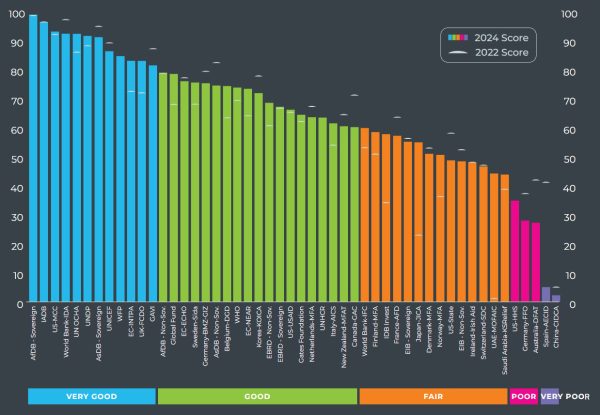

This week’s release of the 2024 Aid Transparency Index — compiled biennially by Publish What You Fund from the data contained in its International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) — puts the transparency of donors’ development cooperation programs in a comparative context. The results are not good for Australia. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), which delivers most of Australia’s aid, ranks 48 of 50 (poor) in the 2024 Index. This puts it below aid agencies in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and only two places above China’s International Development Cooperation Agency (very poor) which ranks last, just below Spain (also very poor) at 49th.(Figure 1). The highest-ranked bilateral agency is the US Millenium Challenge Corporation, which ranks third overall.

Figure 1: 2024 Aid Transparency Index ranking

Source: Publish What You Fund (2024), 2024 Aid Transparency Index

This is a decline from Australia’s performance in the 2022 index, when it ranked 41 of 50 (at the low end of fair). Indeed, 2024 is the first time since Australia began participating in IATI in 2012 that it has been scored as poor (see Figure 2). As in 2022, in 2024 DFAT ranks below all its donor agency peers: the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (10, very good), USAID (25, good), New Zealand’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) (30, good) and Global Affairs Canada (31, good). Australia’s fall in 2024 has been attributed to DFAT’s decision to “pause” reporting to IATI between 2019 and 2023.

It is important to note the limitations of the IATI data, limitations that other analysts have acknowledged. The data sets are complex and compare both multilateral and bilateral, as well as OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) and non-DAC donors, of which only some (Saudi Arabia, UAE) already report their aid to the OECD. There are also limitations when it comes to the quality, comparability and usability of the data.

And DFAT has made notable improvements over the last couple of years when it comes to the publication of aid budget information and information relating to aid performance and evaluation. In one important area, providing information on overall aid spending, DFAT still performs much better than New Zealand’s MFAT, which doesn’t even provide a basic total of annual aid spending. Yet New Zealand still ranks far above DFAT on Publish What You Fund’s index.

Nevertheless, Australia hasn’t ever scored above the “fair” in the Index. The consistent decline in relative performance since 2018 also mirrors the absolute decline which the Development Policy Centre has tracked through its own biennial Aid Transparency Audits over the last decade. The last audit, undertaken in 2022, called for an urgent “aid transparency reset” given worsening performance in the availability of all types of DFAT’s basic aid investment documentation. Just two years earlier, in 2020, the Morrison Coalition government committed to improving aid transparency by benchmarking DFAT’s progress against the methodology used in these audits, but aid transparency still fell.

As part of its 2023 International Development Policy, the Albanese Labor government has re-committed to a development program that is “transparent, effective and accountable”. DFAT resumed reporting to IATI in 2024 and, from 2025, will use Australia’s ranking in the Index as one of the indicators through which it will measure its progress on transparency, although it has not set a target. DFAT will also establish a new online development portal, which is due to be completed by the end of this year, which will include “financial and performance data, as well as key documentation on all DFAT managed ODA investments”.

This is all encouraging. But it is clear from both successive IATI reports and the Transparency Audits that the 2024 Index result is not a one-off result but rather indicative of systemic challenges that will require solutions that go behind the forthcoming portal. While the portal may be the technical mechanism through which aid transparency will be improved, it will only be as good as the incentives, oversight and resourcing that sit behind it. Indeed, a potentially worse outcome than the status quo would be the launch of an online portal that degrades over time because it is either not regularly updated or not adequately resourced. As anyone who works in development knows, governance, the alignment of incentives and resourcing are at least as important as technical solutions.

In our submission to the 2023 policy process, one proposal that Terence Wood and I put forward is that DFAT adopt a Transparency Charter, as was previously in place for Australia’s aid program. The Charter, which would sit behind the new portal, could set out why aid transparency is important in terms of both accountability and learning, identify the specific types of information that will be published, and define the expectations and roles of staff and senior managers, including the new “senior responsible officer” positions now being created at posts.

Implementation of the Charter and oversight of the supporting portal could be overseen by DFAT’s Development Program Committee, chaired at Deputy Secretary level, which would receive regular reporting on implementation, patterns of uploads and use, and adjudicate on any applications for exemptions from publication on the basis of confidentiality or other specified grounds. The Committee could also regularly publish an internal transparency scorecard. Resourcing would be provided through the quarantining of funding and specialised staff to progress the transparency agenda as part of DFAT’s stated ambition to improve development capability and accountability.

The Minister for International Development and the Pacific, Pat Conroy, has repeatedly said that transparency is one of the five defining features of the current government’s approach to Australia’s development assistance. While there has been some progress since 2022, the urgency of a transparency reset remains and, as Publish What You Fund’s 2024 index illustrates, there is still much to do.

Disclosure

This research was undertaken with the support of the Gates Foundation. The views are those of the author only.

Leave a Comment