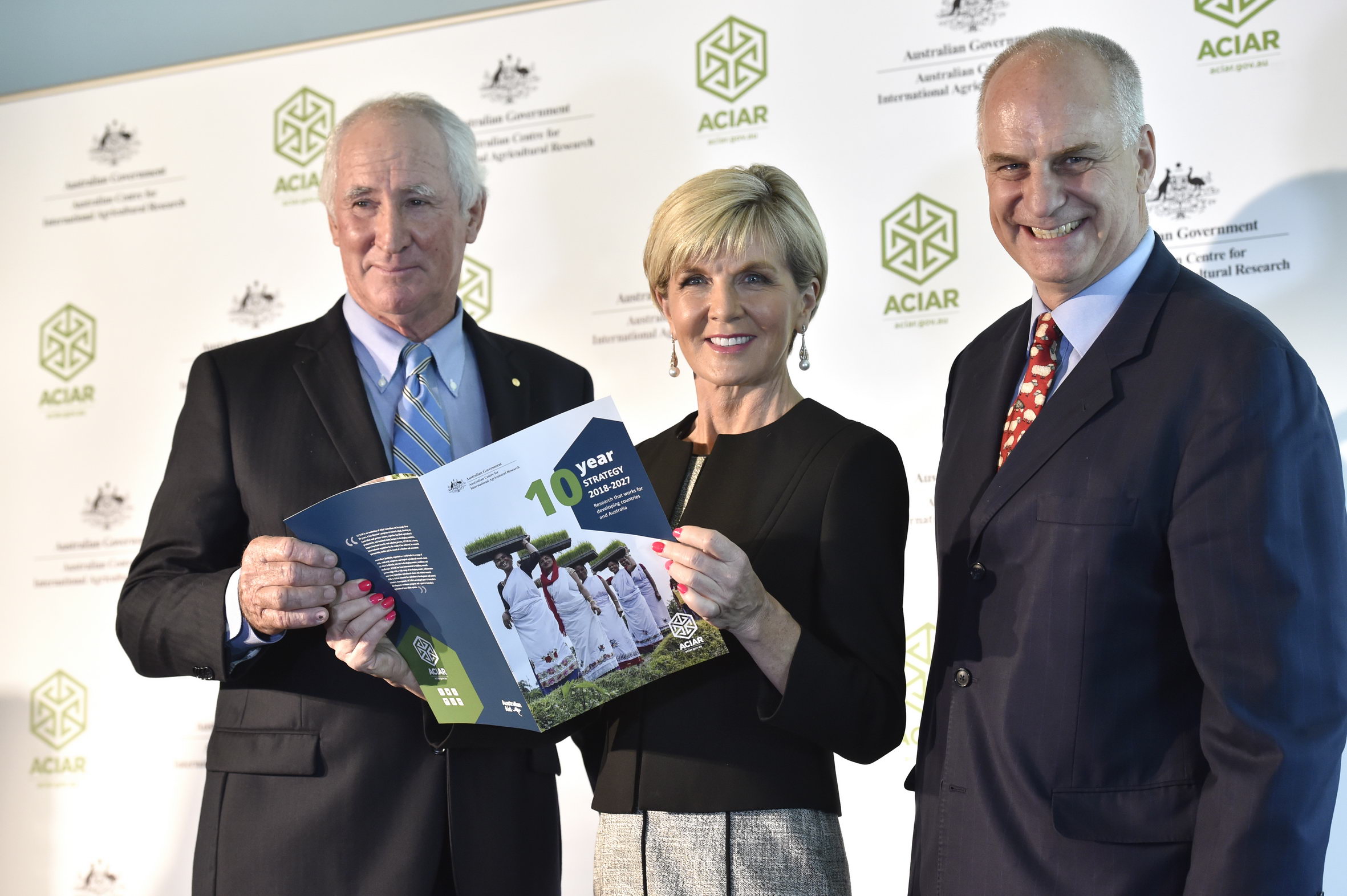

Last week, Foreign Minister Julie Bishop launched a new 10-year strategy for the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), describing ACIAR as a ‘quiet achiever’ within the Foreign Affairs portfolio.

ACIAR has been brokering and funding research partnerships in the Indo-Pacific region since 1982. Recognising that Australian agricultural, fisheries and forestry science has much to offer the world, the Fraser Government, on the advice of Sir John Crawford and others, established ACIAR as an independent statutory authority within the Foreign Affairs portfolio, reporting to the Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Over the last 18 months, it’s been obvious to me — as just its sixth CEO — that the people who conceived and established ACIAR got many things right. My predecessors developed and refined a very effective business model based on collaborative prioritisation of research with partner countries, astute commissioning of expertise from mostly Australian research providers, and hands-on management of research programs by experienced ACIAR program managers. They imbued the organisation with a distinctive combination of good applied science skills and a deep understanding of smallholder agriculture, fisheries and forestry in the Indo-Pacific region.

