The 2016 PNG Regulation covering non-citizen technical advisers (discussed in our earlier post on the subject) seems to have primarily resulted from a desire within the PNG Government to exert its national sovereignty. Under it, foreign government employees can only be engaged on a short-term basis under an Institutional Partnership Arrangement. PNG’s sovereignty has also been enhanced by the new requirement that the Agency Secretary give final approval for the engagement of a non-citizen technical adviser and sign a performance contract with that adviser. The requirement that the Secretary of PNG’s Department of Personnel Management keep a register of all non-citizen technical advisers also reflects PNG’s desire to increase its control over the engagement of non-citizens in its public service.

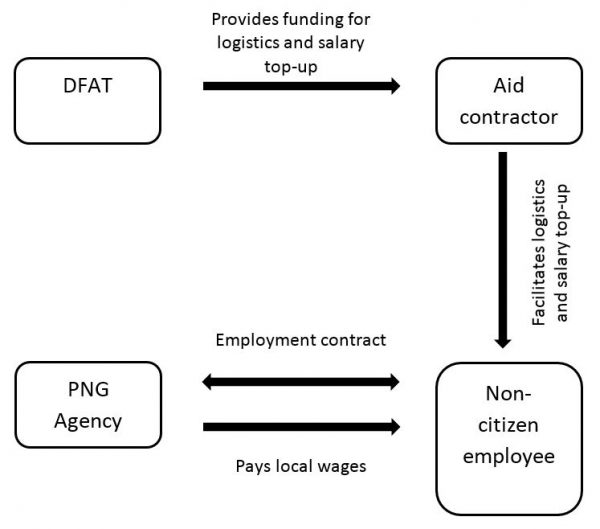

PNG and its development partners should consider further reform in this space. We hold the view that non-citizen technical advisers who are embedded in the PNG public service should be employed by the PNG Government, not by a contractor. In this scenario, aid contractors would coordinate the logistics but not act as the employer of these advisers (see Figure 1). The benefits of this approach are greater accountability and greater scope for aid funded non-citizens to be engaged in in-line positions and not just as advisers.

This proposed model is consistent with the Joint Review of Technical Adviser Positions in 2010 that recommended greater use of in-line officers that are contracted directly to the PNG Government who have full delegations of public servants, are accountable to the PNG Government and undertake the full functions of the role with the additional component of capacity building.

Figure 1: Proposed model for engagement of aid-funded non-citizens

The fundamental difference between this proposed model and the currently existing non-citizen technical adviser model is the recognition that the PNG Agency is the employer of the non-citizen. In our view, this reflects the reality of the engagement of many non-citizen technical advisers on the ground in PNG. It makes little sense to have an adviser, who works on a daily basis in a PNG Agency and reports to the PNG Agency Head, to be employed by a commercial aid contractor. As indicated above, this mode is compatible with and will promote the use of the engagement of non-citizen advisers in in-line roles.

PNG already engages many non-citizens in-line under the Public Employment (Non-Citizens) Act 1978. In these instances, the PNG Government is the employer of the non-citizens and is responsible for all costs associated with the adviser.

A model for co-funded positions also already exists in PNG with the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Fellowship Scheme. The PNG Government can make a request to ODI for staff with specific economic skills. ODI Fellows work as local civil servants for a period of two years, with the cost being shared between the PNG Government and ODI. Under the ODI model, the PNG Government as the employer is responsible for paying a salary equivalent to what would be payable to a locally recruited national with similar qualification and experience; providing conditions of service such as accommodation and leave entitlements similar to those offered to local staff in similar grades; and ensuring fellows receive assistance in obtaining work permits and security clearances where required. ODI on the other hand is responsible for selecting fellows, arranging placements; providing a pre-departure briefing and allowances; paying a monthly supplement; providing medical insurance; and paying an end-of-fellowship bonus.

Under the ODI model non-citizens are employed by the PNG Government and work in in-line positions, allowing them to make decisions and supervise staff, without the PNG Government having to bear the full costs. Non-citizens are employed in approved, funded, vacant, established positions and are subject to the same public service laws and standards as their PNG colleagues. By incorporating them into the establishment and by paying them their base salaries, the PNG agencies take ownership of their non-citizen employees. Non-citizens occupying in-line positions cannot be referred to as advisers but can be called non-citizen employees.

