I was in the midst of a Monday afternoon recently when a flurry of agitated emails barged into my inbox. Their subject? The submission World Vision had made to the Australian government’s consultation on its new development policy.

When I got round to reading it, I actually found some parts of the submission very reasonable. There was concern about climate change. The call to rebuild DFAT’s aid capacity was spot on. And the case made for more people-focused development and less infrastructure spending was sensible.

If the submission had stuck to these types of arguments, I doubt a single email would have been written about it. But it didn’t, and right from the start it was obvious what had everyone angrily hitting the send button: a full-frontal attack on Australian aid to United Nations organisations and multilateral aid in general.

I’ve interacted with World Vision staff in the past. They’ve always been thoughtful and insightful. In places, however, the submission reads like it was written by an unrepentant Iraq-war-era neoconservative trying to settle scores with Kofi Annan. At one point UN agencies are referred to as a “black hole”. At another, the submission demands that the “spray and pray” approach of giving aid to the UN come to an end. Aid to multilaterals, it claims, has caused “Brand Australia” to “nosedive”.

The rhetoric alone nearly made me stop reading. But I struggled on. As I did so, my next source of frustration was the conflation of the UN and multilateral organisations more broadly. Much of the actual critique in the submission is focused on the UN. However, all of its numbers pertain to Australia’s multilateral aid as a whole.

So we are told on the cover page that “Almost half of Australia’s aid is currently directed to global multilaterals like the UN” . Then on page 1, “Australia delivers 43 per cent of its aid budget through the UN and multilateral agencies”. And later on the same page, that “almost half of our aid budget [goes] to the UN”.

I’m sure I don’t have to explain this to a Devpolicy Blog reader, but there are, depending on how you count, about 186 aid-eligible multilateral organisations according to the OECD. Only around 66 of those are UN agencies, funds or commissions.

It’s easy enough to learn which multilateral organisations Australia gives aid to from OECD reporting. So I downloaded data for Australia and took the average of the five most recent years with full data (2017-2021). Across those years only 38% of Australian multilateral ODA (official development assistance) went to UN organisations. More than 45% went to the World Bank and regional development banks like the ADB (Asian Development Bank). (Strictly speaking, the World Bank is part of the broader UN system, but its governance, mandate and operation are completely different from the UN’s development agencies.)

The distinction between “UN” and “multilateral” matters. Organisations like the World Bank, GAVI (the Vaccine Alliance) and ADB differ a lot from UN entities like UNDP, WHO and the World Food Programme. They play different roles, they operate differently, and their efficacy varies. Producing numbers that conflate “multilateral” and the “UN” obscures a lot.

The next issue was the submission’s claims about multilateral aid going into a transparency “black hole”. Based on OECD CRS (common reporting standard) data, on average from 2017 to 2021, slightly more than half of Australian aid to multilateral organisations was tied to specific projects. This aid is every bit as transparent as Australia’s bilateral aid, including its aid to NGOs. You can get detailed project information on DFAT’s website for some of it. And you can get basic project details for almost all of it from Australia’s OECD reporting.

Most major multilateral organisations, including big UN ones like UNDP, also provide project-level data on their own work to the OECD. This doesn’t tell you where each Australian dollar goes, but it does give you a good idea of the work these multilaterals do. And while Publish What You Fund’s aid transparency index has its flaws, it allows a useful sense of broader transparency across organisations. In 2022 the best scoring organisations on the index were almost all multilateral agencies. Australia was well down the list.

Some multilateral organisations could be more transparent. But that’s true of almost all donors, including Australia. Transparency isn’t solely a multilateral organisation or UN problem. And Australian aid flowing to multilateral organisations isn’t vanishing without a trace.

Finally, there were the submission’s claims that UN/multilateral organisations were less effective. There’s a good discussion to be had about which types of multilateral organisations are most effective, and whether or not it is worth continuing to engage with less effective ones. (World Vision itself partners with the World Food Programme, so I presume they don’t think all UN agencies are irredeemable.) However, none of this discussion was in the submission. Rather, there were statements like this: “Funds going into the ‘black hole’ of UN agencies are rated the lowest of the three Partner Performance Assessment (PPA) ratings undertaken on NGOs, multilaterals like the UN, and contractors…”

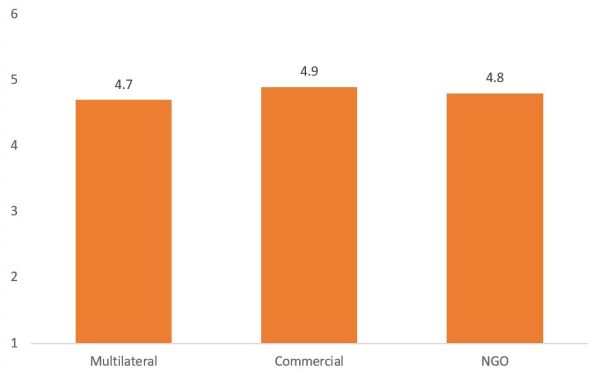

The most recent DFAT partner performance data that I can find disaggregated by partner type comes from this 2018-19 report. (The numbers in the chart below come from page 8.)

