Last year we compared ten years of budgetary allocations and spending on PNG’s anti-corruption agencies. We found significant and growing gaps between what the PNG government promised to anti-corruption agencies and what they actually received. In this blog we draw upon updated analysis, including the recently released 2018 budget figures, to show how the state’s anti-corruption agencies have fared under Treasurer Charles Abel’s first budget.

Our analysis focuses on five key anti-corruption agencies: the Ombudsman Commission, the National Fraud and Anti-corruption Directorate, Taskforce Sweep (and its replacement: the proposed Independent Commission Against Corruption), the Auditor-General’s Office, and the Financial Analysis and Supervision Unit (also known as the Financial Intelligence Unit).

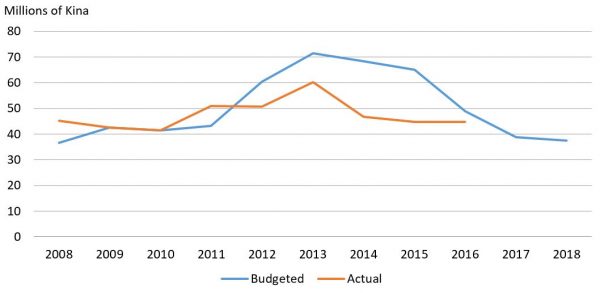

Overall, spending on the five anti-corruption organisations was essentially the same between 2015 and 2016 – adjusting for inflation, the government spent almost 45 million kina (or 17.7 million AUD) on these organisations in each year (see Figure 1). However, amidst broader budget cuts, future spending on these organisations is set to fall to below 38 million kina by 2018. Steady spending, along with shrinking budgets means that the gap between promises and reality has almost closed (though of course actuals may fall further). That’s one, although certainly not the best, way to reduce a funding gap.

Figure 1: Total anti-corruption spending for five anti-corruption agencies (2017 prices)

As we demonstrate, all five organisations except for the Ombudsman Commission have had their budgets cut between 2017 and 2018. The National Fraud and Corruption Directorate, which has unsuccessfully tried to enforce an arrest warrant on the Prime Minister, will see the biggest percentage cut: its budget has been more than halved during this period. Even the bump to the Ombudsman Commission won’t make up for a recent history of budget cuts. After cutting almost 3 million kina from the Ombudsman Commission’s budget between 2016 and 2017, in 2018 the government plans to increase the organisation’s budget by a paltry half-a-million kina. All this cutting means that by 2018, spending on these five anti-corruption organisations will make up less than 0.3 per cent of the national budget for the first time in the past decade.

Cuts to anti-corruption agencies are being made amidst budgetary reductions to other law and justice sector organisations. While the police received almost 70 million kina more than their budgeted allocation in 2016, the next two years will see massive budget reductions. Between 2016 and 2018 the police budget will be cut by 133 million kina, or a staggering 35 per cent. Almost 40 million kina, or 22 per cent, will be taken out of the Attorney-General’s budget over the same period.

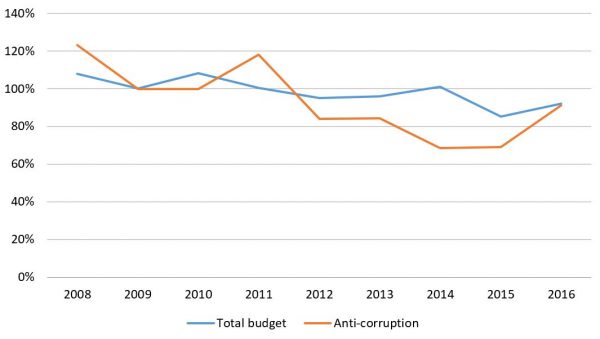

Our previous analysis showed that the gap between spending and budgetary allocations impacted anti-corruption organisations more than other areas of the budget. However, with the PNG government continuing to underpay a variety of government departments and programs, the gap has closed. Figure 2 shows that in 2016, 91 Teoa out of every kina (or 91 per cent) reached government departments, the same amount reaching the state’s anti-corruption agencies. This is an improvement on 2015 – a particularly bad year for converting budgetary allocations into funding – however, it highlights that the government has continued to starve many departments and programs of cash.

Figure 2: Actual spending verses budget spending for the whole budget and anti-corruption organisations

Amidst these budget cuts and underpayment the government continues to promote its ‘commitment’ to addressing corruption. This commitment is being met by amending and passing laws, rather than spending on anti-corruption bodies. The government has commissioned the Constitutional and Law Reform Commission (CLRC) to design laws for the new ICAC, and the CLRC is reviewing [pdf] the Organic Law on the Ombudsman Commission and the Organic Law on the Duties and Responsibilities of Leadership. The 2018 budget states that the government will aim to introduce specific bribery offences to minimise fraud and corruption; it also promotes the passing of anti-money laundering and counter terrorism financing laws, as well as amendments to the Proceeds of Crime, Criminal Code and Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters legislations.

However, the disparity between this legislative rhetoric and material outcomes is startling. In 2018, the budget for the country’s much-promoted ICAC is only 500,000 kina, half of its 2017 allocation (by comparison the Ombudsman Commission was allocated 19 million kina in 2018).

If one looks at the 2018 budget hard enough it is possible to make out a dim silver lining. The budget reveals that in 2016 the government spent close to four million kina on the country’s Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) – a global standard designed to improve transparency and accountability in extractive industries. The government intends to spend 2.7 and 2.6 million kina on the EITI in 2017 and 2018 respectively. As we show, when we add this to funding for the five anti-corruption organisations, it is not enough to halt the downward trend in budgeted anti-corruption spending, but it does help further close the gap between 2016 spending and allocations.

PNG’s engagement with the EITI shows that a mix of external and internal pressure can help focus the government’s meagre resources into improving transparency and accountability. PNG has been a member of the EITI since 2014. It has established the PNG EITI Multi-Stakeholder Group, which provides guidance and oversight on the EITI implementation process. In late 2017, the PNG EITI 2016 financial year report was released, and has already caused a stir by noting that the Bank of PNG has failed to produce receipts for oil and gas levy and royalty payments worth 73 million kina. While previous EITI reports have been criticised, the country is still much further along the EITI process than Australia, which is not yet a member, although in 2016 it announced its intention to apply.

The dim light provided by the EITI does little, however, to change the broader sorry story of PNG’s anti-corruption organisations.

As the PNG government faces a fiscal crisis, it is not surprising that anti-corruption agencies have taken a hit. At the same time, the government is keen to promote its anti-corruption credentials. This means that in the years to come we can expect the PNG government to focus on cost neutral measures: such as passing and amending laws that anti-corruption agencies do not have the resources to implement.

This research is a part of the Strengthening State and Society Responses to Corruption in Papua New Guinea project, which involves the Development Policy Centre and the Developmental Leadership Program. Calculations for graphs and tables can be found here.

Leave a Comment