ODI Fellows represent a very small component of the adviser program in PNG – there are currently only four ODI Fellows working for PNG Agencies. But the ODI model could and should be used and adopted by other donors including DFAT. The role of aid contractors would be restricted to arranging the logistics (accommodation, health insurance, transport and security), and the payment of salary top-ups. DFAT would continue to be the source of the majority of the funding. The top-up of salary and payment for logistics by DFAT reflects the reality that this is necessary to both attract and retain non-citizen employees.

The adoption of a new model for non-citizen technical advisers (or employees) would need to be supported by legislative and regulatory reform. At the very least, PNG will have to review and update the Public Employment (Non-Citizens) Act 1978 which has remained largely unchanged since it was brought into operation shortly after independence. Similarly, the PNG Public Service General Orders do not provide adequate guidelines for the in-line engagement of non-citizens, particularly as they relate to advisers who are co-funded by contractors as part of an aid program. Lastly, there are a range of other matters (including important taxation issues) which will require careful consideration by both PNG and Australia before a new model for advisers can be introduced. But all of these obstacles can be overcome; all that is required is commitment from both parties to embrace a new way to engage non-citizens in PNG Government Agencies.

Joachim Luma is the Manager Executive and Legislative Reform Branch with the Department of Personnel Management during the development of the new Regulation. Michael Anderson was a non-citizen technical adviser to the Department of Personnel Management during the development of the new Regulation. Carmen Voigt-Graf is a Fellow at the Development Policy Centre.

This is the second post in a two-part series; read the first post here. Both posts are based on an Issues Paper recently released at the PNG National Research Institute.

Having worked in a mix of advisor/inline posts in a number of small island developing countries, funded by different development partners, around the world, I fully recognize the issues raised in the paper and the comments. They apply just as much in those situations. Working to develop greater clarity on roles and relationships is important.

Historically, UK used to have a clearer distinction between advisors, and inline funded positions, aka Overseas Staffing Assistance Schemes (OSAS). OSAS staff covered a wide range of posts including teachers, doctors, lawyer, engineering, other senior technical/managerial posts, even heads of ministries/departments. Australian also used to have an Australian Staffing Assistance Scheme (ASAS).

Currently both Australia and NZ have funded senior inline positions, such as Judges and Police Commissioners e.g. in Tonga. A review of the lessons from these historical systems (if sufficient people can still be found to give valid assessments of them) as well as assessment of current operations would help inform specifically the PNG situation and more generally the situation in many other countries facing the same issues.

BTW: current aid funded inline posts in the Pacific are not just filled by Australian or NZ citizens but also by citizens from one Pacific Island Country (PIC) working in another. This helps to increase experience and opportunities for qualified staff from PICs and helps to contribute to the development of a greater pool of skilled workers in the Pacific which can begin to help address the diseconomies of scale faced by PICS’ small labour markets.

i agree with Paul’s comments (disclosure: he was my Team Leader for most of thr time that i worked as an adviser in PNG Treasury). here are a few additional thoughts:

1. The ODI program is an imperfect model to draw partly because it is so remarkable: I’m not aware of any other similar program that draws such a consistently high calibre of candidates. So it may be difficult to replicate.

It is imperfect in other ways. It tends to place one or at most two individuals into an organisation when any chance of achieving sustainable systemic change in the organisation requires a team of advisers to help identify shortfalls in capability and support management to address them. (For example, addressing internal siloes, performance management, or recruitment.)

Finally, a team of advisers helps to moderate the idiosyncrasies that any one adviser may bring to a typically challenging, diverse role.

2. I agree that there is virtue in having some in-line roles but, as Paul suggests, there is a tension here: it is very hard to achieve the same emphasis on capability development once an officer is in-line. Being constrained as an “adviser” can act as an important discipline to work through local colleagues although it can, of course, also be an unhelpful limitation. (Getting the right balance between advising and doing was something I grappled with throughout my 3 year posting and discussed further in a 2014 paper i co-authored on Capacity Development in Economic Policy Agencies.)

3. Finally, there is the very difficult question of what to do when a Departmental Secretary may be engaged in corruption (several have been subject to corruption allegations in recent years). It places the adviser (and DFAT) in an invidious position if the adviser is solely responsible to such a person. This is also a problem for advisers but the problem is not quite as acute when the person is not your boss.

Hi Paul and Harry,

Thank you for the positive feedback on our paper and blogs.