Average DFAT partner performance by organisation type (2018-19)

NGOs score 0.1 better than multilaterals on a 1-6 scale (2% better in other words). The difference is so small that given sampling and the vagaries of subjective assessments it provides no basis for confident claims that multilaterals are worse.

Multilateral organisations have their strengths and weaknesses. But they are not a homogeneous group. And they aren’t all the UN. On average, NGOs don’t obviously outperform them in delivering Australian aid either.

Those are the basic facts. But you won’t learn any of them from World Vision’s submission. I can see why people were emailing angrily.

Disclosure

This research was undertaken with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The views are those of the author only.

So Terence, no response from WV yet?

No response that I’m aware of (I don’t run the blog). But, to be fair to them, these sorts of debates may be the sort of thing they don’t want to get entangled in. Most of their work is aid practice, after all.

This is an important issue for analysis and discussion, not only for Australia and the beneficiaries of its development assistance, but also across the world, as the ‘development suport’ industry is substantial, entailing large numbers of government, multilateral, NGO participants and employees, but many commercial, or semi-commercial management contractors, academics and others, ie it’s big business, and includes participants (firms and individuals) on substantial packages, as well as volunteers and local staff on hugely contrasted conditions in the developing countries. There are huge overheads, entailing often duplicative responsibilities in Departments, such as DFAT, and the managing contractors and the Multilateral and international NGOs, and some private managing contractors, like UN agencies, can be seen as operating in an increasingly uncompetitive global environment, as bigger firms buys out big ones.

There is also a considerable variation in the relevance as well as the performance of projects and programs managed by development partners and agencies, not just between agencies, but also within their own portfolios. At the moment in PNG we’re in the midst of a self-belief exercise by many agencies, including DFAT,UN, but also World bank and others. There’s a tendency of staff to be somewhat self-commending, or at least uncritical, but it’s good to see some current reviews being somewhat more analytical. Hopefully, such hard reflection and discussion will result in meaningful change, better focus, trimmed costs,more coordination and cooperation, and less duplication, learning lessons from each other’s mistakes, and not just one’s own.

The old days in PNG when nearly all public sector work was conducted by respective PNG Govt agencies, even where development partners cofounded, whether GoA, through Budget aid until about 1990, as well as WB and other financing, was much more cost effective, with far less of the project and administrative costs, and tax exempt conditions. There was also much greater use of professional international volunteers, rather than consultants. Unfortunately, as GoPNG institutions were increasingly politicised, subject to crony appointments and largest ( in the form of constituency funds etc) it became harder for development partners to justify funding being channelled through such vehicles. Nevertheless, restoring more cost effective local institutions, both governmental and non-governmental ( including services delivered by FBOs) should be an objective, including in supporting demand driven mechanisms, which in the end enable more accountable and sustainable local public financing. Engaging reinforcing local non government organisations, which are have their strengths as well as weaknesses, is also critical, and they’re certainly more cost-effective than both the multilateral and international NGOs, but too often ignored or gaining only the crumbs from the high table…

Indeed, the lack of precision in terms of how ODA is discussed within the Pacific is somewhat depressing. It is as pointless to aggregate all multilaterals as it is to aggregate all INGOs or indeed all NGOs and CSOs.

There is a strong case by case argument for the abject failure of many of the IFI interventions in the region as there is for many INGO interventions. However, INGOs are a relatively recent addition to the Pacific ODA scene for most countries and hence there are not as many examples of total intervention failure due only to the fact that they have not really been around that long.

In the Pacific the issue is made more complex because almost all INGOs are essentially Managing Contractors i.e. their income is derived from bidding for projects as opposed to charitable donations. So technically they are not actually even INGOs but rather Not For Profit Private Sector Entities. This is important to understand from a regulatory point of view – so for example their performance should be measured against other MCs as opposed to CSO’s for most cases.

Thank you Paul and Nik,

Good interesting comments. Sorry, I’m travelling so can’t engage more right now.

Nik, one thing I’ll note though, is that, particularly for humanitarian work, some NGO funding for Pacific work does come from donations. The phenomenon you describe is real, but is not the whole story.

Terence