The ACIAR Act also mandates us to strengthen research and policy capabilities within partner countries, by funding postgraduate and professional scholarships linked to ACIAR programs, and masterclasses through the Crawford Fund. Many of our alumni are now leaders in the region.

Unfortunately, the need for well-targeted and well-managed research to improve the knowledge base for improving food security is more compelling today than ever. Moreover, the challenge of feeding humanity is no longer just about increasing agricultural production. Food security is also about access, distribution, safety, health, and nutrition.

The number of people suffering from acute hunger worldwide appears to be rising again, to over 800 million, after a promising downward trend over the last decade. Around two billion people suffer from micronutrient deficiencies, many with lifelong impacts. More than two billion people are overweight or obese, with profound associated health problems, through non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and heart disease.

Hunger, micronutrient deficiency, and obesity represent the so-called ‘triple burden’ of food insecurity.

The evidence is clear: lifting agricultural productivity in ways that help female and male smallholders to access higher value markets is among the most effective forms of international development for reducing poverty and catalysing economic growth.

While the global aggregate food supply has kept up with population growth over recent decades, there is no room for complacency. The FAO estimates that we need to increase overall food production by around 50% by 2050. As productivity growth is flattening in the major staple crops, this is a big task. Moreover, the need is not evenly distributed: Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia need to lift production by around 112% by 2050, compared with an average of 34% for the rest of the world.

However, food security cannot be considered in isolation from water security, energy security or biosecurity.

These ‘converging insecurities’ are all amplified by climate change, the ultimate risk multiplier.

The challenge is to grow healthier food and more of it. We must distribute and share it better and waste less. We will have to do so in more difficult climates and in a decarbonising economy, using less land, water, and energy, and fewer nutrients.

This is among the most formidable scientific, policy and political challenges of our age. Australia has the expertise to play a leading role in tackling it.

Our most important agricultural export is between our ears. It’s our know-how — hard won on an ancient continent, weathered by the world’s most variable climate, and leached of its nutrients over aeons.

ACIAR’s new 10-year strategy aims to make us a more effective investor and broker in tackling these multifaceted challenges, while keeping the best of ACIAR.

Human nutrition and health, managing natural resources more sustainably, mitigating and adapting to climate change, empowering women and girls, and working more effectively with the private sector are now high-level objectives for ACIAR. They sit alongside our traditional goals of food security and poverty reduction.

This more integrated outlook is at the heart of the strategy, which also foreshadows:

- A greater emphasis on outreach, to better promote research findings and showcase impacts and benefits.

- Refocused investment in capacity-building to train more scientists from developing countries, transform their leadership and management skills, and to stay in closer touch with our alumni.

- Building on traditional strengths in project-level impact assessment to improve portfolio-level evaluation.

- The establishment of a Chief Scientist position and new Associate Research Program Managers in cross-cutting areas like nutrition, gender and climate.

These measures are designed to respond to more complex, intersecting issues more effectively, and help us to build on ACIAR’s reputation as a learning organisation – a ‘keeper of the long view’.

For some research disciplines and some agricultural commodities, ACIAR is the largest Australian source of research funding. ACIAR projects are seminal in the career development of many scientists. We will work more strategically with universities, CSIRO, and others to help build the scientific capabilities that Australia needs to address the converging insecurities more effectively.

The strategy allocates more resources for co-investment with larger donors, as we are already doing with our Canadian counterpart the IDRC, and private sector partners.

Our most important co-investor, however, remains the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. We will work even more closely with DFAT – in our diplomatic missions; in aid investment planning and evaluation; through the Australia Awards, the New Colombo Plan and volunteer programs; and with specialist units such as the innovationXchange and the Indo-Pacific Centre for Health Security.

It is crucial that aid investments are built on good science and durable partnerships. Equally, we need development funding to help take ACIAR innovations to scale. The ACIAR-DFAT relationship is ideally synergistic, and there are many excellent examples where DFAT development work has extended ACIAR-funded science.

Our challenge through the new strategy is to design more ‘joined up’ long-term investments to address the ‘triple burden’, over which ACIAR’s role changes from research for development, to research in development.

The 2013 Independent Review of ACIAR described it as a unique institution at the intersection of Australia’s innovation system and its diplomatic outreach, of which Australians can be rightly proud.

This new long-term strategy lifts our gaze.

We want to consolidate ACIAR as a trusted science partner in the region and continue to build the knowledge base on which to tackle the most formidable challenges of our time.

Thanks Rod

ACIAR has always enjoyed strong bipartisan support and we are working hard on increasing awareness of our work to ensure that this continues to be the case.

Thanks Andrew, for a good reminder of the importance of agricultural research in the aid program. And, congratulations on the 10-year strategy. A 10-year planning horizon is responsible – and it would be great to see more of this in the aid program. Having bipartisan support would be even better.