We agree with your comment that it is difficult to get the right balance between the (sometimes competing) sovereignty interests of the host country and the development partner when it comes to the placement of non-citizen TAs. The events in PNG in 2016 which led to the departure of some SGP advisers certainly highlighted this tension.

Our model suggests PNG is the employer of the TA. It doesn’t seem appropriate or logical to us that the adviser is employed by a third party contractor when in reality they work within the PNG public service. As you point out, advisers can have access to all sorts of information about government business/interests which can often be of a confidential nature. A lot of the frustration from the PNG side in 2016 centered around the fact that there was essentially no legal relationship between the various Australian advisers embedded in the public service and their Agency head. We think the new requirement to sign a performance contract (PCA) only goes a part of the way and the best model should recognise PNG as the employer. This approach shows appropriate respect for PNGs sovereignty.

Having said that, you make the very valid point that TAs are ultimately funded by the Australian taxpayer. We agree with your observation that there should be appropriate accountability back to DFAT to ensure taxpayers resources are being spent wisely. It is perfectly legitimate for Australia (or any other development partner) to have this expectation. We think a model where aid-funded TAs are employed by PNG can still have appropriate monitoring and accountability mechanisms, including via the contractor who is retained to provide the logistics and other support.

We also accept this couldn’t happen overnight primarily because there is no regulatory framework in PNG to accomodate it. At the very least we hoped to generate some discussion and thought through the NRI piece and the blogs.

Thanks again for your comments,

Michael, Joachim and Carmen

Hi Joachim, Michael and Carmen

Thanks for this analysis. Some interesting background and thoughts on this previously very important element of the PNG Australia relationship.

Three quick thoughts.

First, I agree strongly with Michael’s “A Personal Account” in the NRI paper which states “I had no issue signing the new performance and Conduct Agreement and the Code of Conduct. In fact, the PCA just confirmed what was already happening in my placement. All of the other technical advisers I have spoken to were also happy to sign it, recognising that it did not change their current working arrangements (page 9).” This reflects my own experiences as a Team Leader under the Strongim Gavman Program from 2011 to 2013. Good advisors knew they were working for the PNG government and doing otherwise risked one’s acceptance in any PNG team and hence overall effectiveness.

Second, one of the issues for the previous aid adviser review was the issue of accountability. This includes accountability linkages to Australian taxpayers for the effective expenditure of TA advisors. A major issue with the suggested model is that there is no arrow with a clear accountability linkage back to the box marked “DFAT” which is of course the proxy for accountability on the performance of aid expenditure. This is a difficult linkage to put in place in a way that respects the sovereignty and rights of both countries. I do remember getting in trouble with DFAT under the old framework for indicating that I had examples of where advisors had worked effectively as part of a PNG team to produce major development gains for PNG – but I couldn’t be specific given the requirements of PNG cabinet confidentiality.

Finally, it could have been useful for the paper to use some broader background material other than the 2010 aid adviser review and PNG government comments. After 2010, there has been quite an active discussion, including on this blog, on different views about the effectiveness of technical advisers and governance in PNG – for example a 2012 effectiveness review of the SGP program (see https://devpolicy.org/strongim-gavman-program-in-png-reviewed-20121213/). There are some nuances around “in-line” positions and the lessons which moved the former ECP program towards the more capacity orientated SGP program should not be forgotten. My view is that institutional linkages programs were extremely effective (for example, see my presentation to the 2016 Aid Conference at https://devpolicy.org/2016-Australasian-aid-conference/Presentations/Day-1/2b-Australia-PNG-and-Fiji_Flanagan.pdf). So I agree entirely with Bob McMullan’s and Robin Davies recent blog on 21 April that an “easy piece” for addressing a gap in Australia’s aid program is “Public policies and institutions, through the re-establishment of a mechanism to support Australian public sector assistance to public institutions in the developing countries of our region.” PNG is losing out quite badly from the fake “spies” allegations from its Prime Minister which led to the closure of much of the SGP program. Many elements of PNG’s poor economic management in recent years (at least the loss of confidence flowing from major technical errors) are probably linked to the reliance on other very well paid foreign economic advisors working directly in the Prime Minister’s Office rather than a program of institutional support which has a number of in-built checks and balances.

Cheers

Paul Flanagan

PNG Economics and former SGP adviser