, imbued with an apparent “success” (a policy, an operating procedure, an increased budget allocation), and operating under a cloud of “wishful thinking”, ask too much, too soon of fragile organisations and implementation failure ensues. This phenomenon is described as “premature load bearing”. Pritchett et al argue that such failure becomes “persistent” due to a range of incentives that operate on both internal and external actors to keep searching for best practice, while measuring progress of inputs or outputs rather than outcomes, and not looking for alternatives. This can lead to a recurrent dynamic of failure and a “capability trap”.

The proposed way out of such situations is to create a space for organic change embedded in local context and capacity. Central to this strategy is a more strategic role for the state, and a constant focus on appropriate outcomes.

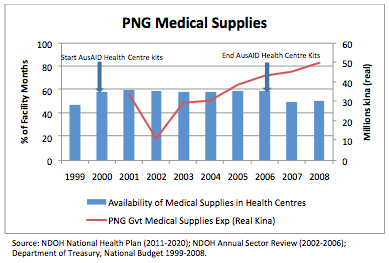

Despite increases in funding, availability of drugs has not improved. The Policy Brief presents historical data on the availability of medical supplies in PNG combined with Government expenditure and donor direct provision of medical supplies. This data is summarised in a graph showing the availability of basic essential medical supplies in PNG health centres from 1999 to 2008 (blue bars). Supplies increased in 2000 and decreased in 2006 in line with the timeline of a AusAID-supported program of direct (outside of Government) procurement and distribution of health centre medical supply kits. The graph also shows the reported increase in Government expenditure on medical supplies (red line) over the period to 2008 in real kina terms–a trend (not shown in the graph) which has continued in to the present.

Despite increases in funding, availability of drugs has not improved. The Policy Brief presents historical data on the availability of medical supplies in PNG combined with Government expenditure and donor direct provision of medical supplies. This data is summarised in a graph showing the availability of basic essential medical supplies in PNG health centres from 1999 to 2008 (blue bars). Supplies increased in 2000 and decreased in 2006 in line with the timeline of a AusAID-supported program of direct (outside of Government) procurement and distribution of health centre medical supply kits. The graph also shows the reported increase in Government expenditure on medical supplies (red line) over the period to 2008 in real kina terms–a trend (not shown in the graph) which has continued in to the present.

Viewing the data in this form provides a number of insights vis-à-vis medical supplies performance in PNG over the past decade. It also serves to highlight a number of the risks and opportunities to reform identified in the Pritchett analysis. Specifically:

- An external donor can successfully complement Government efforts in the provision of medical supplies and increase the availability of supplies throughout the country.

- The phenomenon of “premature load bearing” is real as witnessed by the decline in availability of medical supplies at the end of the donor program (back in fact to the level that existed prior to the commencement of the program). Clearly assumptions about enhanced capacity in this area were optimistic.

- The importance of maintaining focus on the key outcome of interest. In the above example, inputs in the form of increasing government expenditure did not translate into increased availability of medical supplies at a health centre level (despite there being declining utilisation during that period). Reforms need to be constantly tested and calibrated against observed performance.

Whatever else is wrong with the system of medical supplies in PNG, it is one area where we have reasonable data, on both inputs and outcomes, and more use should be made of it.

PNG efforts to reform its medical supply system are both critically important and incredibly complex. PNG reformers will need to be committed and courageous for an extended period of time, as will their external supporters. There is a strong conceptual and practical case for PNG’s donors to support this process through the direct provision of medical supplies. There will be pressures, both internal and external, to end external support prematurely. If the conceptual and historical lessons are to be beneficial, this pressure must be resisted.

Andrew McNee is a Visiting Fellow at the Development Policy Centre at the ANU’s Crawford School.

H.E.O student-DWU

I am doing a presentation on this Brief Policy Article today (Monday, 11/04/016) I would like to congratulate the author of the article, it was very useful.

I would like to know more about the types of external and internal factors that is meant to either facilitate or restrain the current reform system of PNG.

This is a welcome initiative. Medical supplies are essential to the core infrastructure of an effective health service. Improvements to quality of service through training; supervision; innovation and partnership are almost nonsensical if basic inputs (including medical supplies) are not in place.

The thrust of this policy brief is how do we (donor community and development partners) support and strengthening partner country systems, in this case the public health supply chain system. How do we respond to the issue of sustainability, which I would argue is both financial and operational sustainability. PNG may be increasing its financial sustainability (i.e. increased govt exp to procure medicines) but, its operational sustainability is weak (i.e. cannot maintain order fill rate improvements, inventory mgmt, etc.). A question would be for donor funding and, specifically, in PNG how did AusAID prioritize their funding? That is did it aim to (1) ensuring access & availability of commodities or (2) strengthening the system to function more effectively. These objectives are necessarily the same thing or mutually reinforcing.

Andrew McNee is to be commended for his insightful Policy Brief.

The procurement and distribution of medical supplies, medical equipment and other essential non-medical stores to and within PNG is one of the most complex and difficult supply chain tasks undertaken. The further strengthening of the PNG health supply chain will take time, resources, commitment and significant leadership.

I look forward to learning of the success of this new intervention.

This is a great report. The graph shows the supply of medical supplies to Area medical stores in Provinces and then to major distribution points to health facilities in provinces. However, it does not show what happens from then onwards. How should or does the supplies get to the remotes health facilities, eg Aipost in the remote areas of PNG? Who is responsible for this to happen? Is it the responsibility of the health worker at the aid post or other people who care for the health to the poor remote people?

Hi Dr Samiak

I am the Project Manager for our PNG PEPE Project and think I can help answer your questions. Medical supplies can get to remote health facilities in PNG in one of two ways. The first is through medical supply kits, where centrally funded contractors are responsible for distributing these kit sets to all health facilities across PNG. This includes even the most remote aid posts, as in recent years, the contractor would only get paid if they took a photo and obtained a GPS reading from the site where the kits were delivered. This is known as the ‘push’ system, as it should provide health facilities with their basic medical supplies.

The second way for getting drugs to remote health facilities is through Area Medical Stores. This is also known as the ‘pull’ system, whereby health facilities order drugs based on their requirements. Provinces are funded through the health function grant to pay for the costs of distributing ordered drugs from Area Medical Stores to health facilities. Often provincial and district health officials will have access to this funding as well as vehicles to assist with distribution, however some provinces allocate this funding directly to health centres who are then responsible for pick up and deliver of drugs to remote aid posts they may manage. I think it is fair to say that the ‘pull’ system requires significant strengthening to deliver medical supplies more reliably. This is why the medical kits are so important for remote health facilities.

Hope this helps to answer your question.

Colin